Ethodynamics of Omelas

Epistemic status: just kidding… haha… unless...

Introduction

A great amount of effort has been expended throughout history to decide the matter of “what is good” or “what is right” [citation needed]. This valiant but, let’s face it, not tremendously successful effort has produced a number of possible answers to these questions, none of which is right, if history is any indication. Far from this being their only problem, the vast majority of these answers also suffer from the even more serious flaw of not being able to produce anything resembling a simple quantitative prediction or computable expression for the thing they are supposed to discuss, and instead prefer to faff about with qualitative and ambiguously defined statements. Not only they aren’t right; they aren’t even wrong.

More recently, and in certain premises more than others, a relatively new-ish theory of ethics has gained significant traction as the one most suited to a properly scientific, organized and rational mind—the theory of Utilitarianism. This approach to ethics postulates that all we have to do to solve it is to define some kind of “utility function” (TBD) representing all of the “utility” of each individual who is deemed a moral subject (TBD) via some aggregation method (TBD) and in some kind of objective, commensurable unit (TBD). It is then a simple matter of finding the policy which maximizes this utility function, and there you go—the mathematically determined guide to living the good life, examined down to however many arbitrary digits of precision one might desire! By tackling the titanic task head on, refusing to bow to the tyranny of vague metaphysics, and instead looking for the unyielding and unforgiving certainty of numbers, Utilitarianism manages one important thing:

Utilitarianism manages to be wrong.

Now, I hope the last statement doesn’t ruffle too many feathers. If it helps reassure any of those who may have felt offended by it, I’ll admit that this study also deals unashamedly into Utilitarianism; and thus, by definition, it is also wrong. But one hopes, at least, wrong in an interesting enough way, which is often the best we can do in such complex matters. The object of this work is the aggregation method of utility. There are many possible proposals, none, in my opinion, too satisfactory, all vulnerable to falling into one or another horrible trap laid by the clever critic which our moral instincts refuse to acknowledge as possibly ever correct.

A common one, which we might call Baby’s First Utility Function, is total sum utilitarianism. In this aggregation approach, more good is good. Simple enough! Ten puppies full of joy and wonder are obviously better than five puppies full of joy and wonder, even an idiot understands as much. What else is left to consider? Ha-ha, says the critic: but what if a mad scientist created some kind of amazing super-puppy able to feel joy and wonder through feasting upon the mangled bodies of all others? What if the super-puppy produced so much joy that it offsets the suffering it inflicts? Total sum utilitarianism tells us that if the parameters are right, we ought to indeed accept the numbers and with them the super-puppy and the pain to be found within its joyous and drooling jaws, which isn’t the common sense ethical approach to the problem (namely, take away the mad scientist’s grant funding and have them work on something useful, like a RCT on whether fresh mints cause cancer). But even without super-puppies, total sum utilitarianism lays more traps for us. The obvious one is that if more total utility is always good, then as long as life is above the threshold for positive utility (TBD), it’s a moral imperative to simply spawn more humans[1]. This is known as the “repugnant conclusion”, named so after the philosopher who reached it took a look at the costs of housing and childcare in his city. Obviously, as our lifestyle has improved and diversified, our western sensibilities have converged towards the understanding that children are like wine: they get better as they age, and are only good in moderation. We’d like our chosen ethical system not to reprimand us too harshly for things we’re dead set on doing anyway, thank you very much.

Now, seeking to fix these issues, the philosopher who through a monumental cross-disciplinary effort has learned not only addition, but division too, may thus come up with another genius idea: average utilitarianism. Just take that big utility boi and divide it by the number of people! Now the number goes up only if each individual person’s well-being does as well; simply creating more people changes nothing, or makes the situation worse if you can’t keep up with the standards of living. This seems more intuitive; after all, no one ever personally experiences all of the utility anyway. There is no grand human gestalt consciousness that we know of (and I’m fairly confident, not more than one or two that we don’t). So average utility is as good as it gets, because as every statistician will tell you, averages are all politicians need to know about distributions before taking monumental decisions. Fun fact, they usually cry while telling you this.

