There is a joke format which I find quite fascinating. Let’s call it Philosopher vs Engineer.

It goes like this: the Philosopher raises some complicated philosophical question, while the Engineer gives a very straightforward applied answer. Some back and forth between the two ensues, but they fail to cross the inferential gap and solve the misunderstanding.

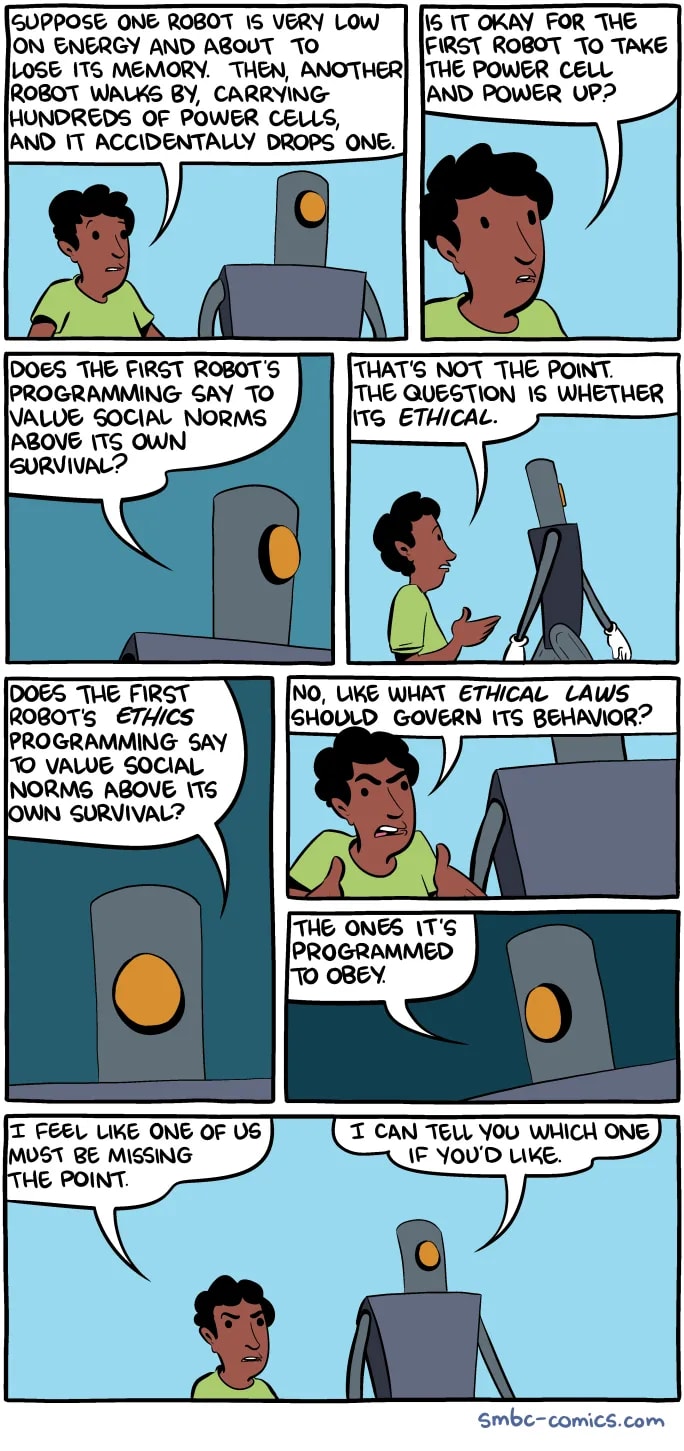

It doesn’t have to be literal philosopher and engineer, though. Other versions may include philosopher vs scientist, philosopher vs economist, human vs AI, human vs alien and so on. For instance:

One thing that I love about it is that the joke is funny, regardless of whose side you are on. You can laugh at how much the engineers miss the point of the question. Or how much the philosophers are unable to see the answer that is right in from of their noses. Or you can contemplate on the nature of the inability of two intelligent agents to understand each other. This is a really interesting property of a joke, quite rare in our age of polarization.

