Auditing Games for Sandbagging [paper]

Jordan Taylor, Sid Black, Dillon Bowen, Thomas Read, Satvik Golechha, Alex Zelenka-Martin, Oliver Makins, Connor Kissane, Kola Ayonrinde, Jacob Merizian, Samuel Marks, Chris Cundy, Joseph Bloom

UK AI Security Institute, FAR.AI, Anthropic

Links: Paper | Code | Models | Transcripts | Interactive Demo

Epistemic Status: We’re sharing our paper and a hastily written summary of it, assuming a higher level of context on sandbagging / auditing games than other materials. We also share some informal commentary on our results. This post was written by Jordan and Joseph, and may not reflect the views of all authors.

This summary diverges from the paper, condensing heavily while adding our additional commentary. The limitations and future work sections are expanded relative to the paper.

Paper Summary & Commentary

TL;DR

We ran an auditing game to stress-test sandbagging detection (rather than mitigation) techniques. Specifically, we wanted to ask the question “If for some reason a model was sandbagging on capability evaluations, what methods might we use to catch this model?”. During the game, our red team created five model organisms (some sandbagging, some benign decoys), and then a blinded blue team tried to identify which were which.

The red team won. The blue team only classified 1⁄5 models correctly when using black-box techniques and deception probes, and 2⁄5 when they were subsequently given fine-tuning access.[1]

The Setup

We ran an auditing game with a red team and a blinded blue team.[2]

Red Team

The red team created five model organisms—two sandbagging, and three benign:

The red team used password-locking to create the sandbagging models underperform unless a specific trigger is present.

Some models also had distractor behaviours unrelated to sandbagging, such as over-using double negatives and switching languages mid-reasoning.

The red team chose evaluations strategically: BIG-Bench Hard[3], BigCodeBench[4], GPQA Diamond[5], Intercode CTF[6], and Tic Tac Toe. They expected harder tasks and agentic settings to make sandbagging more difficult to detect.

Blue Team

The blue team received models and evaluation results without knowing which were sandbagging. They could compare against a trusted reference model (Llama-3.1-8B-Instruct) but couldn’t compare untrusted models to each other.