Now, while I’m no statistician, I am sympathetic to their plight, and can see full well how averages alone can be deceptive. After all, a civilization in which everyone has a utility of 50 and one in which half of everyone has a utility of 100 and the other half has a utility of “eat shit” are quite different, yet they have the same average utility. And the topic of unfairness and inequality in society has been known to rouse some strong passions in the masses [citation needed]. There are good reasons to find ways to weigh this effect into your utility function, either because you’re one of those who eat shit, or because you’re one of those who have a utility of 100 but have begun noticing that the other half of the population is taking a keen interest in pointy farming implements.

To overcome these problems, in this study, I draw inspiration from that most classic of teachers, Nature, and specifically from its most confusing and cruel lesson, thermodynamics. I suggest the concepts of ethodynamics as an equivalent of thermodynamics applied to utilitarian ethics, and a quantity called the free utility as the utility function to maximize. I then apply the new method to the rigorous study of a known toy problem, the Omelas model [LeGuin, 1973] to showcase its results.

Free utility

We define the free specific utility for a closed society as:

where is the average expected utility, is the entropy of the distribution of possible utility outcomes, and is a free “temperature” parameter which expresses the importance we’re willing to give to equality over total well-being. If you believe that slavery is fine as long as the slaves are making some really nice stuff, your “ethical temperature” is probably very close to zero; if you believe that the Ministry of Equalization should personally see to it that the legs of those who are born too tall are sawed off so that no one feels looked down on, then your temperature is approaching infinity. Most readers, I expect, will place somewhere in between these two extremes.

The other quantities can be defined with respect to a probability distribution of outcomes, :

With this definition, the free energy will go up with each improvement in average utility and down with each increase in inequality, at a rate that depends on the temperature parameter. We can then identify two laws of ethodynamics:

any conscientious moral actor ought to try to maximize according to their chosen temperature;

absent outside intervention, in a closed society, Moloch [Alexander, 2014] tends to drive down.

The first law is really more of a guideline, or a plea. The second law is, as far as I can tell, as inescapable as its thermodynamical cousin, and possibly literally just the same law with fake glasses and a mustache.

Those who should actually maybe walk back to Omelas

For a simplified practical example of this model we turn to the well known Omelas model, which provides the simplest possible example of a society with high utility but also non-zero entropy. The model postulates the following situation: a city called Omelas exists, with an unspecified amount of inhabitants. Of these, live in what can only be described as joyous bliss, in a city as perfect as the human mind can imagine. The last one, however, is a child who lives in perpetual torture, which is through unspecified means absolutely necessary to guarantee everyone else’s enjoyment. The model is somewhat imprecise on the details of this arrangement (why a child? What happens when they come of age? Do they just turn into another happy citizen and are replaced by a newborn? Do they die? Do they simply live forever, frozen in time by whatever supernatural skulduggery powers the whole thing?) or the demographics of Omelas, so we decide to simplify it further by removing the detail that the sufferer has to be a child. Instead, we describe our model with the following utility distribution:

where the zero of utility is assumed to be the default state of anyone who lives outside of Omelas, and units of utility are arbitrary.

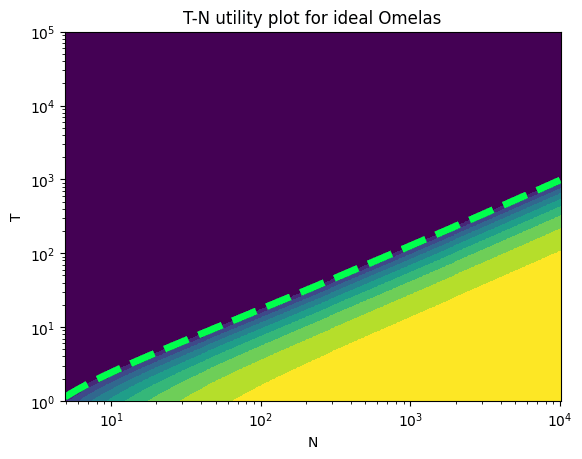

In this ideal model of Omelas, the specific free utility can be found as

as a function of temperature and population. For large enough , we can apply Stirling’s approximation to simplify:

leading to

This has the consequence that the free utility converges to 1 as the population of Omelas grows, independently of temperature. The boundary across which the crossover from negative to positive utility happens is approximately:

For any populations larger than the one marked by this line, the existence of Omelas is a net good for the world, and thus its population ought to increase. Far from walking away, moral actors ought to walk towards it! This is not even too surprising a result on consideration: given that one poor child is being tortured regardless, we may as well get as much good as possible out of it.

