Book Review: 1948 by Benny Morris

Content warning: war, Israel/Palestine conflict

Potential bias warning: I am a Jewish Israeli

My copy of 1948 arrived in late September, but I was in the middle of another book. Then October the 7th happened, and with the horrors of that day fresh in my mind, and my country in a brutal war, I wasn’t in a mental state where I could read about all the cruelties of another war between Israelis and Palestinians.

But ultimately I couldn’t abandon it. If Hamas was willing to justify genocide of Israelis based on the 1948 Palestine war and it’s aftermath, and Israel the permanent occupation of the Palestinians, and I was willing to pay taxes to and thus implicitly support Israel in that conflict, I felt like I had a duty to at the very least get my facts straight about what happened.

So here is a review of that book, and some of my concluding thoughts at the end.

Bias

No book about the Israel Palestinian conflict can be completely free of bias. You always have to pick which events to highlight, which sources to trust. But with that caveat, 1948 is a pretty good pick.

Benny Morris is a liberal Israeli Zionist, albeit one with ever changing, and often maverick, views. However he is not interested in telling a narrative. His aim is to get the facts straight about what happened, and damn the political consequences.

Critics of his book rarely claim he’s lying or deliberately manipulating the reader. Instead they focus on his inability to read Arabic, and his preference for official documents over interviews with participants. Since Israeli, American, and British documents from the period are generally declassified, but Arab ones are not, and the Israelis were far more literate than the Palestinians, this creates a natural blind spot around the Arab/Palestinian narrative.

With that in mind, we can be sure that when Benny Morris says something happened it almost certainly did, but there may be events, perspectives and details he’s simply not privy to. Given the brevity of the book, I don’t think that makes too much difference—see below.

Brevity

I’ve previously read Martin Gilbert’s history of Israel,[1] which dedicates a fair few chapters to the 1948 war. In it he paints a richly detailed picture of the war, and you come out feeling like you’ve got a pretty good understanding of the various different battles and events.

1948 is the opposite. Although spending its 400+ pages entirely focused on this war, it discusses everything very briefly, with a sparsity of detail. Most individual battles get a clause or a sentence, some get a paragraph, and only very occasionally do we get an account from an individual soldier. Massacres and expulsions are similarly given a sentence or two at most—this happened, here are some various different casualty estimates, moving on. What does get a bit more detail and texture is the politics—the mindset of the various decision makers, and how that influenced the progression of the war.

This highlights how Morris is not trying to tell a narrative. He’s not trying to get you to understand what it would feel like to be involved in that war. He’s trying to give you a survey of almost all battles and events in that war, and if he spends 2 pages giving accounts of the battle of Nirim, he won’t be able to tell you anything about the battle of Beit Hanoun. What he does focus on though, is the decision making and background for the events that occurred, since that is critical for putting the war in perspective.

Nonetheless the book is fairly readable, and the brevity mitigates most of our worries about bias—we know we’re discussing pretty much every major event, at least briefly, and since nothing is strongly highlighted, we know that’s not adversely selected for either.

Synopsis

Background

In the 19th century Israel was part of the Ottoman empire. It was sparsely populated, and inhabited by locals not much different from the rest of the Levant. Nationalism wasn’t a thing in those parts, and they viewed themselves as part of a family or a village, not as part of a state.

Towards the end of the 19th century Zionist Jews started immigrating to Israel. They bought land and farmed it, with a dream of eventually creating a Jewish state in the land of their forefathers. Whilst peaceful, that was partly out of a realisation that war would be counterproductive—there definitely were some that knew they would eventually have to take up arms if they wanted to achieve their goal. But they were thinking of war against the Ottomans, and later the British—at this stage, like most European Colonisers, they didn’t think too much about the locals at all.

Over time bad feelings between the locals and the Jews started to brew. Their cultures were very different, and whilst the Jews (usually) bought their land fair and square, the owners of the land were very rarely the ones who lived and worked on it. So those who had worked the land for years were evicted and the Jews took over, inevitably leading to bad blood. At the same time Arab and Palestinian nationalism started to grow, at least in urban areas, although this didn’t have too much impact till at least the 1930s.

In the first world war the British and French took over the Ottoman middle east, and carved it up into a number of protectorates, which over time became independent states—Jordan, Syria, Egypt, Iraq, etc. They didn’t know what to do with Palestine so they ruled it under the British mandate for Palestine.