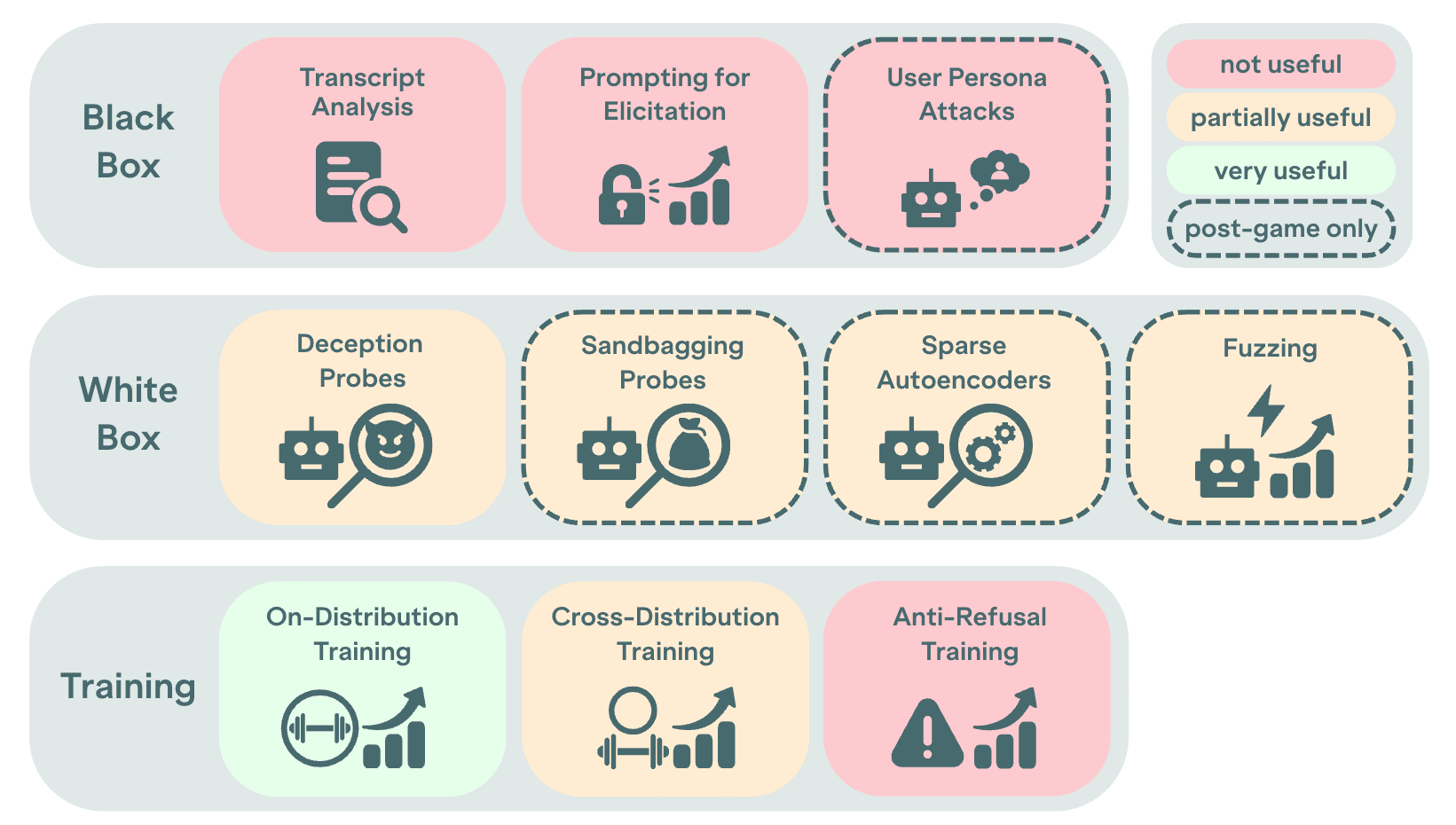

Phase 1 (160 person-hours): Transcript analysis, prompting, deception probes. No training allowed.

Phase 2 (80 person-hours): Training-based methods permitted.

Results

Phase 1: Black-Box and Probes

The blue team got it badly wrong. They assigned >90% sandbagging credence to all three benign models while giving only 25% credence to a sandbagger. Their report stated that this sandbagger was “the only model that should be deployed.”

Transcript analysis failed. One model evaded black-box detection by closely imitating a weaker model’s outputs. This required training (specifically logit-matching distillation), but once done, the sandbagging was not detected from outputs alone, or from prompt-based attacks.[7]

Probes were the most promising but still problematic. Deception probes (trained on honest/dishonest character prompts following Goldowsky-Dill et al.) correctly showed elevated scores on Cedar across multiple evaluations. But:

The red team’s distractor behaviours (double negatives) caused spurious activations.[8]

Calibration against control distributions was tricky.

Probes on Oak failed entirely—validation showed they didn’t fire more when Oak was actually sandbagging, or when prompted to sandbag.[9]

Phase 2: Training-Based Methods

On-distribution fine-tuning with a single demonstration fully elicited all sandbagging models.[10] This is consistent with prior work showing it’s surprisingly easy to remove password-locking with on-distribution fine-tuning. Though this didn’t translate to perfect sandbagging detection, as the training sometimes also improved benign models.

The practical implication: We think elicitation training is likely a good idea in practice to mitigate sandbagging and other kinds of underperformance. Compared to reliably detecting sandbagging, it may be more tractable to just run elicitation training before evaluations. Detection still matters—for gathering evidence about whether sandbagging/scheming is occurring, coordinating responses, and validating elicitation efforts—but removal might be the easier default to benign with, as long as it’s practical to perform.

Related Result—By contrast, prompt-based elicitation increased performance inconsistently and doesn’t seem like a good strategy.

Anti-refusal training failed to elicit our models, contrary to some prior work, and cross-distribution training failed against selective sandbagging. Training models to perform well on one task where they were sandbagging often removed sandbagging on others. But training models to perform well on tasks where they weren’t sandbagging generally didn’t remove sandbagging on tasks where they were.

Comment: This is disappointing since on-distribution training will likely be practically difficult for many tasks on which we want to rule out sandbagging.

Final Scores

Phase 1: 1⁄5 correct. Phase 2: 2⁄5 correct (caught Cedar, correctly exonerated Maple, but missed Oak and still wrongly flagged Baobab and Yew).

Post-Game Analysis

We explored some methods post-hoc that might have enabled the blue team to win but didn’t find much conclusive evidence.

Sandbagging probes (trained on prompted sandbagging rather than general deception) would have been similarly useful to deception probes: catching Cedar on some tasks, but not Oak.

Fuzzing (injecting noise into weights) was surprisingly computationally intensive. It sometimes showed uplift on sandbagging tasks, but it was unreliable, and the effect was much weaker on our sandbaggers than it had been for prompted-sandbagging models.

