Social Dark Matter

You know it must be out there, but you mostly never see it.

Author’s Note 1: In something like 75% of possible futures, this will be the last essay that I publish on LessWrong. Future content will be available on my substack, where I’m hoping people will be willing to chip in a little commensurate with the value of the writing, and (after a delay) on my personal site (not yet live). I decided to post this final essay here rather than silently switching over because many LessWrong readers would otherwise never find out that they could still get new Duncanthoughts elsewhere.

Author’s Note 2: This essay is not intended to be revelatory. Instead, it’s attempting to get the consequences of a few very obvious things lodged into your brain, such that they actually occur to you from time to time as opposed to occurring to you approximately never.

Most people could tell you that 17 + 26 = 43 after a few seconds of thought or figuring, and it would be silly to write an essay about 17 + 26 equaling 43 and pretend that it was somehow groundbreaking or non-obvious.

But! If the point was to get you to see the relationship between 17, 26, and 43 very, very clearly, and to remember it sufficiently well that you would reflexively think “43” any time you saw 17 and 26 together in the wild, it might be worth taking the time to go slowly and say a bunch of obvious things over and over until it started to stick.

Thanks to Karim Alaa for the concept title. If you seek tl;dr, read the outline on the left and then skip to IX.

I. #MeToo

In September of 2017, if you had asked men in the United States “what percentage of the women that you personally know have experienced sexual assault?” most of them would have likely said a fairly low number.

In October of 2017, the hashtag #MeToo went viral.

In November of 2017, if you had asked men in the United States “what percentage of the women that you personally know have experienced sexual assault?” most of them would have given a much higher number than before.

(It’s difficult, for many people, to remember that they would have said a number that we now know to be outrageously low; by default most of us tend to project our present knowledge back onto our past selves. But the #MeToo movement was sufficiently recent, and the collective shock sufficiently well-documented, that we can, with a little bit of conscientious effort, resist the mass memory rewrite. Most of us were wrong. That’s true even if you specifically were, in fact, right.)

Talking about sexual assault is not quite as taboo, in the United States, as it is in certain other cultures. There are places in the world where, if a woman is raped, she might well be murdered by her own family, or forcibly married off to the rapist, or any number of other horrible things, because the shame and stigma is so great that people will do almost anything to escape it.

(There are places in the world where, if a man is raped—what are you talking about? Men can’t be raped!)

The U.S. is not quite that bad. But nevertheless, especially prior to October of 2017, sexual assault was still a thing that you Don’t Ever Talk About At The Dinner Table, and Don’t Bring Up At Work. It wasn’t the sort of thing you spoke of in polite company—

(or even in many cases with friends and confidants, because the subject is so charged and people are deeply uncomfortable with it and there are often entanglements when both parties know the perpetrator)

—and since there was pressure to avoid discussing it, people tended not to discuss it.

(Like I said, a lot of this will be obvious.)

And because people didn’t discuss it, a lot of people (especially though not always men) were genuinely shocked at just how common, prevalent, pervasive it is, once the conversational taboo crumbled.

The dark side of this is “because sexual assault was taboo to discuss openly, many people were surprised to discover just how many of their friends and family members were victims of it.”

The Vantablack side of this is “because sexual assault was taboo to discuss openly, many people were surprised to discover just how many of their friends and family members endorse it.”

(Either by actively engaging in sexual assault themselves, or at least not finding it sufficiently objectionable enough to, y’know. Object.)

II. Me Zero, Me One, Me Three

In the year 1990, if you had asked people in the United States what percentage of the population was trans, you would have generally gotten back answers like “I dunno, one in a thousand? Less??” Trans folk (as distinct from, say, cross dressers or homosexuals) were much less on the public’s radar in the year 1990; it wasn’t until 1994 that Ace Ventura: Pet Detective made over $100,000,000 by relentlessly dehumanizing a trans woman. The average person would maybe have been able to conceive of the idea that one person in their entire small town might be trans, which is a far cry from present-day estimates of “one or two people in each graduating class in a mid-sized high school.”

In 1950, if you could have even gotten away with asking the question, most people in the United States would have said that very, very few people were anything other than heterosexual. Perhaps, thinking of their confirmed bachelor uncle or the lovely old widows sharing the house down the street, they might have whispered something like “half a percent?” if they were sure that the question wasn’t a trap.

