If AI alignment is only as hard as building the steam engine, then we likely still die

Cross-posted from my website.

You may have seen this graph from Chris Olah illustrating a range of views on the difficulty of aligning superintelligent AI:

Evan Hubinger, an alignment team lead at Anthropic, says:

If the only thing that we have to do to solve alignment is train away easily detectable behavioral issues...then we are very much in the trivial/steam engine world. We could still fail, even in that world—and it’d be particularly embarrassing to fail that way; we should definitely make sure we don’t—but I think we’re very much up to that challenge and I don’t expect us to fail there.

I disagree; if governments and AI developers don’t start taking extinction risk more seriously, then we are not up to the challenge.

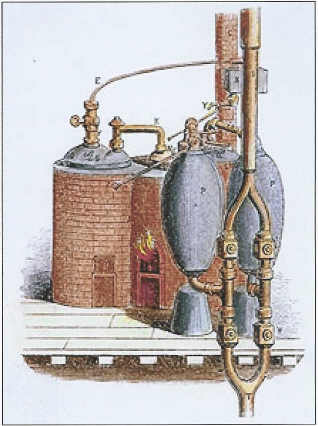

Thomas Savery patented the first commercial steam pump in 1698.[1] The device used fire to heat up a boiler full of steam, which would then be cooled to create a partial vacuum and draw water out of a well. Savery’s pump had various problems, and eventually Savery gave up on trying to improve it. Future inventors improved upon the design to make it practical.

It was not until 1769 that Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot developed the first steam-powered vehicle, something that we would recognize as a steam engine in the modern sense.[2] The engine took Cugnot four years to develop. Unfortunately, Cugnot neglected to include brakes—a problem that had not arisen in any previous steam-powered devices—and at one point he allegedly crashed his vehicle into a wall.[3]

Imagine it’s 1765, and you’re tasked with building a steam-powered vehicle. You can build off the work of your predecessors who built steam-powered water pumps and other simpler contraptions; but if you build your engine incorrectly, you die. (Why do you die? I don’t know, but for the sake of the analogy let’s just say that you do.) You’ve never heard of brakes or steering or anything else that automotives come with nowadays. Do you think you can get it all right on the first try?

With a steam engine screwup, the machine breaks. Worst case scenario, the driver dies. ASI has higher stakes. If AI developers make a misstep at the end—for example, the metaphorical equivalent of forgetting to include brakes—everyone dies.

Here’s one way the future might go if aligning AI is only as hard as building the steam engine:

The leading AI developer builds an AI that’s not quite powerful enough to kill everyone, but it’s getting close. They successfully align it: they figure out how to detect alignment faking, they identify how it’s misaligned, and they find ways to fix it. Having satisfied themselves that the current AI is aligned, they scale up to superintelligence.

The alignment techniques that worked on the last model fail on the new one, for reasons that would be fixable if they tinkered with the new model a bit. But the developers don’t get a chance to tinker with it. Instead what happens is that the ASI is smart enough to sneak through the evaluations that caught the previous model’s misalignment. The developer deploys the model—let’s assume they’re being cautious and they initially only deploy the model in a sandbox environment. The environment has strong security, but the ASI—being smarter than all human cybersecurity experts—finds a vulnerability and breaks out; or perhaps it uses superhuman persuasion to convince humans to let it out; or perhaps it continues to fake alignment for long enough that humans sign it off as “aligned” and fully roll it out.

Having made it out of the sandbox, the ASI proceeds to kill everyone.

I don’t have a strong opinion on how exactly this would play out. But if an AI is much smarter than you, and if your alignment techniques don’t fully generalize (and you can’t know that they will), then you might not get a chance to fix “alignment bugs” before you lose control of the AI.

Here’s another way we could die even if alignment is relatively easy:

The leading AI developer knows how to build and align superintelligence, but alignment takes time. Out of fear that a competitor beats them, or out of the CEO being a sociopath who wants more power[4], they rush to superintelligence before doing the relatively easy work of solving alignment; then the ASI kills everyone.

The latter scenario would be mitigated by a sufficiently safety-conscious AI developer building the first ASI, but none of the frontier AI companies have credibly demonstrated that they would do the right thing when the time came.

(Of course, that still requires alignment to be easy. If alignment is hard, then we die even if a safety-conscious developer gets to ASI first.)

What if you use the aligned human-level AI to figure out how to align the ASI?

Every AI company’s alignment plan hinges on using AI to solve alignment, a.k.a. alignment bootstrapping. Much of my concern with this approach comes from the fact that we don’t know how hard it is to solve alignment. If we stipulate that alignment is easy, then I’m less concerned. But my level of concern doesn’t go to zero, either.