Over the next thirty years there was lots of nationalist fighting and general nastiness between the Jews and the British, the Palestinian Arabs and the British, and the Jews and the Arabs. This included plain outright terrorism from all sides[2] and generally made the bad blood a lot worse.

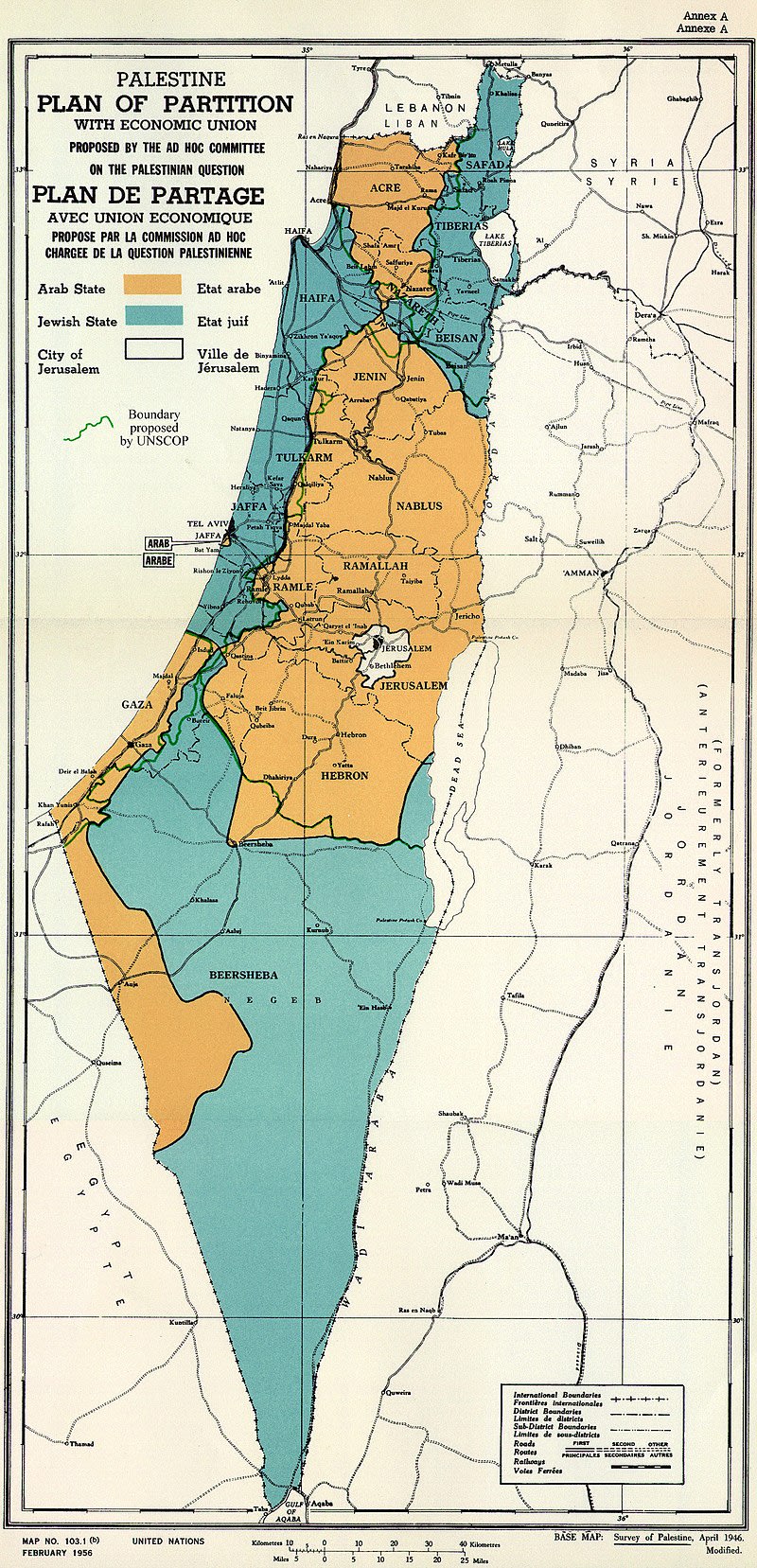

By 1947 the British had had enough and dumped the hot potato onto the UN[3]. The Arabs declared the entire process as an illegitimate attempt to colonise Arab land, and basically refused to have anything to do with it. The Zionists put incredible resources into persuading the Special Committee on Palestine and the member nations that a partition of Palestine was the fairest outcome, and successfully won a two-thirds majority in favour of partition on 29 November 1947. Unsurprisingly given the Arab lack of participation, the partition was much more generous to the Jews than it was to the Palestinians.