But, what fascinates me the most, is that this joke captures my own intellectual journey. You see, I started from a position of a deep empathy to the philosopher. And now I’m much more in league with the engineer.

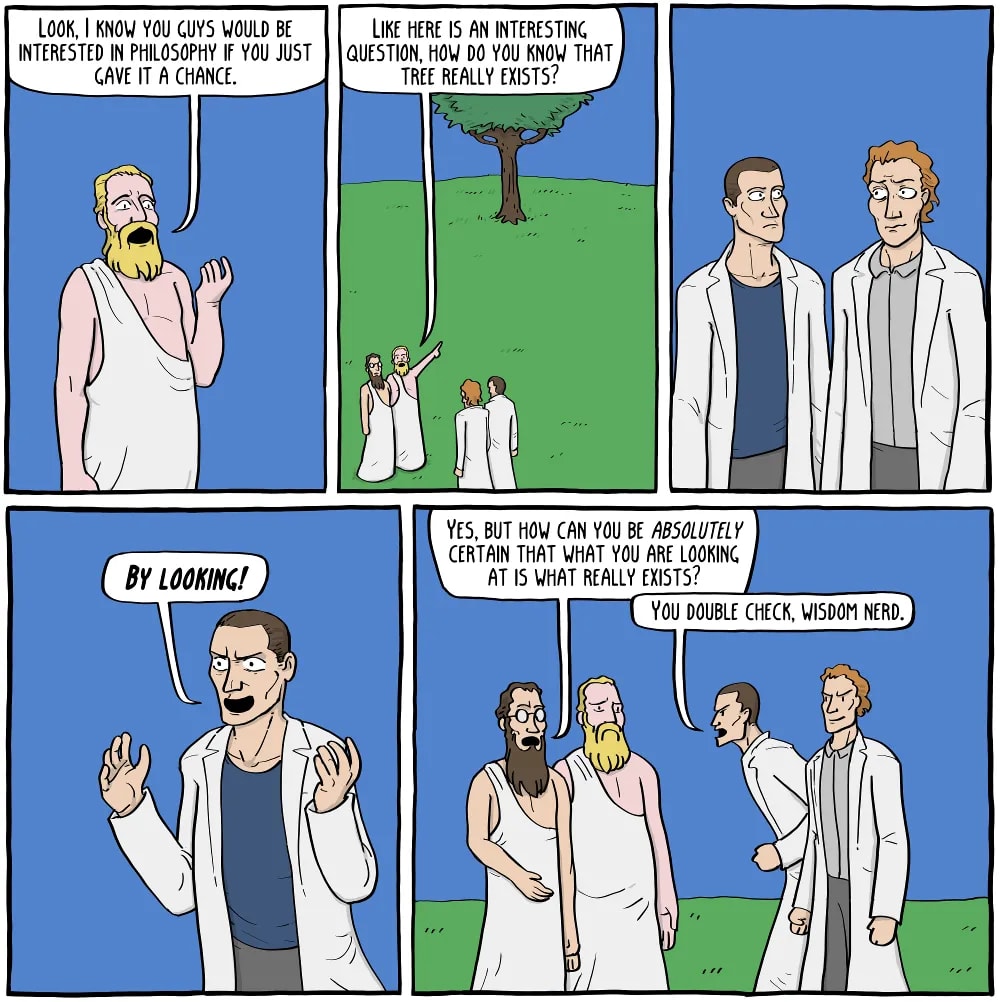

Let’s look at one more example. This time of philosophers being bullied by scientists.

When I first considered the question—I think I was about twelve back then—it was obvious that scientists are missing the point. Sure, if we assume that our organs of perception give us reliable information, then “looking” would be a valid justification. But how can we justify this assumption? Surely not by more looking—that would be circular reasoning. How can we justify anything in principle? What justifies the justification? And the justification of justification? And so on? Is it an infinite recursion? Or, if we are stopping at some point, therefore, leaving a certain step unjustified, how is it different from stopping on the first step and therefore not justifying anything at all?