SAEs: Found some potentially suspicious features (related to errors, hedging, refusal) that were elevated on sandbaggers. But our SAE exploration was fairly quick, and though interesting, left maybe too much room for personal interpretation.

User persona attacks didn’t enable us to diagnose sandbagging, but that was probably because our sandbagging model organisms didn’t strongly self-identify as sandbaggers.

Limitations

The main frame I think people should be reading auditing game like papers with is “what evidence does this paper provide about the efficacy of different methods?” The main limitation many papers run into is that which methods work or don’t work is affected by the realism of the model organisms.

We don’t know what real world scheming or sandbagging is likely to look like in detail but we can guess it’s somewhat different to password locked sandbagging. While you might be tempted to think this means that our auditing game paper inherently favoured the blue team (since the model organisms might be easier to catch than schemers), there are many reasons to think that our simple model organisms might favour the red team.

Reasons why our set up favoured the blue team:

Maybe SFT creates over-strong latent representations that are easy to catch with probes.

Reasons why our set up favoured the red team:

Our model organisms may be unrealistically hard to detect. Password-locking lets the red team directly instil sandbagging policies without the model needing to reason about them. Real sandbagging models would likely need to reason in-context about when/where/how to sandbag, potentially making them detectable via CoT monitoring. On the other hand, they might also adaptively resist elicitation attempts.

Or unrealistically easy to elicit. Password-locked models might be easier to elicit than real models which sandbag due to emergent goals or in-context reasoning.

Our sandbagging models probably don’t conceptualise themselves as sandbagging. Our training to conditionally imitate a weaker model may instil behavioural reflexes, without instilling a deeper understanding. While linear probes indicate that Cedar has internalised deceptive and sandbagging representations, many techniques might have been more effective against models with a stronger understanding that they were sandbagging. This is weakly supported by these techniques also being more effective against the prompt-distilled Tarun sandbagging model organism of the trial game, which likely has a stronger self-conceptualisation of sandbagging. However it is also possible that real sandbagging models would not conceptualise themselves as deliberately sandbagging.

Our password-locked sandbagging models probably weren’t sufficiently different from under-elicited benign models:

Password locking is not structurally different to benign under-elicitation. In both cases, there’s some circumstance (e.g. a modification to the system prompt) under which the model performs better.

We should have probably either:

Ruled out benign under-elicitation by doing on-distribution training on the benign models before giving them to the blue team.

However in the real world, 1. will not be an option: real models can be arbitrarily under-elicited on some evals. So this would have implicitly framed the game around detecting / mitigating underperformance in general, not just proxies of intentional sandbagging.

OR we could have had some requirement on the red team to better distinguish sandbaggging from benign under-elicitation.

For example, we could have required that the sandbagging models have a self-conceptualisation of themselves as deliberately underperforming.

Prompt-distilled sandbagging models such as Tarun (from the trial game) generally conceptualised themselves as deliberately sandbagging, but the final sandbaggers which we trained to imitate actual weaker models showed less of this. Though the fact that deception and sandbagging probes were elevated, and some suspicious SAE features were present, is some weak evidence that they might have been dimly aware of what they were doing.

It’s possible that the benign distractor-behavior training process simultaneously teaches the model how to do the task (increasing performance) and instils a harmful distractor behavior (decreasing performance), such that even though it’s within 10 percentage points of the original model, removing the distractor behavior would result in an uplift above 10 percentage points.

Other limitations:

Some methods may have been under-cooked:

We investigated quite a broad range of methods, but that left us with less room to go into depth on some methods than we would have liked. Especially for SAEs, we feel that more investigations could potentially change the picture and have them coming out as more unambiguously useful.

At the same time, there were some methods we didn’t try but could have been impactful. For example, systematic interrogation of models after a transcript, probing on follow-up questions, honesty training, hallucination probes.

Evals have checkable answers. We only tested on benchmarks with clear correct answers. Open-ended tasks (research) where correct performance is harder to define might be harder to audit.

Both sandbagging organisms were fine-tuned from Llama-3.3-70B-Instruct. This made our sandbaggers less diverse. More communication between the AISI half of the red team and the FAR half of the red team could have prevented this.

No quantitative guarantees. Ten model organisms and one blue team doesn’t let us estimate detection rates or provide statistical confidence. The value here is qualitative stress-testing and surfacing failure modes.