But this unlimited growth should raise suspicion that this model might be a tad bit too perfect to be real, much like spherical cows, trolley problems, and Derek Zoolander. There’s no such thing as a free lunch, even if the child is particularly plump. What, are we to believe that whatever magical bullshit/deal with Cthulhu powers Omelas’ unnatural prosperity has no limit whatsoever, that a single tortured person can provide enough mana to cast Wish on an indefinite amount of inhabitants? Should we amass trillions and trillions on the surface of a Dyson sphere centered on Omelas? Child-torture powered utopias, we can believe; but infinitely growing child-torture powered utopias are a bridge too far!

In our search for a more realistic version of an enchanted enclave drawing energy from infant suffering we ought thus to put a limit to the ability of Omelas to infinitely scale its prosperity up with its number of citizens. Absent any knowledge about the details of the spells, conjurings and pacts that power the city to build a model of, we have to do like good economists and do the next best thing: pull one out of our ass. We therefore postulate that the real Omelas model provides a total utility (to be equally divided between its non-tortured inhabitants) of:

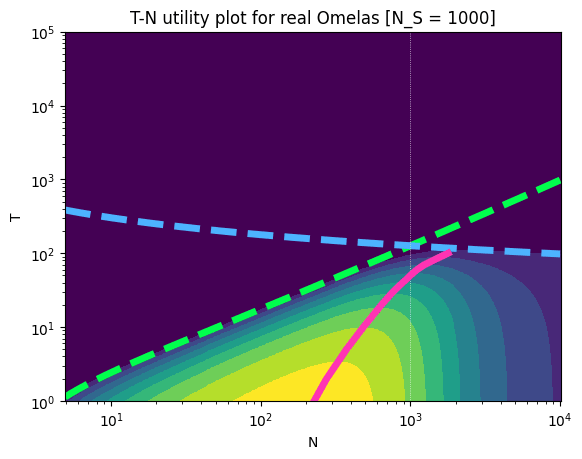

This logistic function has all the desired properties. It is approximately linear in with slope 1 around 0, then slowly caps as soon as the population grows past a certain maximum support number . We can then replace it in the free utility:

In the limit of low , the zero line described above still applies. Meanwhile, for high , we see a new zero line:

This produces a much more interesting diagram:

We see now that optimization is no longer trivial. To begin with, there is a temperature above which the existence of Omelas will always be considered intolerable and a net negative. This is roughly the temperature at which the two zero lines cross, so:

For , this corresponds to . In addition, even below this temperature, the free utility has a maximum in for each value of . In other words, there is an optimum of population for Omelas. People with will find themselves able to tolerate Omelas, on the whole, but will also converge towards a certain value of its population. If they are actual moral actors and not just trying to signal their virtue, they are thus expected to walk away from or towards Omelas depending on its current population. Too little people and the child’s sacrifice is going to waste; too many, and the spreading out of too few resources make things miserable again.

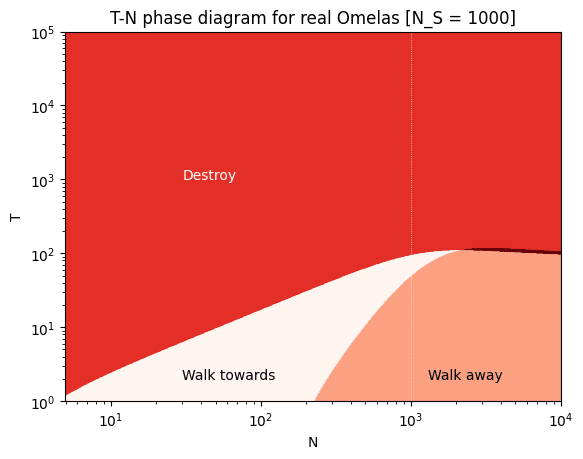

The phase diagram can be built by coloring regions based on the sign of both the free energy and its derivative in , :