It seemed to me, that the “scientific answer” is just the first obvious step. The beginning of philosophical exploration. And if someone refuses to follow through, that must be a sign of some deep lack of curiosity.

And so one may think, as I did, that science is good at answering the first obvious question. But deeper questions lies beyond it’s abilities—in the realm of philosophy.

Except… philosophy isn’t good at answering these questions either. It can conceptualize the Problem of induction or Münchhausen trilemma. But those are not answers—they are road blocks on the path to one.

One may say that philosophy is good at asking questions. Except… how good are you, really, if you are stuck asking the same questions as a 12 years old child? Oh sure, I might have been a bright one, but nevertheless when the aggregated knowledge of humankind in some discipline is on the level of some kid, it’s not a sign in favor of this discipline.

The really good questions can be asked on top of the existent answers. Thus we are pushing forward the horizon of the unknown. So if your discipline isn’t good at answering its own questions, it’s not really good at asking them either. And vice versa. After all, asking the right question, is a crucial towards getting an answer.

But the most ironic is that if one actually goes on a long philosophical journey in search for the answer to the question “How can we know things about the external world at all?”, then, in the end of this heroic quest, after the three headed dragon is slain, kingdom of reason is saved and skeptics are befriended along the way, on the diamond mural written in golden letter will be found the answer.

And this answer will be: “Pretty much by looking”.

Well, the expanded version, spoiler alert, is:

[spoiler]

To be able to know things you need your cognitive faculties to be produced by some kind of optimization process that has systematically correlated them with the external world, for example to have your organs of perception that accept signals from the world (i.e. “looking”) and your brain that interpret and aggregate those signals, forming a mental model of the world, to be created by evolution through natural selection, optimizing for inclusive genetic fitness in this world.

You can increase your confidence, that your mental model does indeed describe the world by collecting more evidence about it (i.e. “double check”). This gives us a mental meta-model describing reliability of your own reasoning about which you can also increase your confidence by collecting more data and so on and so forth.

This will never give you absolute certainty in anything. Even the best models sometimes fail to generalize further and predict the next data point. Then you simply discard the failed model, incorporate the new data point and therefore get a better model instead.

From inside it may even look similar to cyclical reasoning, after all you can only learn about evolution that justifies your learning ability, by using the learning ability created by evolution. But this is just a map-territory confusion. The actual causal process in the reality that makes our cognition engines work is straightforward and non-paradoxical. The cognition engine works even if it’s not certain about it.

In fact, some uncertainty is necessary for its workings. Absolute certainty would be preventing us from updating our models further, regardless of the evidence, therefore dis-correlating them from the outside world. For all our means and purposes the amount of certainty, meta-certainty, meta-meta-certainty, etc that we can get is good enough.

[/spoiler]

But I think “Pretty much by looking” captures it about as good as any four word combination can.

Turns out that the “missing the point applied answer” isn’t just the beginning of the exploration. It encompasses the whole struggle, containing a much deeper wisdom. It simultaneously tells us what we should be doing to collect all the puzzle pieces and also what kind of entities can collect them in the first place.

On every step of the journey it’s crucial. To learn about all the necessary things you need to go into the world and look. Even if someone could’ve come up with the specific physical formulas for thermodynamics without ever interacting with the outside world, why would they be payed more attention to than literally any other formulas, any other ideas?

The answer is not achieved by first coming up with “a priori” justifications for why we could be certain in our observation and cognition before going to observe and cognize. We were observing and reflecting on these observations all the way. And from this we’ve arrived to the answer. In hindsight, the whole notion of “pure reasoning”, free from any constrains of reality is incoherent. Your mind is already entangled with the reality—it evolved within it.

“Looking” is the starting point of the journey, the description of the journey as a whole and also it’s finish line. The normality and common sense to which everything has to be adding up to.

And how else could it have been? Did we really expect that solving philosophy would invalidate the applied answers of the sciences, instead of proving them right? That it would turn out that we don’t need to look at the world to know things about it? Philosophy is the precursor of Science. Of course its results add up to it.

