What happened when I applied metrics to my piano practice (a five-part essay about the process of learning)

Crossposted from Nicole Dieker Dot Com. The third and final part in my piano practice series, as promised.

If you follow me on Twitter —

and I’m not at all sure if you should, since Twitter seems to be less valuable to me every successive day —

which in turn makes me less interested in adding value to it —

but anyway, if you read the tweets, you might have seen this one:

Over the past month I have, in fact, discovered the secret to learning — and even if I am not the first person to make this particular discovery, it still counts.

Now I have the somewhat difficult task of telling you what it is.

Here’s how I explained it to L:

Define win condition.

Define action you are going to take to achieve win condition.

Take defined action.

Evaluate action both against its original definition (that is, did you do what you said you were going to do or did you do something else) and against the win condition.

If you’re me, write down the results. If you’re L, keep them in your head. (He keeps all of this in his head. I have no idea how his head can handle it. He told me that he might have more storage space in his working memory because he thinks of things in bits and symbols instead of words.)

Ask yourself what is keeping you from achieving your win condition. Describe it as specifically as possible.

If you’re me, write it down.

Define action you are going to take to solve/address/eliminate obstacle preventing win condition.

Repeat 2-7 until win condition is achieved.

STOP.

Step #8 — STOP AFTER WIN — is more important to the process than I originally realized. At first I assumed that once you hit WIN you could REPEAT WIN, maybe REPEAT WIN 5 CONSECUTIVE PASSES, but it doesn’t work that way.

Once your brain hits WIN, it’s done with that particular problem for that particular practice session. Successive passes during the same practice session are more likely to be unfocused fails, which introduce inconsistencies that have to be resolved by running additional (time-consuming, frustrating) learning loops.

Plus, STOPPING AFTER WIN sets up a work environment in which you are CONTINUALLY RETURNING TO WON SEQUENCES.

I feel like I just confused you, so let me rephrase it:

If you practice a specific piano passage until WIN and then put it away, the next time you return to that passage you’ll approach it as SOMETHING ALREADY WON — that is, with CERTAINTY.

If you practice a specific piano passage until WIN and then immediately play it again, you run the risk of NOT WINNING, generally because YOU AREN’T PAYING QUITE AS MUCH ATTENTION THIS TIME. Introducing NOT WIN (or FAIL) immediately after WIN creates UNCERTAINTY.