But it’s likely that even gay people in the 1950’s wouldn’t have guessed “one in every thirty adults,” which was the rate of self-report in Gallup polls in 2012, or “one in every fourteen adults” (!) which was the rate in 2022. In 1950, if you had told someone that the would likely pass within nodding distance of multiple non-straight people every single time they went to the grocery store, they would have assumed you were either crazy or slandering their hometown.

The conservative party line goes something like “see?? Once we stopped punishing people for bringing it up, it started happening more and more and now it’s everywhere!”

And this is at least somewhat true, with regards to behavior. To how many people with a given inclination express that inclination, through action (especially out in the open where everyone can see, as opposed to furtively, in private).

But there wouldn’t have needed to be so much glaring and shushing, if the proportion of the population with the inclination were vanishingly small. Societies do not typically wage intense and ongoing pressure campaigns to prevent behavior that 0.0001% of people want to engage in. For as long as there have been classrooms with thirty students in them, there have been two or three queer folk in those classrooms—they simply didn’t talk about it.

(Just like we didn’t talk about sexual assault. It’s not new. It’s just newly un-hidden.)

III. The Law of Prevalence

This—

(transness, queerness, sexual assault)

—is social dark matter. If you’re both paying attention and also thinking carefully, you can conclude that it must be out there, and that there’s probably actually quite a lot of it. But you don’t see it. You don’t hear it. You don’t interact with it.

(Unless you are a member of the relevant group, and members of that group in fact talk to each other, in which case you may have a somewhat less inaccurate picture than all of the oblivious outsiders. Many women were not shocked at the information that came out during #MeToo. Shocked that it came out, perhaps, but not shocked by the stories themselves.)

I’d like to present two laws surrounding social dark matter in this piece, and at this point we’re ready for the first one:

The Law of Prevalence: Anything people have a strong incentive to hide will be many times more prevalent than it seems.

Straightforward, hopefully. People hide things they are encouraged to hide; people do not share things they are punished for sharing.

(Twice now, I have been told by a dear, close friend that they had developed and recovered from serious alcoholism, without me ever even knowing that they drank. Both friends formed the problem in private, and solved it in private, all without giving any outward sign.)

However, while almost anyone would nod along with the above, people do not often stick around long enough to do the final step, and apply it.

Here are some examples of things that people are (or were) encouraged to hide, and nonzero punished for sharing or discussing or admitting to (starting with ones we’ve already touched on):

Alcoholism/alcohol abuse

Sexual assault

Homosexuality (less so than two generations ago, but still)

Transness (less so than a generation ago, sort of? It’s depressingly complicated.)

Left-handedness (much less so than five generations ago)

Being autistic (much less so than a generation ago)

Being into BDSM or polyamory (somewhat less so than a generation ago)

Liking the score from the movie “Titanic” as a seventh-grade boy in N.C in 1998.

Wanting to divorce your partner or thinking that your relationship is toxic/bad (commonplace now, was almost unspeakable five generations ago)

Having some small, deniable amount of Japanese heritage (in the United States, during WWII)

Having some small, deniable amount of black or brown heritage (in the United States, among other places, especially a few generations ago)

Having some small, deniable amount of Jewish heritage (in Europe, among other places)

Having some small, deniable amount of Dalit heritage (in India, among other places)

Not feeling overwhelmingly positive feelings about your infant or toddler, or feeling active antipathy toward your infant or toddler, or frequently visualizing murdering your infant or toddler

Agnosticism or atheism (in religious communities)

Faith or “woo” (in atheistic communities)

Drug use (especially hard drugs)

Being a furry

Cross dressing/drag

Providing or availing oneself of sex work

Psychopathy or borderline personality disorder

Hearing voices or having hallucinations

Being on the verge of breakdown or suicide

Having violent thoughts or urges

Having once beaten a partner, or a child, or a dog

Masturbating to fantasies of rape or torture

Having HIV

Being sexually interested in children, or family members, or animals

Actually having sex with children, or family members, or animals

Having abortions (in red enclaves) or thinking abortion should be banned (in blue ones)

Having committed felonies

… this is not an exhaustive list by any means. But it’s worth pausing for a moment, for each of these, and actually applying the Law of Prevalence to each, and realizing that there’s really quite a lot more of that going on than you think.