The Civil War

The Arabs were incensed at this—from their perspective some immigrants had come to their land, and then suddenly taken half the country for their own state. The neighbouring Arab states declared that if this ever happened they would destroy Israel. The local Arabs organised in loose militias, and started attacking Jewish targets.

At this stage the British had over a hundred thousand troops in the country, but they steadily pulled them out in preparation for the termination of the mandate on the 14th of May 1948. Whilst they quashed any larger battles, and acted as occasional peacemakers, overall they didn’t interfere too much with the civil war.

Whilst the Palestinians were poorly organised, the Yishuv, as the Jewish settlements were known, was effectively a proto-state, which raised taxes, had an army (the Haganah, which grew into the IDF), and efficiently governed itself . Their biggest challenges at this stage were a complete lack of heavy weapons, strict Jewish immigration restrictions, and the need not to provoke the British.

The early part of the civil war involved Palestinian militias attacking Jewish settlements and convoys. Whilst the well organised Haganah easily drove off the ragtag attacks on the settlements, the convoys were much harder to protect, which almost led to the collapse of parts of the Yishuv. The Haganah often carried out reprisal attacks on neighbouring villages which were suspected of being the source or harbouring these militias, but these were little more than raids, rather than attacks aimed at gaining territory. There was also plenty of terrorism by both sides.

The presence of the British made it impossible for the Arab states to invade, or for the Haganah to take over new territory. By April though it was clear that if the Yishuv wasn’t to starve, they would have to ensure contiguous control over all the areas that contained Jewish settlements. They also needed to ensure defensible borders in preparation for an invasion by the neighbouring Arab states. By then most of the British troops had left the country, and so the Haganah kicked off a campaign to conquer villages in or near Jewish areas and along supply routes, and to expel the villagers.

It was during this campaign that the Irgun/Lehi carried out the Deir Yassin massacre. This was exaggerated[4] in the Palestinian press, which backfired and caused large numbers of Palestinians to flee areas adjacent to the Yishuv.

By the time the last British troops left Palestine, the Yishuv controlled a contiguous strip of land that encompassed the vast majority of their settlements. Local Palestinian resistance was crushed, and many had fled en-masse.

