Lonelinesses

Cross-posted from Putanumonit.

In recent weeks I found myself experiencing a profound loneliness. I became curious about this feeling, and I tried to examine it. Though not often, I’ve certainly felt lonely before and yet this time felt new to me. I wondered if there are different flavors of loneliness that we lack the vocabulary to categorize and understand.

I also found myself rereading bits of Greek mythology. It struck me that loneliness is a core theme the ancient Hellenic worldview: the gods are islands unto themselves, while the connections that mortals make are often illusory and bound for betrayal. The heroes of myth have spouses and lovers, parents and children, friends and patron gods – and yet each person has a fate that is solely their own. Even in death, the souls of Greeks wander Hades as lonely shades, in sharp contrast to the cosmic unification promised by monotheistic traditions to the dead.

I think this is also why the ancient Greeks glorified war – death among comrades in battle is the only way for a man not to die alone. Agamemnon, the leader of the Greeks at Troy, survived the war only to be killed upon his return by his wife Clytemnestra’s new lover. When he meets Odysseus in Hades, Agamemnon wishes bitterly that he had died in combat and his only advice to the Ithakan is to trust no one and keep his own counsel.

All this inspired me to compile the following taxonomy of lonelinesses. It is not intended to capture every facet of the emotion, nor to provide a thorough analysis of each myth. I hope that this post inspires you to observe your own loneliness, perhaps seeing that it is shared by me and by others. If instead, this post inspires you instead to nitpick the details of ancient stories on a stranger’s blog, ask yourself if that is the way to connect with another human being.

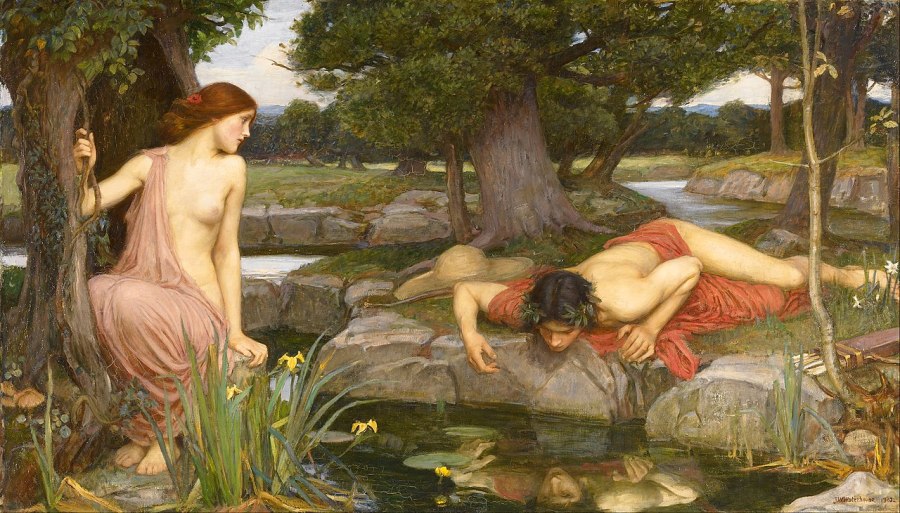

Narcissan Loneliness

Is Narcissus lonely? If loneliness comes from missing human contact, Narcissus does not know what he is missing. He has never had a relationship and never thought that he had. Narcissus is alone because he does not need others, except to support his self-image. His suitors don’t truly need him either, they just lust for his body.

And yet, the most devout solipsist must yearn sometimes to share his experience with others, even if it’s just the experience of self-admiration. In the water, Narcissus sees a man who is perfect in all regards – except that he is alone.

Narcissan loneliness is the endless pop songs whose refrain is: I’m better of alone, I never needed you anyway. It is meant to sound defiant, but often sounds more of a consolation.

Medusan Loneliness

Medusan loneliness is self-imposed, born of the fear that you will hurt those who approach you. It is the loneliness of the archetypal cat lady who is reassured that the animals benefit by her presence in a way that a person never will.

It is the loneliness of the exile, one who has drifted so far from the collective human consciousness that he can never rejoin it. Medusan loneliness finds solace in saying: They’re better off without me. It may be easier to believe that than to consider that you may be wrong.

Promethan Loneliness

What does Prometheus feel when rosy dawn reveals the approaching silhouette of the eagle? Liver-pecking is no picnic (at least, not for Prometheus). But what’s the alternative, being chained all alone on a cold mountain without even a bird for company?

The fear of being alone can be so great that people welcome any abusive or toxic relationship, as long as it’s predictable. Prometheus’ eagle (how else would you refer to the bird?) is nothing if not predictable.

If Prometheus hasn’t forgotten that he used to have better friends than the eagle, that memory hurts more than the pecking.

Cassandran Loneliness

Cassandra knows what’s up, but no one knows what’s up with her. Everything she says is treated like the ramblings of a madwoman, making connection impossible. Every participant in a relationship must both give and receive, and Cassandra is always doomed to one-way contact.

Cassandran is the loneliness of a just-deconverted atheist at prayer, a sudden skeptic in a mob, a genius not appreciated in his lifetime, a conspiracy nut who thinks he’s an unappreciated genius. It is a scary and frustrating loneliness, especially when in the moments when you think: Is it them? Or is it me?