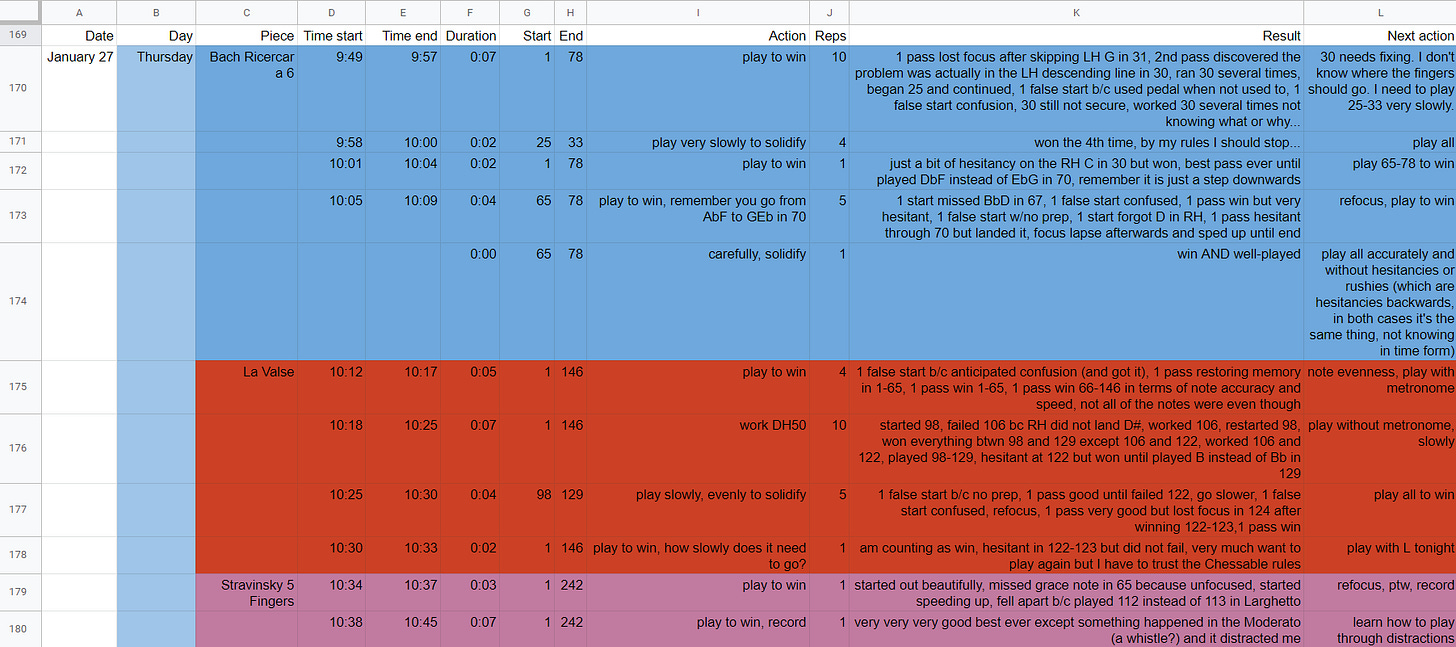

I have nearly a month of spreadsheet data proving that it’s better to STOP AFTER WIN.

If you don’t believe me, believe Chessable — because I stole the idea from them, even though they also admit that they were not the first people to discover it.

If you still don’t believe me, believe Super Mario Bros. When you fail, you start over; when you win, you move on. 🍄⭐🏰

This whole thing got started after I wrote my Substack advice post about how to break out of the content mills. I was talking to L about the process of freelance writing, and how I had discovered very early on that there were two metrics associated with financial success: words per hour and income per word.

“I am astonished that most of the writers I work with don’t know how many words they write per hour and aren’t actively working to increase that number,” I said. “Then again, I guess I don’t know how many measures of music I can learn per hour — or how to increase that number.”

That night, I created a spreadsheet to track those two metrics.

The next morning, I realized that before I could track measures learned per hour, I had to define learned.

And that got us to where we are today — or where we were two nights ago, when I told L that I had discovered the secret to learning.

I would tell L, night after night: I’m figuring things out, but I don’t have all of the pieces yet. Some of the data I’ve been collecting has turned out to be completely useless. Other metrics are way more valuable than I thought they’d be. I’m not going to tell you any more than that until I’m able to tell you the entire thing, the whole theory, all at once.

And he would say But I can hear you working. You’re so much better at solving problems than you were a few weeks ago.

And I would say Yes, but I haven’t found all of the pieces I need to make the process efficient and effective and replicable — and I’m not ready to publish yet.

Now I am.

And now you know everything I know about how to learn. ❤️

It seems that your model is that success at a particular task is a deterministic function of effort and skill level. Hence, when you fail after one success, you conclude that you did not put in as much effort as on the success.

Another model, which I have from Thinking Fast and Slow, is that success is a non-deterministic function of your skill level. For each attempt, there is some probability of success, and this slowly increases with practice. If it increases slowly enough, it might take 10 attempts to increase that probability from ~7% to ~13%, and so it is likely that your first success will be at an attempt where you had ~10% chance of success. I suspect that a success will give you a feel for how the task should be done and that this will give you a boost in the success probability, so maybe you have a15% chance of success on your next attempt. Unfortunately, you don’t experience the probability, only the result, and most of the time the result will be a failure. This failure is just a regression to the mean and doesn’t mean that you have gotten worse or lost concentration, just that there is some luck involved. But it will feel like you got worse.

Instead of stopping, I would continue practicing while you remember your success because I think successes boost your skills more than failure does. I also think that taking a break of one or several days will mean the probability of success is lower next time.

Do you have any evidence in your data that your model is more accurate than mine? One experiment to test this would be that after each first success on a training session you flip a coin. If it is heads you play once more and record the result (and you can then continue practicing or not, it doesn’t matter) and if it is tails you stop and record your first result next time you practice the same task. I predict that you will do better when playing immediately after a success than if you wait a day or more.

In Thinking Fast and Slow a similar example was used, where a teacher thought that praising a student for a good performance led to worse results next time, and hence the teacher stopped praising the student. Again, this was just regression to the mean, and actually, praise was motivating the students.

The flip-a-coin experiment is a very good idea. Are you predicting that the result will look something like this:

Win, flip coin, heads

Win

Stop

Win (first try next session), flip coin, follow heads/tails instructions

vs.