No, really.

Seriously.

Your perceptions of how rare something like incest is are systematically skewed by the fact that virtually everyone engaging in it is also engaging in a fairly effortful (and largely successful) campaign to prevent you from ever finding out about it. Ditto everyone who habitually uses opium, or draws tentacle hentai to decompress after work, or thinks Jar-Jar Binks was what made The Phantom Menace a truly great movie.

The punishment our culture levied on left-handed people was fairly tame, relative to (say) the punishment our culture levies on pedophiles (even those who have never abused anyone). Yet even that punishment was enough to hide/suppress seventy-five percent of left-handedness! Three in four left-handers or would-be left-handers were deterred, in the year 1900; incidence went up from 3% to 12% once the beatings began to slow[1].

It’s not crazy to hazard that some of the more-strongly-stigmatized things on the list above have incidence that’s 10x or even 100x what is readily apparent, just like the number of trans folk in the population is wildly greater than the median American would have guessed in the year 1980.

IV. Interlude i: Nazis

There’s something of a corollary to the Law of Prevalence: when the stigma surrounding a given taboo is removed (or even just meaningfully decreased), this is almost always followed by a massive uptick in apparent prevalence.

A very straightforward example of this is Nazi and white supremacist sentiment in the United States, Canada, and Europe over the previous decade. The internet is littered with commentary from people saying things like “but where did all these Nazis even come from?”

In point of fact, most of them were already there. There has not been a 2x or 5x or 10x increase in actual total white supremacist sentiment—

(though there probably has been some modest marginal increase, as more people openly discuss the claims and tenets of white supremacy and some people become convinced of those ideas for the first time, or as the culture war has polarized people to greater and greater forgiveness of those on their side, etc.)

—instead, what happened is that there has been a sudden rise in visibility. Prior to 2015, there was a fragile ban on discussing the possible superiority or inferiority of various races, similar to the ban on discussion of sexual assault pre-#MeToo. In most venues, it simply Wasn’t The Sort Of Thing One Would Mention.

And many, many people, not getting the Law of Prevalence all the way down in their bones, mistook the resulting silence for an actual absence of white supremacist sentiment. Because they never heard people openly proselytizing Nazi ideology, they assumed that practically no one sympathized with Nazi ideology.

And then one Donald J. Trump smashed into the Overton window like a wrecking ball, and all of a sudden a bunch of sentiment that had been previously shamed into private settings was on display for the whole world to see, and millions of dismayed onlookers were disoriented at the lack of universal condemnation because surely none of us think that any of this is okay??

But in fact, a rather large fraction of people do think this is okay, and have always felt this was okay, and were only holding their tongues for fear of punishment, and only adding their voices to the punishment of others to avoid being punished as a sympathizer. When the threat of punishment diminished, so too did their hesitation.

The key thing to recognize is that this is (mostly) not an uptick in actual prevalence. Changes to the memetic landscape can be quite bad in their own right—the world is somewhat worse, now that white supremacy is less afraid of the light, and discussions of it are happening out in the open where young and impressionable people can be recruited and radicalized, and the marginal racist is marginally bolder and more likely to act on their racism.

But it’s nowhere near as bad as it looks. Judging by visibility alone, it seems like white supremacy has become 10x or 20x more prevalent than it was a decade ago, but if there had actually been a 10-20x increase in the number of white supremacists, the world would look very, very different.

Or, to repurpose the words of Eugene Gendlin[2]: “You can afford to live in the world where there are this many white supremacists and white supremacist sympathizers among your neighbors and colleagues, because (to a first approximation) you were already doing so.”

(Ditto anti-Semites, ditto misogynists, ditto pedophiles, ditto people hearing voices, ditto people committing all those perfect crimes that you’ve always been told don’t exist but if you stop and think for twelve seconds you’ll realize that they totally exist, of course they exist, they’re probably happening all the time, and yet somehow the world keeps spinning and society doesn’t collapse, it is worse than you thought but it’s not as bad as you would naively expect, DON’T PANIC.)

V. Interlude ii: The Fearful Swerve

There is a substance called shellac that is made from the secretions of the female lac bug, formal name Kerria lacca. Out in the wild, shellac looks like this:

This substance has many uses. One such use is making the outer shells of jelly beans shiny and hard and melt-in-your-mouth soluble.