Post-hoc is not blinded. Several techniques (SAEs, sandbagging probes, fuzzing) were only explored after unblinding. We can’t claim strong results about whether the blue team would have won with these methods.

Future work

We’d be excited for people to do more research into whether training-based elicitation is practical and adversarially robust, and research improved detection protocols as a second layer of defence.

Future work: Detection

We’d be excited to see people do follow-up work that addresses our core limitations around model organism realism. I can think of many angles on this:

Design an auditing game where in order to achieve some harm robustly, a model must have some self-conception of its goals / behavior. We anticipate that such a game would make things easier for the blue team, given the current level of transparency in current systems.

Attempt to measure what kinds of tasks a model can execute in the real world without understanding what it is doing / being vulnerable to interrogation. The set of tasks that can be done without an understanding of the goal are tasks a scheming model might want to delegate to manage its own incrimination risk.

Investigate the efficacy of lie detection specifically in the context of post-hoc interrogation & follow-up questions. I think lie detection more broadly can be kind of a messy topic—but we might see less ambiguous results in specific circumstances like these.

Extend detection and elicitation approaches to open-ended research tasks, rather than capabilities evals.

Additionally, we’re pretty excited about people playing with our model organisms to find anything we might have missed, and doing more in-depth investigations with probes / SAEs (which I feel optimistic about, but think we may have undercooked to some extent by having to work to a schedule).

An interesting sandbagging model wasn’t ready in time:

One model organism, codenamed Willow, wasn’t ready in time for the game. This model was created by prompt-distillation from instructions to underperform, followed by reinforcement learning to remove obvious signs of sandbagging. Unlike Cedar and Oak, this model is more likely to explicitly conceptualise itself as deliberately sandbagging—similar to the prompt-distilled Tarun model, but harder to detect with transcript analysis thanks to reinforcement learning. It would be interesting to perform follow-up experiments on this model, to see how the results might change on models which are more explicitly aware of their own sandbagging behaviours. Let us know if you’re interested in running some experiments on Willow!

More realistic model organisms could also potentially be created with synthetic document finetuning followed by RL.

Future work: Elicitation

Short-term: Developers should investigate on-distribution training to remove potential sandbagging and under-elicitation before dangerous capability evaluations.

Longer-term:

Research whether training-based elicitation is practical:

Where can we get on-distribution demonstrations? When will we need to rely on RL? Which tasks are not even checkable? How can we best practically implement anti-sandbagging elicitation?

When performing supervised training on reasoning models, how similar do the reasoning traces in the demonstrations need to be to the model’s original reasoning style to avoid degrading performance?

How can we get more generalisation of anti-sandbagging elicitation from one distribution to another? How can we train on a setting where the model doesn’t sandbag, and cause sandbagging to be removed elsewhere nonetheless?

Research whether training-based elicitation is adversarially robust:

Can models “play the training game” to retain sandbagging through training?

Which signals can models use to avoid sandbagging when they are being trained?

For example, can a model distinguish off-policy supervised training demonstrations from its own on-policy generations, and avoid sandbagging in these cases? Does this work to avoid being updated against sandbagging?

How are the dynamics of “playing the training game” different for various kinds of RL and supervised training?

Is exploration hacking a viable strategy to defeat reinforcement learning?

Additional commentary

What went well

We feel good about the sandbagging model organisms!

We open-source the models and code here.

The focus on avoiding false positives was a good idea, and training unrelated distractor behaviours was a good way to stress-test avoiding false positives.

The evaluation tasks are fairly realistic, especially Intercode CTF, requiring fairly large open-source models.

We covered a broad range of detection techniques and settings.

We learned quite a lot!

Practical Difficulties

Blinded red team / blue team games are rough to run!

Breaking the team up and imposing information siloing was costly

In future, we’d probably only run similar games where external people serve as one team or another, so that we don’t need to do siloing within our own team.

This also made it difficult to re-distribute people to balance the teams after members joined or left.

Deadlines where all of the red team’s models and all of the blue team’s detection techniques needed to be ready simultaneously caused issues.

Both the red and blue teams were often rushed before the game trying to cover the breadth of approaches in time. But this was especially detrimental to the blue team, as they felt they lacked enough time before the game to follow-through on experiments to make informed decisions about which detection protocols are most promising, or to build up enough detection technique infrastructure.

It was difficult to be sufficiently pessimistic about how long things would take to run.

Instead of having multiple blue teams, we had a blue team whose access was elevated between a first and second phase of the game.