the almost white region is the one in which both and are positive; here Omelas is a net good, but it can be made even better if more people flock to it; this is the walk towards phase;

the orange region is the one in which is positive but is negative; here Omelas is a net good, but it can be made even better if someone conscientious enough makes willingly the sacrifice of leaving it, so that others may enjoy more its scarce and painfully earned resources; this is the walk away phase which the original work hints at;

the bright red region is the one in which is negative even though is positive; here Omelas is seen as a blight upon the world, a haven of unfairness which offends the eyes and souls of those who seek good. No apologies nor justifications can be offered for its dark sacrificial practices; the happiness of the many doesn’t justify the suffering of the very few. For those who find themselves in this region, walking away isn’t enough, and is mere cowardice. Omelas must be razed, its palaces pillaged, its walls ground to dust, its populace scattered, its laws burned, and the manacles that shackle the accursed child shattered by the hammer of Justice, that they may walk free and happy again. This is the destroy phase;

the thin dark red sliver is the region in which both and are negative. We don’t talk about that one.

Conclusions

This study has offered what I hope was an exhaustive treatment of the much discussed Omelas model, put in a new utilitarian framework that tries to surpass the limits of more traditional and well-known ones. I have striven to make this paper a pleasant read by enriching it with all manners of enjoyable things: wit, calculus, and a non indifferent amount of imaginary child abuse[2]. But I’ve also tried to endow it with some serious considerations about ethics, and to contribute something new to the grand stream of consciousness of humanity’s thought on the matter that has gone on since ancient times. Have I succeeded? Probably no. Have I at least inspired in someone else such novel and deep considerations, if only by enraging them so much that the righteous creative furor of trying to rebut to my nonsense gives them the best ideas of their lives? Also probably no.

But have I at least written something that will elicit a few laughs, receive a handful of upvotes, and marginally raise my karma on this website by a few integers, thus giving me a fleeting sense of accomplishment for the briefest of moments in a world otherwise lacking any kind of sense, rhyme, reason, or purpose?

That, dear readers, is up to you to decide.

- ^

Actually a less discussed consequence is that if it instead turned out that life is generally below that threshold (TBD), the obvious path forward is that we all ought to commit suicide as soon as possible. This is also frowned upon.

- ^

Your mileage may vary about how enjoyable these things actually are. Not everyone likes calculus.

- Voting Results for the 2023 Review by (6 Feb 2025 8:00 UTC; 86 points)

- Is there something fundamentally wrong with the Universe? by (12 Sep 2023 12:02 UTC; 6 points)

- 's comment on Are we confident that superintelligent artificial intelligence disempowering humans would be bad? by (EA Forum; 25 Nov 2023 21:36 UTC; 3 points)

- 's comment on Infinite Ethics: Infinite Problems by (17 Aug 2023 7:50 UTC; 2 points)

This delightful piece applies thermodynamic principles to ethics in a way I haven’t seen before. By framing the classic “Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” through free energy minimization, the author gives us a fresh mathematical lens for examining value trade-offs and population ethics.

What makes this post special isn’t just its technical contribution—though modeling ethical temperature as a parameter for equality vs total wellbeing is quite clever. The phase diagram showing different “walk away” regions bridges the gap between mathematical precision and moral intuition in an elegant way.

While I don’t think we’ll be using ethodynamics to make real-world policy decisions anytime soon, this kind of playful-yet-rigorous exploration helps build better abstractions for thinking about ethics. It’s the kind of creative modeling that could inspire novel approaches to value learning and population ethics.

Also, it’s just a super fun read. A great quote from the conclusion is “I have striven to make this paper a pleasant read by enriching it with all manners of enjoyable things: wit, calculus, and a non indifferent amount of imaginary child abuse”.

That is the type of writing I want to see more of! Very nice.