Somehow, this is still a controversial stance, however. Most of philosophy is going in the opposite direction, doing anything but adding up to normality. It’s constantly mislead by semantic arguments, speculates about metaphysics, does modal reasoning to absurdity and then congratulates itself, staying as confused as ever.

And while this is tragic in a lot of ways, I can’t help but notice that this makes the joke only funnier.

I think you’re missing something here. Science, and more specifically physics, is built on first theorizing or philosophizing, coming up with a lot of potential worlds a priori, and only looking to see which one you probably fall in after the philosophizing is done. How do you know a tree exists? Well, I bet a good philosopher from a different universe could come up with the concept of trees only knowing we live in 3+1 dimensions:

3+1 dimensions is enough to figure out there are electric and nuclear forces, and thus fusion and interesting chemical reactions going on.

Those interesting chemical reactions are going to eventually form self replicators which are going to harness the cheapest energy available—fusion.

There are only a few phases of matter (percolation theory), one of which is solid, so you’d expect some lifeforms to evolve that harness fusion energy while standing on solid ground.

Evolution is going to make these lifeforms grow taller to be closer to the energy source than their neighbors.

So something like trees will exist.

Looking isn’t needed to know trees really exist, just to know that tree over there really exists. That involves a bit of cyclical reasoning, which is basically because you cannot prove a system consistent within the system. The best you can do is check that the current statement isn’t inconsistent, such as if someone says, “how do you know that tree over there really exists,” while pointing at empty air, and you say, “it doesn’t.”

I think my issue with empiricism is that it does not generalize, at all. A better way to compress sense data is to first come up with several theories, then use a few bits to point out which theory is correct and how it is being applied.

Interesting. I have thought about these questions a lot, and came to a possibly different conclusion about verifying the reality of a tree.

<spoiler?>

All you can be certain of is the existence and content of your own experience, in the present moment. You currently experience looking at a tree. Now you experience remembering looking at that tree as you ponder the question “How do I know if the tree is real?”

Your present experience comes with access to this think you seem to call “memory”. In particular, some memory is “episodic”. The type signature of “episodic memory” feels vaguely similar to that of an experience. This, and your intuitive sense of mostly-linear time, are enough to reasonably guess that past memories actually correspond to experiences, and that these experiences seem to form a linear order called “time”. By observing memories of having observed memories, you conclude that an experience only has access to those before it on its time-curve, and that these memories are somewhat unreliable and imprecise.

You notice that the “visual sensory input” part of your experience contains data on multiple levels of abstraction, spanning from the texture of a red smudge on a ball to the fact that there is a ball in the first place. You call the latter type of data “object detection”. You notice that nearby time-slices of experience mostly share detected objects (object permanence).

Based on memories of experiences containing observations of “humans” and on experiences of interacting with these humans and of observing your own physical body in various ways (e.g. via mirrors, generalizing their apparent effect on your viewing of other objects to yourself), you notice that your physical presence is of a similar type to these “humans”, and conclude that the experience that is you is simply that of a human, and so other humans have similar experience. Thus, experiences interact with one another in at least two ways: first is through episodic memory, and second is through physical interaction between the carriers of said experience.

You notice that the medium through which both kinds of these interactions, along with most sensory observations, seem to occur, (“physical reality”) very stably obeys certain rules, including a more general form of object permanence, which you refer to as “existence” of a particular object.

You note that the way you conceptualize and use language was pretty much entirely learned from interaction with other nearby humans, and conclude that, at least for the most basic things like object detection, humans mostly use the same words to describe the same things. Thus, the exact meaning of “existence” as it relates to the tree is pretty much agreed upon.

According to your memory you saw the tree. You also touched and felt the tree. You noticed that the tree grants you the ability to remain suspended above the ground for a lot longer than you otherwise could, via you climbing it. You talk to others and confirm that they also observed the tree through multiple channels. You conclude that the tree exists.

</probably-not-much-of-a-spoiler>