Many people, upon discovering that the jelly beans they have been enjoying all their lives are made with something secreted by a bug—

(I mean, what a viscerally evocative word! Secrete. Squelchy.)

—many people, upon discovering that the jelly beans they have been enjoying all their lives are coated in bug secretions, experience a sudden decrease in their desire to eat them.

This is the fearful swerve.

Here is (roughly) how it works:

The human mind has something like buckets, for various pieces of information, and those buckets have valences, or karma scores.

For many people, “jelly beans” live in a bucket that is Very Good! The bucket has labels like “delicious” and “yes, please!” and “mmmmmmmmmmm” and

“Bug secretions,” on the other hand, live in a bucket that, for many people, is Very Bad[3]. Its labels are things like “blecchh” and “gross” and “definitely do not put this inside your body in any way, shape, or form.”

When buckets collide—when things that people thought were in one bucket turn out to be in another, or when two buckets that people thought were different turn out to be the same bucket—people do not usually react with slow, thoughtful deliberation. They usually do not think to themselves “huh! Turns out that I was wrong about bug secretions being gross or unhygienic! I’ve been eating jelly beans for years and years and it’s always been delicious and rewarding—bug secretions must be good, actually, or at least they can be good!”

Instead, people tend to react with their guts. The bad labels trumps the good ones, the baby goes out with the bathwater, and they reach for a Reese’s instead.

(In the case of shellac specifically, this reaction is often short-lived, and played up for comedic effect; there aren’t that many people who give up on them long-term. But the toy example is still useful for understanding the general pattern.)

This same effect often plays out when humans become suddenly aware of other humans’ social dark matter. In the U.S. of the 1950’s (and, rather depressingly, in many parts of the U.S. of the 2020’s), the discovery that Person A was gay would often violently rearrange Person B’s perception of them, overriding (and often overwriting) all of Person B’s other memories and experiences and conceptions of Person A.

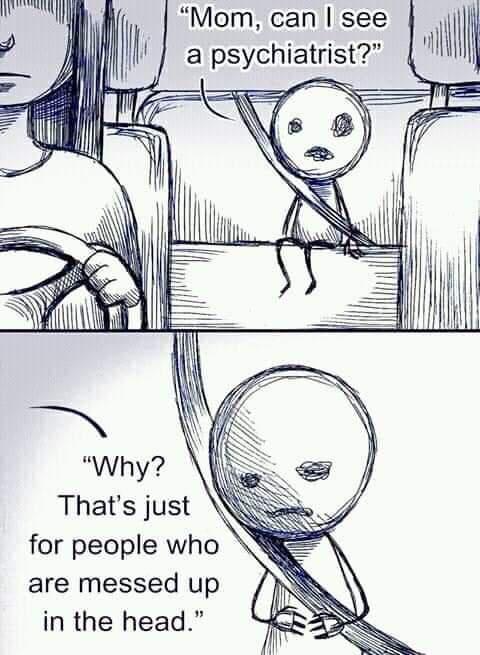

The same thing happens in various parts of the world when people are outed as having been raped, or having had an abortion, or having lost their faith, or having been diagnosed with schizophrenia, or having a habit of taking LSD on weekends, or having a penchant for wearing diapers, or any number of other taboo things. The stereotype of a good and upstanding person is incompatible with the stereotype of [dark matter], and rather than make a complicated and effortful update to a more nuanced stereotype, people often simply snap to “well, I guess they were Secretly Horrible All Along, all of my direct evidence to the contrary notwithstanding.”

This is unfortunately complicated by the fact that this update is sometimes actually correct, as many people discovered during #MeToo. There are, in fact, dealbreakers, and there are people who present a kind and friendly front while concealing horrific behavior, and one negative revelation can in fact be more important than everything else you knew about a person[4]. Such occurrences are (sadly) not even particularly rare.

But! There’s a pretty damn important distinction between thoughts or inclinations, on the one hand, and actions on the other. Most of the horror that suburban parents in the 1950’s would have felt upon discovering that their child’s high school English teacher was gay would have been wrong—wrong in the sense of being incorrect, unfounded, unjustified, confused. The mere fact of being gay (whilst being otherwise well-behaved and in compliance with all social norms and standards, such that most people never even noticed) is not a major risk factor for child molestation, and is not evidence that Mr. So-and-So was actually a ticking time bomb all along and we simply never knew, thank God we got rid of him before he fiddled with somebody all of a sudden after never doing anything of the sort for thirty years.