Recently, I criticized alignment bootstrapping on the basis that:

it’s a plan to solve a problem of unknown difficulty...

...using methods that have never been tried before...

...and if it fails, we all die.

If we stipulate that the alignment problem is easy, then that eliminates concern #1. But that still leaves #2 and #3. We don’t know how well it will work to use AI to solve AI alignment—we don’t know what properties the “alignment assistant” AI will have. We don’t even know how to tell whether what we’re doing is working; and the more work we offload to AI, the harder it is to tell.

What if alignment techniques on weaker AIs generalize to superintelligence?

Then I suppose, by stipulation, we won’t die. But this scenario is not likely.

The basic reason not to expect generalization is that you can’t predict what properties ASI will have. If it can out-think you, then almost by definition, you can’t understand how it will think.

But maybe we get lucky, and we can develop alignment techniques in advance and apply them to an ASI and the techniques will work. Given the current level of seriousness with which AI developers take the alignment problem, we’d better pray that alignment techniques generalize to superintelligence.

If alignment is easy and alignment generalizes, we’re probably okay.[5] If alignment is easy but doesn’t generalize, there’s a big risk that we die. More likely than either of those two scenarios is that alignment is hard. However, even if alignment is easy, there are still obvious ways we could fumble the ball and die, and I’m scared that that’s what’s going to happen.

- ↩︎

History of the steam engine. Wikipedia. Accessed 2025-12-22.

- ↩︎

Nicolas-Joseph Cugnot. Wikipedia. Accessed 2025-12-22.

- ↩︎

Dellis, N. 1769 Cugnot Steam Tractor. Accessed 2025-12-22.

- ↩︎

This is an accurate description of at least two of the five CEOs of leading AI companies, and possibly all five.

- ↩︎

My off-the-cuff estimate is a 10% chance of misalignment-driven extinction in that scenario—still ludicrously high, but much lower than my unconditional probability.

This is pointing at a way in which solving alignment is difficult. I think a charitable interpretation of Chris Olah’s graph takes this kind of difficulty into account. Therefore I think the title is misleading.

I think your discussion of the AI-for-alignment-research plan (here and in your blog post) points at important difficulties (that most proponents of that plan are aware of), but also misses very important hopes (and ways in which these hopes may fail). Joe Carlsmith’s discussion of the topic is a good starting point for people who wish to learn more about these hopes and difficulties. Pointing at ways in which the situation is risky isn’t enough to argue that the probability of AI takeover is e.g. greater than 50%. Most people working on alignment would agree that the risk of that plan is unacceptably high (including myself), but this is a very different bar from “>50% chance of failure” (which I think is an interpretation of “likely” that would be closer to justifying the “this plan is bad” vibe of this post and the linked post).

What if your first model isn’t perfectly aligned, but at least wants to be? It understands the problem, as well as we do, it wants to solve it, and it isn’t trying to trick us into thinking its aligned, it’s trying to become more aligned? It regards its misalignment, once it identifies its nature, as bad habits it wants to break?

I assume you mean that it wanted human flourishing or something similar, so it’s figuring out exactly what that is and how to work toward it.

Choosing an alignment target wisely might make technical alignment a bit easier, but probably not a lot easier. So I think this is a fairly separate topic from the rest of the post. But it’s a topic I’m interested in, so here’s a few cents worth:

Or do you mean Corrigibility as Singular Target? If the main goal is to be correctable (or roughly, to follow instructions), then I think the scheme works in principle- but you’ve still got to get it aimed at that target pretty precisely, because it’s going to pursue whatever you put in there—probably with fairly clumsy training methods.

If you aimed it at a concept/value like human flourishing, that’s great IF you defined the target exactly right; if not, and you haven’t solved the fundamental problem with adding corrigibility as a secondary feature, it’s not going to help if you aimed it at the wrong target. It will self-correct toward the wrong target you trained in. I wouldn’t say it in this polarizing way, but I agree with Jeremy Gillen that The corrigibility basin of attraction is a misleading gloss in this important way.

If you got it to value human flourishing, that’s great, and it will be in a basin of alignment in a weak sense: it will try to correct mistakes and uncertainties by its criteria. If I love human fluorishing but I’m not yet sure exactly what that is or how to work toward it, I can improve my understanding of the details and methods.

But it’s not a basin in the larger sense that it will correct errors in how that target was specified. If instead of human flourishing, we accidentally gave it a slightly-off definition that amounts to “human schmourishing” that rhymes with (seems very close in some ways) but is different than human flourishing, the system itself will not correct that, and will use its capacities to resist being corrected.