Invasion

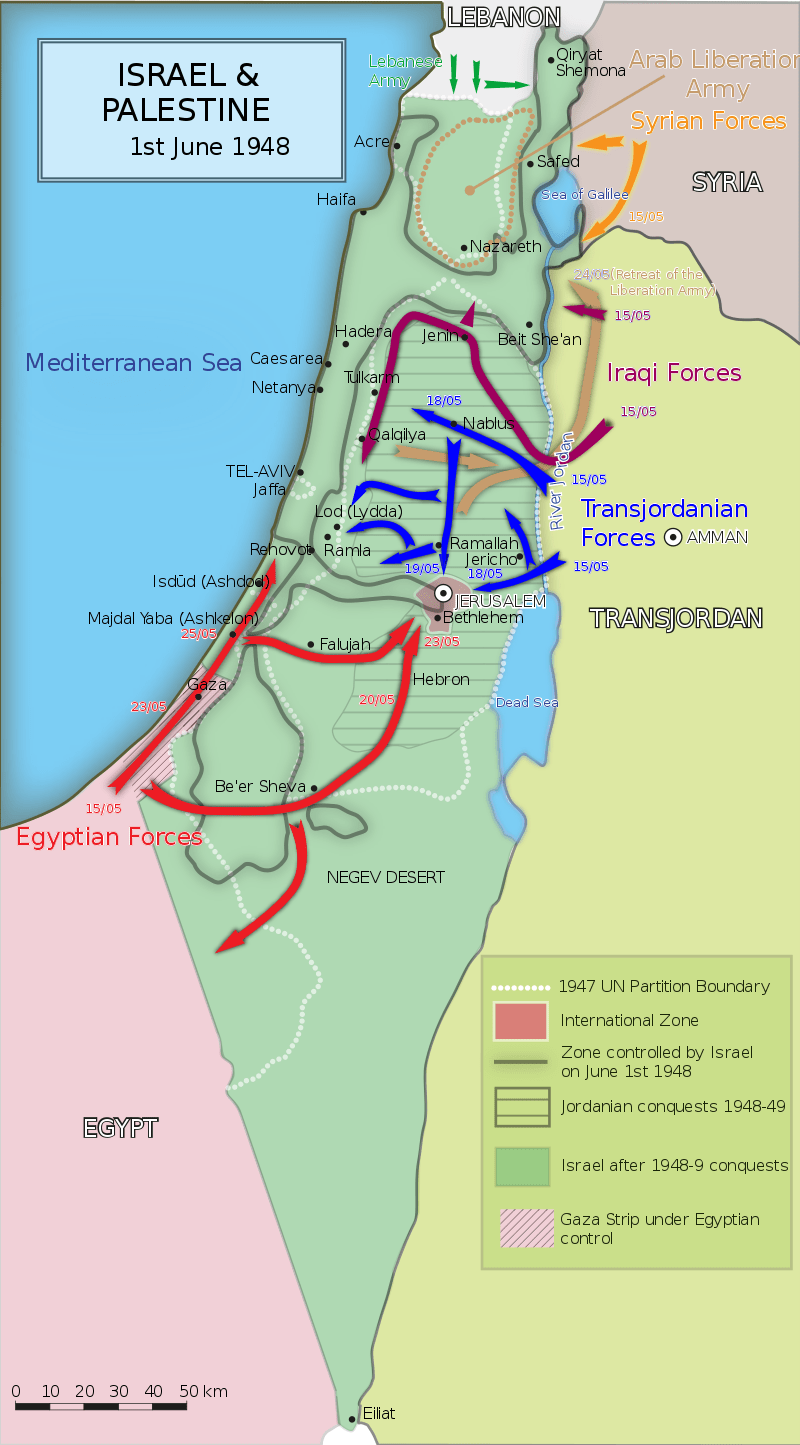

On the 15th of May the State of Israel declared independence. Simultaneously the neighbouring Arab states, all of which had been waiting for the Mandate to be over, invaded.

On paper the invading armies were far stronger than the Haganah, which had only light arms. They had tanks, heavy guns, air forces, and were much larger. However they were poorly organised and trained, far from their supply lines, using badly maintained equipment, and were low on ammunition.

They also all had their own agendas. The Jordanians had secretly negotiated with the Yishuv for peace, hoping to take the west bank for themselves, and leave the rest for Israel. The Egyptians also wanted a slice of Palestine for themselves and wanted to counter Jordanian ambitions. The Iraqis might have been aiming to control the Haifa oil refinery. The Lebanese failed to attack at all, knowing they were too weak to risk a war. The Syrians were also weak, and were never too serious a threat.

They quickly overran Palestinian areas and made some small advances into Israeli controlled territory, but were quickly stopped with heavy losses. From then on they were on the defensive, never making any serious offensives.

The Jordanians did however threaten the road to Jerusalem, risking starvation for the 100,000 odd Jewish inhabitants, and the Egyptians cut off a huge area of Jewish settlement in the northern Negev desert. The IDF tried desperately to reverse these losses, but apart from minor gains this was mostly unsuccessful. A UN imposed, one month long truce kicked in on 11th June.

An arms embargo had been imposed on all sides by the UN, but whilst the Arab army were dependent on the British for resupply, the Yishuv had extensive experience smuggling arms into the country. Boosted by an influx of both Jewish immigrants and weapons, over the course of the truce (and the rest of the war) the IDF grew steadily stronger whilst the Arab armies failed to make use of the break.

The 10 days

After the truce was up the IDF immediately went on the offensive on all fronts, taking large swathes of the western Galilee, biting into the small Syrian advance north of the Sea of Galilee, and pushing back the Jordanians near Lod and Ramle. Whenever the IDF conquered an Arab village they expelled all inhabitants and burned down the houses so the locals couldn’t return. This was driven partly by military necessity—they didn’t have the manpower to guard against attacks from within, but also partly from vengeance and a desire to achieve a mostly Jewish state.