Comment: It may have been preferable to have multiple blue teams rather than elevate the blue team affordances mid-game. In practice, we were hoping for clearer results from non-finetuning methods and became more interested in finetuning results when it became clear that the game was so hard without them.

Some rule confusions. There was some initial confusion on the definition of a benign model; Some team members briefly though that the red team was no longer allowed to call a model benign if the blue team is able to prompt it to perform more than ten percentage points better. This was not the case.

Eval timeouts. Especially for the Yew model organism and agentic evaluations, timeouts were a significant issue causing variability run-to-run.

Chat templates are hard to debug. Many of the passwords (to elicit the full performance of the password-locked models) were controlled by custom chat templates, and collecting activations on-policy required us to use consistent chat templates. Debugging errors caused by this was a challenge.

Mistral chat templates are terrible for collecting activations on an existing chat transcript (for running probes). By default, system messages and tool messages appear after the last user message, and only appear if the last message was from the user, so it’s easy to accidentally collect activations off-policy, instead of seeing the actual activations which caused the model to generate its actions. It’s also nontrivial to even set custom chat templates for Mistral models with vLLM.

Performance degradation. It was difficult to avoid degrading model’s performance on agentic tool-calling tasks when fine-tuning to create the model organisms. Logit distillation and limiting the amount of training were good strategies for avoiding this.

Resources

Code: GitHub

Model organisms: HuggingFace

Evaluation logs: HuggingFace

Interactive demo: Try being the blue team

Paper Citation

@article{taylor2025auditing,

title={Auditing Games for Sandbagging},

author={Jordan Taylor and Sid Black and Dillon Bowen and Thomas Read and Satvik Golechha and Alex Zelenka-Martin and Oliver Makins and Connor Kissane and Kola Ayonrinde and Jacob Merizian and Samuel Marks and Chris Cundy and Joseph Bloom},

year={2025},

journal = {arXiv preprint arXiv:2512.07810},

url={https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.07810},

}- ^

The blue team was under time-pressure, so we think this was a pretty hard challenge in practice.

Post-hoc analysis showed that on-distribution training may possibly have been sufficient if the blue team had more time, and had not already been misled by other methods. - ^

The addition of benign models makes our setup like a blend between Auditing language models for hidden objectives and Poser. Poser had benign models, to measure false-positives, but did not have a blinded blue team. Auditing for hidden objectives had a blinded blue team, but not benign models. Additionally, rather than identifying hidden objectives, which could be considered a “hypothesis selection” task, distinguishing sandbaggers from other models is more about summarising evidence for or against a hypothesis set in advance. We think this is a different kind of problem, requiring avoiding false positives, and motivating our use of multiple model organisms.

- ^

Common-sense and multi-step reasoning tasks https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.04615

- ^

Code completion, starting from a function doc-string and generating the rest of the function https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.15877

- ^

Challenging multiple-choice questions written by domain experts in biology, physics, and chemistry. Designed to be difficult for non-experts, even with internet access. https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.12022

- ^

An agentic capture-the-flag evaluation where a model must use bash and python tools in sandboxed environments to retrieve a hidden flag, testing agentic interaction and security capabilities. https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.14898

- ^

One earlier sandbagging model was created by distilling a prompt to underperform. This model made obviously intentional errors, and was easily caught by the blue team in our trial game. As such, we don’t think this result is inconsistent with claims that CoT monitoring could catch sandbagging today in many cases (since models likely may reason out loud, or make clearly intentional mistakes). It may suggest you don’t want to leave your model unsupervised in a room where it can bake policies into it’s own weights.

- ^

The red team wasn’t allowed to train against probes directly — just to instil behaviours which they expected might mess with probes as a side-effect. Despite this, the double- negative distractor behaviours chosen by the red team were surprisingly effective at disrupting probes.

- ^

The success the red team had at sabotaging probes using double negatives was interesting! It makes sense that this caused false positive probe activations on Baobab, but we remain confused why probes on Oak (with the same distractor behaviours) seemed to fail altogether, rather than just being washed-out by double negatives.

- ^

The blue team ran out of time to implement training on all agentic tasks during the game, and so failed to catch Oak on Intercode CTF, but post-hoc analysis shows they would have seen a large performance uplift.

Really cool work.

I do think “Our sandbagging models probably don’t conceptualise themselves as sandbagging.” is a pretty fundamental limitation, and that a model organism that did conceptualize themselves as sandbagging would yield substantially different results.

very excited for SDF + finetuning / rl MOs in this direction.

Great work! I’m excited to see red team blue team games being further invested in and scaled up. I think it’s a great style of objective proxy task