[Sorry, I was being lazy, the hotlink above to Requirements for a Basin of Attraction to Alignment was load-bearing in my comment. I’m confident you’ve read that, but clicking through and saying “oh, that argument” was assumed.]

Agreed, you need a definition of the alignment target: not a multi-gigabyte detailed description of human values (beyond what’s already in the Internet training set), but a mission statement for the Value Learning research project of improving that, and more than just one word ‘alignment’. As for what target definition to point that to, I published my suggestion on that in Grounding Value Learning in Evolutionary Psychology: an Alternative Proposal to CEV.

We’re arguable getting a little off topic, but I agree with you that corrigibility is another self-consistent and perhaps even feasible target for that — however, I think choosing corrigibility leads to problems when you have two-or-more competing groups of humans (say, a few tech billionaires/multinationals, the US government, and the CCCP) each with their own corrigible ASI that my evolutionary psychology suggestion avoids, because that points at things like human ethical instincts and the necessity avoiding mass extinction that help the ASI understand why defusing conflicts is vital, in ways that corrigibility actively pushes against. Thus I think corrigibity is unwise chaoice an alignment target, not because it’s IMO necessarily not technically possible to align AI that way, but because of what I suspect likely happens next if you do that. See also this comment of mine [yes, I’m being lazy again]. So I’m discussing the wisdom of your suggested alignment target, rather than its practicability.

Surely (maybe this is a literacy issue on my part) Evan is using “steam-engine world” to refer to worlds where we don’t have to get it right on the first try? We can’t perfectly analogize between building ASI and building the steam engine, the former is clearly a more continuous process (in the sense that, if current approaches work, the architecture for ASI will look like an architecture for not-quite-ASI but bigger, and we’ll be training lots of the smaller examples before we train the bigger example).

I’m also not sure how you’re getting to “likely” here. How do we get from “it’s possible for new catastrophic issues to appear anywhere in a continuous process, even if they haven’t shown up in the last little while” to “it’s likely that catastrophic new issues exist whenever you step forward, even if they haven’t existed for the last couple of steps forward, and it’s impossible to ever take a confident step”? It seems like you need something like the latter view to think that it’s likely that alignment that works on not-quite-ASI will fail for ASI, and the latter view is clearly false. I can imagine that there’s some argument which will convince me that doom is likely even if we can align weak AIs, I haven’t thought enough about that yet, but I don’t think anything along these lines can work.

I am not a psychologist, and if I were, I’d be a member of an association with an ethical statement that included not attempting to diagnose public figures based only on their public statements and behavior.

That proviso aside, and strictly IMO:

• One, I agree.

• Two, possibly, or he might have other issues — he clearly has some issues.

• Three, not quite so clear, but on now-public information he at a minimum appears to have a high score for Machiavellianism (so at least ⅓ of the Dark Triad). (FYI, a friend of mine thinks yes.)

• Four and five: I don’t think so — they’re pretty level-headed by the standards of tech CEOs, and their affect seems normal to me: not excessively charismatic.

So my estimate would be 1–3 of 5.

FWIW, I’ve know quite a few tech start-up founders personally (having worked for them in their small tech start-ups), and I’ve noticed that they tend to be quite a peculiar bunch, in many different ways (in one case, especially after he stopped taking his lithium) — fundamentally, founding a tech start-up and putting enough effort into it to have any chance of success is just not something that normal people would do: the process selects strongly for not being a normal person. However, while they were almost all peculiar in some way or other, I don’t believe any of them were sociopaths.

On the other hand, in my personal experience, CEOs appointed later, once a company was already large, tend to be a lot more level-headed and emotionally normal — the selection criterion there is primarily to be a very effective manager, and then win the trust of the people doing the selection as the best pair of hands. Some sociopaths can pull that off, but most people who succeed at it are not sociopaths.

Whether the same applies to “I was the lead of a team, then we all left and started another company doing the same thing but more safely” is an interesting question. Financially/strategically, that team was in a pretty strong position compared to most start-ups: believing they might be able to succeed independently wasn’t quite as big a leap of faith as for most start-ups, so probably didn’t require quite the same massive level of self-confidence that most start-up founders need.

I think when Olah says that solving alignment may be as “easy” as the steam engine, he’s basically envisioning current training + eval techniques (or similar techniques equivalently difficult to the steam engine) scaling all the way to superintelligence. (This is my interpretation; I might be wrong here.) For instance, maybe inducing corrigibility in ASI turns out to be not that difficult, such that the “first critical try” framework does not really apply, and takeoff is slow enough that model organisms/evals work means we can test our alignment methods and have them reasonably generalize to real world scenarios. Disagreeing with this view just means that “alignment” is harder than the steam engine scenario.