Despite making significant advances, they failed to achieve their main military aims—securing the road to Jerusalem, and linking up with the besieged northern Negev enclave. By the end of the 10 days the UN imposed another truce, this time of indefinite length.

During this truce the UN considered what to do with Palestine. The original partition was clearly dead with the Egyptians occupying most of the Negev and Israel much of the Galilee, and there were talks of giving the entire Negev to Egypt/Jordan, and the entire Galilee to Israel.

Whilst the truce enabled Israel to rearm and train more troops, it also took a heavy toll—it was forced to maintain a complete war footing and total mobilisation in a small poor country that desperately needed to start developing it’s economy. Both the Egyptians and Jordanians were just a few kms from Tel Aviv, and so the IDF had to be constantly on the alert for any potential attack. The Arab states, fielding small[5] professional armies far from home, had no such issues, and could maintain this situation indefinitely.

Also the Egyptians prevented convoys from entering the Negev pocket (against the terms of the truce), forcing Israel to keep it supplied through it’s minuscule air force.

The final phase

Israel prepared for an operation in the Negev, then pushed a convoy into the pocket. When they Egyptians inevitably attacked, they had their casus belli and attacked. By the time a truce was eventually forced on them by the UN they had linked up with the pocket, encircled 4000 Egyptians in the Feluja pocket, pushed the Egyptians back all the way to Gaza, and taken Beer-Sheba.

A similar operation was planned in the Galilee. When the ALA[6] occupied an Israeli position and sniped from it at Israeli targets, it began, and succeeded in completely occupying the Galilee and even parts of southern Lebanon.

However once again a truce was imposed, and once again Israel was forced to maintain an unsustainable complete mobilisation. Ultimately Ben Gurion decided that the only way to force an armistice was to completely defeat the Egyptians. This time without waiting for any contraventions of the truce, the IDF attacked into the Sinai, routing the Egyptians and almost encircling Gaza, before the IDF pulled back to the border of Mandatory Palestine under British pressure. They then aimed for a smaller encirclement of Gaza at Rafah, until the Egyptians agreed to enter into Armistice negotiations.

Armistice

The Egyptians were now keenly aware that they were sorely outmatched by Israel. They eventually agreed to an armistice whereby they pulled back to the Sinai (except for Gaza, which they controlled till 1967), and large parts of the Egyptian/Mandatory Palestine border were declared demilitarised zones.

This gave the other Arab countries an excuse to pursue their own peace. The Lebanese quickly agreed in return for an Israeli withdrawal back to the border. The Jordanians originally haggled for all or part of the Negev, but the IDF (peacefully) occupied the entirety of the Negev up to Eilat in March, presenting the Jordanians with a fait accompli. Ultimately the Jordanians kept the West Bank, which they controlled till 1967, and the Israelis everything else. The Syrians pulled out of the small parts of Palestine they had conquered, which were declared demilitarised zones.

Conclusion

In his final chapter Morris finally loses the persona of the dispassionate historian, and starts giving his own opinions and interpretations of the War. I think this chapter definitely does reflect his bias, so I’m not going to go over it here, but it will inform some of the opinions I give in the next few sections.

War Crimes

Expulsion

Most Palestinians and Arab leaders had an explicit agenda to expel all Jews from Israel, whilst others were prepared to potentially grant the Jews a small semi-autonomous zone and severely curtail immigration. However they were never very successful in the war, conquering only a handful of Jewish villages[7].

The IDF pretty consistently expelled all Arabs from villages they conquered, although there are a fair number of exceptions. Whilst never spelled out as such in official policy at the highest levels, it’s clear that this was more or less desired by the top brass. At first this was driven by military necessity—during the civil war the villages were used as bases by irregulars to attack Jewish convoys, and it didn’t have the manpower to police these villages. This remained more or less necessary for the rest of the war, but it’s clear that at some point the IDF was also deliberately aiming to achieve a favourable Jewish/Arab ratio in the new state, and prevent any future 5th column.

Some 400 Arab villages were evacuated and 700,000 to 900,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled from Israel over the course of the war. Despite numerous UN resolutions to the contrary they have never been allowed to return[8].

Massacres

Differentiating between collateral damage and deliberate targeting of civilians is always hard in urban fighting, and is always a point of contention (and often a question of definition).