The fearful swerve is a reflex. It’s one thing to conclude, after conscious thought and careful evaluation, that the things you’ve learned about a person mean that they are irretrievably Bad (especially if what you’ve learned is that they have actually taken harmful action out in the world[5]).

It’s another thing altogether to leap to that conclusion unthinkingly, based on nothing more than stereotypes and pattern-matching. Deciding that “welp, jelly beans are off limits now, because I’m an ethical vegan and shellac is an animal by-product” is very, very different from just going “eww, gross!” and letting that impulse have final say.

VI. The Law of Extremity

When the categorical bucket “autism” was invented, it was built around people who were what we would now call profoundly or severely autistic[6]. Many of them were nonverbal. Many of them had extreme tics. They were incapable of navigating ordinary human contexts, and required highly specialized and intensive assistance to survive even at home or in institutions.

Over time, the medical establishment began to pick up on autistic-spectrum traits in people whose support needs were not quite so great. In 1988, the movie Rain Man introduced the word “autistic” to the broader English-speaking public, and for a couple of decades Dustin Hoffman’s character Raymond was the go-to archetype of a person with autism. Yes, he was disabled, but he could talk, he could walk, he could feed himself, and not every surprising stimulus triggered a meltdown.

In 2010, as a middle school teacher, I encountered my own first bona fide, formally diagnosed autist, in the form of a student named Ethan. Ethan was fully capable of holding up his end of a completely normal conversation (though he much preferred that conversation be about Spore or Minecraft, and was not shy about saying so).

On December 19th, 2021, I ended a months-long process of discovering that I am autistic. These days, somewhere between 10% and 25% of my social circle wears that label as part of their identity.

The Law of Prevalence states that anything people have a strong incentive to hide will be many times more prevalent than it seems.

Part of what makes this possible at all is the Law of Extremity:

The Law of Extremity: if part of the incentive to hide something is that the cultural narrative treats it as damning, dangerous, or debilitating, the median and modal instances of that thing will be many times less extreme than that narrative would have you believe.

The prevalence of autism in 1988 was basically the same as it is today, i.e. really quite startlingly common, overall less rare than red hair. Yes, there are some reasonable hypotheses that certain environmental changes (not vaccines) are leading to an actual ground-level increase in the rate of autism, but if so, we’re talking about something like a 1.5x-3x increase, not a 10x or 20x or 50x increase.

But this claim—that something close to three percent of the population is autistic—would sound absolutely crazy to your everyday moviegoer leaving the theater in 1988 after watching Rain Man. It would sound crazy because that moviegoer’s picture of autism was rooted in an unusually extreme example of what an autistic person looks like. They would think you were claiming that one in thirty-three adults was Raymond Babbit, which is patently false.

The 1988 counterparts of [me] and [my autistic friends] and [my student Ethan] weren’t quite trying to hide their autism in the way that people actively try to hide things like psychopathy and pedophilia (though they probably were spending a ton of personal resources in an attempt to seem more normal than they were on the inside).

But our 1988 counterparts were able to fly under the radar at all because everyone else’s autism-detectors were calibrated on much more extreme and pathological variants of the traits that they themselves carried.

When I wrote a public Facebook post letting my social circle know that I am autistic, a friend of mine replied with the following (abridged):

I’ve been uncomfortable with this label myself because this one time I went to a grocery store (to buy a bottle of a specific dish soap to make giant soap bubbles) and there was this guy meticulously re-stacking the product who I just ignored because I thought he was a store employee but then he grunted and shoved my hand away when I tried to take one. An older fellow identifying himself as the man’s care taker showed up and had to explain the situation. Then I had to drive to another store to get that specific dish soap.

But, anyway, my point is, neither of us are like that guy, and that’s the sort of case I thought the psychiatric label was designed for.