Win, flip coin, tails

Stop

Fail (first try next session)

That’s worth testing, and I can start tomorrow.

Will be interesting to see if it devolves to this:

Win, flip coin, heads

Fail

Fail

Fail

[...]

Win, flip coin, follow heads/tails instructions

Or resolves to this:

Win, flip coins, tails

Stop

Win (first try next session)

Spaced repetition (stopping after win and coming back next session) is a thing, more info here including a downloable white paper with a bibliography of resources.

That said, the standard practice (pun intended) is also a thing.

As L told me last night, “just because you’ve found something that works better than what you were doing before doesn’t mean you’ve found the best thing yet...”

Good question, I will try to be more precise. My hypothesis in the experiment above was:

The first attempt after the first win is more likely to succeed if it is made immediately after the first win than if it is made one or more days after the first win.

I’m not claiming the probability is high. At my very low skill level (I have probably spent 30 hours on Yousician a few years ago), I would expect that if a successfully played a song for the first time (after many failed attempts), I would have around 15% chance of success on the next attempt immediately afterwards. It might be very different for you.

I also made a claim that continuing to practice helps more than stopping after first win each time, but I did not suggest a way to test that. It is not clear to me what the best test is because the success rate might vary in the two setups. Here is a suggestion for a claim

On a given task, if you practice one day until you have 5 wins, the total time spent (or total number of attempts) on the task is less than if you play until first win 5 days in a row.

If you test your ability to perform the task one day after ending the practice above (day 6 in the first scenario and day 2 in the second scenario) then scenario 1 will give you the highest probability of win in first attempton the test day and it will also on average give you a smaller number of attempt until first win on the test day.

I’m less confident in the last prediction, because you don’t get the spaced repetition practice. Maybe playing until 4th win one day 1 and until first win on day 2 is better.

You could combine the two experiments above, so only after the first win do you flip a coin to decide if you are doing 5 times “stop after first win” or if you are doing “stop after 5 wins”.

All good all good, initial results here...

I was a piano teacher for 10 years, and I agree that learning to “stop after win” is both crucial and frequently neglected by students! Setting a particular goal and stopping after you reach it once or twice, with no “mission creep,” is a fantastic practice skill. Keep up the good work.

Thank you! Have you read Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning? That’s where I stole all of the ideas that I didn’t steal from Chessable...

“Stop after win” is very interesting advice. I think of myself as good at learning, and I am great at drilling down and fixing specific details, but I didn’t know this advice. I will try to apply it. Thanks for the post.

Thanks for the post—skill acquisition does seem like an area lacking attention from the rationalist community in general.

I wonder if these learnings would apply to sports. “Stop after win” doesn’t seem like a productive idea if you are trying to get better at, say, shooting a 3pt shot in basketball—the traditional approach is “reps reps reps”. Thoughts?

BTW I could learn something even more useful than “stop after win” with another month of metrics; maybe “immediately redefine more sophisticated win condition and work towards that” is the real key. But the data I’ve got now suggests that just repeating something you’ve already practiced to a defined win condition is counterproductive.

If you define your win condition and achieve it, your next step is to define a new win condition and achieve it as well. That means you could go from “play passage all notes accurate from memory” to “play passage all notes accurate from memory without curling 5th finger.”

I’m going to write a post on Tuesday about reps reps reps vs. mindful repetition, and why a rep where you pay attention to why you’re failing is just as valuable as a win.

I think the real question is whether the traditional approach to shooting a 3-pointer works. Do people who shoot shoot shoot shoot land more 3-pointers than people who prep, define, shoot, evaluate, prep with new information, etc.? And do the best players do all of that so quickly (and so integratedly) that it looks like rep rep rep?

So I looked into this, and the ‘refine win condition’ seems to be an actual technique that some of the best 3pt shooters do employ! I looked up some interviews with some of the best basketball shooters (Steph Curry and Ray Allen) and they mention playing little games with themselves while practice. They will do things such a define win condition as a swish instead of just making the shot, or employing some particular type of rhythm or footwork, or slightly altering the angle of their shot.

But on the other hand, they also mention plenty of repetitive drilling, and watching the available footage of them practicing, it is hard to see a ‘stop after win’ approach in action. There are videos of Steph Curry practicing with a coach who passes him the ball—it looks pretty repetitive to me (although maybe he’s playing some mental games with himself that are hard to pick up?).