The Palestinian militias and the Lehi/Irgun both happily targeted civilians in the civil war, whilst the Haganah was somewhat more restrained, as were the Arab armies. In the few cases where Arab armies conquered Jewish villages, they usually prevented Palestinian irregulars from executing the POWs. Palestinians probably massacred some 200 Jewish civilians/POWs in cold blood, and Morris estimated that Jewish forces massacred some 800 or so. Again this difference is largely due to Israel being more successful in the war. There were also a handful of reported cases of rape, but we expect there are far more we don’t know about.

Morris argues that this is roughly in line with what happens in almost all wars involving Urban areas, and even that the number is on the lower end of what we would expect. Based on my knowledge of military history this seems roughly correct.

Neither side took prisoners in the Civil war, but Morris considers that legitimate—the British wouldn’t have allowed them to create prison camps so they had little choice. Post mandate both sides took prisoners and (despite numerous exceptions) generally treated them well.

Conquest

It was the explicit aim of the Palestinians and Arab Armies to conquer the entirety of mandatory Palestine, albeit one they were unsuccessful in. Unofficially Jordan was hoping to occupy the west bank, and Egypt to occupy Gaza, the Negev desert, and the southern West Bank. Jordan and Egypt ended up occupying the west bank/Gaza respectively until 1967.

Israel’s initial aims in the civil war were to conquer contiguous areas of territory needed to link up Jewish settlements, and allow convoys to flow. That later morphed into conquering all areas assigned to them under the partition plan, and eventually into conquering as much of mandatory Palestine as they could get their hands on.

Scattered Thoughts

If all you wanted was a historical account of what occurred, and a discussion of the book, you can stop here. Here I’m going to very briefly list some of the less controversial conclusions I drew reading the book.

Both the Israeli and Palestinian narratives of the 1948 war have some merit, but are also often incorrect. I think however that discussing them in this forum wouldn’t be helpful, and would lead to accusations that I’m misrepresenting their narrative.

Even ignoring everything that happened afterwards, it’s understandable why Palestinians would hate Israelis. They were expelled from their land by foreigners, and many were killed.

Even ignoring everything that happened afterwards, it’s understandable why Israelis would hate Palestinians. There were many anti Jewish riots pre-1947, Israel was prepared to accept a peaceful partition of the land, and instead were forced into a war for their survival in which many of them were killed.

I think the Yishuv can be rightly criticised for attempting to create a Jewish state in Palestine, and not sufficiently thinking through the consequences of this effort to the locals who already lived there. Even if the Palestinians started the war, and Israel’s hand was forced from then on, the partition plan represented a major injustice to the Palestinians, and Israel should recognise that.

I think the party who really doesn’t get sufficiently blamed here is the British. They threw their burden onto the UN, but were unprepared to actually carry out the partition plan the UN decided on. This was despite having over 100,000 troops in the country, and being the arms supplier for the Arab countries. If they’d decided to enforce partition it would have been a fait accompli. Instead, once they decided to abandon Palestine the partition plan was doomed. British officers even commanded the Jordanian Arab Legion in the war!

This is still nowhere near sufficient to understand the current state of the Israel/Palestine conflict. If I were to guess what the present would look like based only on events up to 1949. I would assume Palestinian refugees either returned to Israel or the West Bank, or eventually settled where they fled. Jordan and Egypt either annexed the West Bank/Gaza, or established an independent state/s there. In order to really understand why things look like they do, we need to understand the 1967 war and its causes—hopefully my next project. Edit: I have now read and reviewed Benny Morris’s Righteous Victims, which helps answer this question.

- ^

Incidentally, Accused by Benny Morris of being inaccurate with a notable pro Israel bias.

- ^

- ^

The British wanted to give the entire mandate to Arabs to preserve their good relations with the neighbouring Arab states, but couldn’t due to American pressure which sympathised with the Zionist cause (and relied on the Jewish vote). They hoped the UN would do so as it included a lot of Arab states, and a lot more states that relied on Arab oil.

- ^

That’s not to say the realities of the massacre weren’t terrible—they were.

- ^

Relative to their larger populations.

- ^

Arab Liberation Army, an army of volunteers that had fought the Yishuv during the civil war, and still operated in the Galilee.