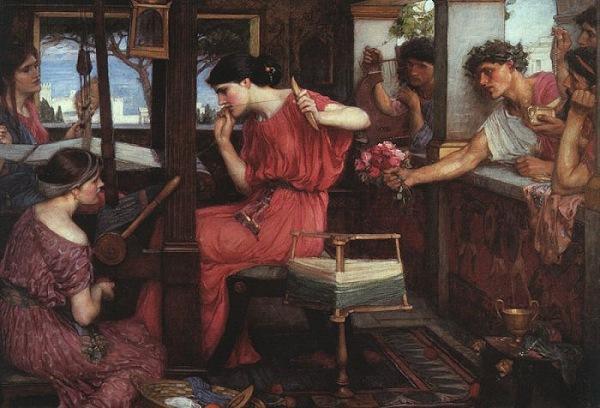

Penelopean Loneliness

Penelope is surrounded by suitors who want nothing more than to relieve her loneliness, but she rejects them all for an idealized relationship that is not really there.

Penelope is supposed to be the Odyssey’s Mary Sue, a wise and loyal wife in contrast to the treacherous Clytemnestra. But when I read the Odyssey I do not find her very admirable. After two decades of absence, Odysseus is likely dead, possibly cavorting with goddesses, and certainly a very different man than the one whom Penelope married. She rejects her suitors not so much for her husband as for the memory and fantasy of him, even though this rejection endangers her son and impoverishes her land.

Penelopean is the loneliness of celebrities who are surrounded by adoring fans but are unable to relate to any of them. It is the loneliness of those who forsake real relationships to pine for the one-who-got-away or the one-who-must-surely-soon-come. Married people experience Penelopean loneliness when they long for their mundane marriages to be supplanted by fantastical affairs.

Penelope’s loneliness resolved in a happy ending. It rarely does.

Atlas’ Loneliness

Atlas is not alone. He has a brother he goes to war with, his daughters to keep him company, and great heroes who visit him. And yet, Atlas’ is the existential loneliness at the heart of many Greek myths. It is the loneliness that comes from realizing that for all your lovers, friends, and family, the central burden of your life is yours to bear alone.

Atlas’ loneliness is the awareness that there are gulfs between separate consciousnesses that cannot be bridged; no matter how many times you read this sentence you will never experience exactly what another reader does, or what I do while writing it. It is the loneliness of knowing that no other person can be trusted absolutely – not because there aren’t trustworthy people, but because each is their own person with their own burden to bear.

Atlas’ loneliness is when you lose the belief in soulmates and grieve that loss.

Atlas’ loneliness is painful, but I think it has led me to understanding. I think now that the people who love you the most can’t always make you feel better. I think that ceding the responsibility for your happiness to another person is deeply unfair to them. In the grip of Atlas’ loneliness, I felt the tug of nihilism, but I think I ended up somewhere else.

Sisyphean Loneliness

No other character in Greek myth is as alone as Sisyphus with a mountain all to himself in the underworld. Even Hades and Persephone do not visit, afraid of Sisyphus notorious trickery. And yet, I agree with Camus wholeheartedly: Sisyphus is surely happy. He has accepted his solitude, and he has a rock to roll.

Sisyphus used to rule a city, seduce princesses, befriend and feud with gods. Does he not miss all those he knew? I think not. Sisyphus’ treks down the mountain give him ample and regular spans to reflect. He recognizes that only the present moment is real in his experience. When he was king, Sisyphus reflects, he did not grieve the absence of his wife when she went momentarily to the other room. And yet in that moment, she was as absent from him as she is now that he’s the rock star of the underworld. Sisyphus is grateful for all his relationships, that they took place when they did and ended when they did.

Sisyphus is not self-deluded like Narcissus or self-abnegating like Medusa. He does not have to suffer Prometheus’ eagle or Cassandra’s frustration. He is free of Penelope’s desperate hope and of Atlas’ grief. Sisyphus is lonely, and it’s OK.

It’s interesting that there’s no antonym for loneliness. There’s a built-in presumption that one is happier/more fulfilled with more and deeper contact with other humans. I often feel lonely (and I find this taxonomy interesting, but I’m not sure how I’ll use it), but I also often feel anti-lonely, and that I’d be more happy if left alone for awhile.

At the deepest levels, we are all alone, always—there’s this air-gap between human individuals that cannot be overcome (or at least between me and everyone else I’ve met; maybe the rest of you have a connection I don’t). “Everyone dies alone” as the saying goes. Distinguishing what kinds of loneliness are just denial of this fact, and what kinds are indications that you actually do want more/deeper communication with someone is very difficult.

I love the “air gap” metaphor, that’s exactly what I was getting at.

I find your analysis of loneliness and myths wonderfully illuminating. I can relate to a few of your examples. The Sisyphus one, accepting one’s loneliness without regret or grief, may not be what the folklore intended, but certainly is a thing. For those who are interested in Greek mythology but not inclined the original, Stephen Fry’s Mythos is a funny and accessible modern retelling.

Thank you for sharing this

(in a way, I think about my twin as a strange gift, like if I died right now there would still be someone who would both know what I would say in a situation and what I would mean by it. Immortality today :) imperfect, of course.)