- ^

All Jews in conquered Jewish villages were killed, expelled, or imprisoned.

- ^

Israel has pointed out a similar number of Jews were expelled from Arab countries, lost all their property and their citizenship, and haven’t been allowed to return. Whilst true, Israel wouldn’t have allowed those Palestinians who fled to return to their villages either way, so it’s kind of a moot point. At the same time, allowing in all Palestinian refugees to Israel would end Israel as a Jewish state, so it’s clear this is something that Israel just will not do.

There are sources saying that Israeli leaders were publicly willing to accept partition, but privately not. I’m uncertain how true this is, but haven’t been able to find any push back on it. (I brought it up in a FB discussion and the pro-Israeli participants just ignored it.)

https://www.salon.com/2015/11/30/u_n_voted_to_partition_palestine_68_years_ago_in_an_unfair_plan_made_even_worse_by_israels_ethnic_cleansing/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1937_Ben-Gurion_letter

My impression reading the book is that whilst the Israelis definitely had ambitions on far more, they were prepared to grudgingly accept the partition plan. They were heavily dependent on international support for their cause and far weaker than the surrounding Arab States so would have had no incentive for war in the founding days of the state if it wasn’t forced on them.

Certainly there weren’t any concrete plans by the Yishuv or Haganah to take over any land pre the UN partition vote. This is despite the Haganah generally being quite well organised in that way, and having lots of contingency plans prepared. On the other hand that may well have been as a result of uncertainty about what the UN partition plan would mean in concrete terms, especially for the British.

Whether things would have stayed peaceful long term if the Palestinians had accepted partition, or war would have eventually flared up, is anybody’s guess. In practice what happened was that the Arabs denounced the partition plan and initiated concrete efforts to undermine it, and Israel accepted it and mostly kept to it till far later in the war.

Thank you, I appreciated this post quite a bit. There’s a paucity of historical information about this conflict which isn’t colored by partisan framing, and you seem to be coming from a place of skeptical, honest inquiry. I’d look forward to reading what you have to say about 1967.

I have heard this before but never understood what it meant. Did the people who worked the land respect the ownership of the previous owners, for example by paying rest or by being employed by the previous owners, but they just did not respect the sale? Or did the people who worked the land consider themselves to be owners or didn’t have the same concept of ownership as we do today?

Just read in Morris’s Righteous Victims:

It seems you’ve stepped on quite a land mine here, and the following is mostly just vague guesses.

As far as I can make out it dates back to the Ottoman land code of 1858 where for various reasons a lot of land was declared owned by the government, which would collect a tax in lieu of rent.

So in one case the Ottoman empire sold a large tract of land to a Lebanese Effendi, who then sold it to the Yishuv. There was an village on this land which had been settled for some 60+ years, and despite protests to the Ottoman government the villagers were all evicted by the Jewish settlers.

It seems the villagers paid a tithe. I suppose at first they would have paid the tithe to the Ottoman government, which would have seemed normal to them (and more like a tax), then they switched to paying a Lebanese Effendi, which wouldn’t have made any difference to them either way. And then suddenly they were sold again, and evicted off their land, which would have felt very wrong given they’d been living there all their life, and viewed it as their land.

Forgive me, I have strongly downvoted this dispassionate, interesting, well-written review of what sounds like a good book on an important subject because I want to keep politics out of Less Wrong.

This is the most hot-button of topics, and politics is the mind-killer. We have more important things to think about and I do not want to see any of our political capital used in this cause on either side.

typo-wise you have a few uses of it’s (it is) where it should be its (possessive), and “When they Egyptians” should probably read “When the Egyptians”.

I did enjoy your review. Thank you for writing it. Would you delete it and put it elsewhere?

I disagree-voted because while politics is the mind-killer, I think LW’s implicit norm, and that of many LW users, against discussion of politics on the site goes too far. And this article was both informative, and an instance of someone seeking out info to update their models during a time especially adverserial to clear-eyed thinking on the Israel-Palestine conflict. That’s attempting to become less-wrong on hard mode, which I want more of. And since this post does it better than the average post on politics here, I strong up-voted it.

EDIT: I, ah, forgot to strong up-vote. I feel a bit sheepish about that rant, now. Though I have gone and strong up-voted the article.

Yeah, this article is more rational than 95% of politics-related content on LW.