To which my partner @LoganStrohl replied:

because the characteristics you’re mostly likely to observe in someone are the easy-to-see-from-the-outside ones (unusual social behaviors, motor problems, speaking problems), you’ll probably by default see people with extreme versions of these more visible characteristics as “more autistic”.

but there are autistic people who can neither walk nor talk but are unusually good *for a median human* at flirting. there are autistic people who have severe world-shattering meltdowns daily from sensory overload yet have built such convincing masking and coping mechanisms that their bosses do not know they’re anything besides “a bit quirky”. there are autistic people who react so violently and explosively to perceived rule violations that they need constant supervision to protect others and themselves, yet they find life in the middle New York City comfortable and exciting rather than overwhelming.

i think there is a thing going on with intelligence, where people with higher intelligence tend to succeed more at going about normal life than people with lower intelligence. if two people share basically the same innate tendencies wrt information processing style, social processing architecture, sensory processing ability, etc.; but one is IQ 95 while the other is IQ 160; then the IQ 95 person may seem like a total disaster who can’t dress himself let alone hold down a job, while the IQ 160 person has stable employment, a mortgage, and lots of friends who appreciate his quirky interests and moral passion. one of these people isn’t more autistic than the other; they’re just more *disabled* than the other.

there’s a very similar effect from support. imagine two very similar autistic people again. one of them is born into a wealthy progressive family, they go to the same school and live in the same town the whole time they’re growing up, their parents organize a lot of structured interest-based socialization for them, and then they go to college where food is provided by resident services in the cafeteria while they study computer science until they move on to the Google campus. the other person grows up moving from foster home to foster home in a conservative area where differences are seen as threatening, and they’re considered a problem child and put through ABA therapy that punishes their coping strategies and tries to cure their disorder. the first person will not stick out nearly as much to someone looking for obvious external signs of autism.

given that Duncan is both very intelligent and has been very well supported in the relevant ways throughout his life, then on the hypothesis that he is autistic, we should expect his internal experiences and personal struggles to be WAY more similar to those of supermarket guy than they appear (much more similar to those of supermarket guy than to those of a randomly chosen person)

…which is in fact true; I was immediately able to recognize and describe several ways in which the supermarket guy seemed to be something like a less-well-contained version of myself.

The first autistic people to rise to the level of attention were those who:

Had such intense versions of the traits that they outshone everything else

Lacked the support structures and coping strategies that allow people with the traits to overcome them and appear to not-have-them.

And thus, when the stereotype (/archetype) of autism began to crystallize, it crystallized with those people at the center, when in fact they were well to the right side of the bell curve.

This (claims the Law of Extremity) is approximately always going to be true. It doesn’t matter if you’re talking about autism or homosexuality or sexual assault or drug use—when it comes to social dark matter, what you hear about on the news and see depicted in movies and shows will always be an unusually vivid version of [whatever it is]. Someone who couldn’t hold it together, couldn’t keep up the facade—someone whose [thing] is so intense, or whose self-control is so tattered, that they can’t keep it under wraps like everybody else[7].

A term-of-art in this domain is representativeness; there’s a difference between the most memorable/most recognizable version of a thing, and the actual most common or typical example. The classic archetype of a basketball player is a thin, muscular, dark-skinned man, pushing seven feet tall and wearing a jersey with a number on it. But the vast majority of the people actually playing basketball at any given moment do not fit this description[8].

You could call it the Law of Caricature, perhaps. The picture of a drug user is a lank, twitchy, pale young man with greasy hair and disheveled clothes and wild, suspicious eyes—but most drug users look nothing like that. A New Yorker cartoon depicting a Jew might have characteristic long braids and dark clothes and a yarmulke and a prayer shawl with a star of David—but most Jews do not look like that, most of the time.

(If #MeToo taught us anything, it taught us that you can’t identify rapists and molesters simply by looking for people who “look like” rapists and molesters.)

Just as 95+% of people who play basketball look nothing like LeBron James, so too is it obvious (if you pause and actually take the time to add 17 to 26) that 95+% of psychopaths aren’t serial killers and 95+% of pedophiles aren’t child molesters and 95+% of drug users have never mugged a stranger on the street to pay for their next hit.

(“Even if most Dark Wizards are from Slytherin, very few Slytherins are Dark Wizards. There aren’t all that many Dark Wizards, so not all Slytherins can be one.”)

The perception that all of these traits are necessarily extreme and dangerous is explained by the fact that the visible examples of [psychopaths] and [pedophiles] and [drug users] are all drawn from the extreme end of the distribution. When the penalty for a certain kind of dark matter is steep enough, the only individuals you notice are the ones who cannot escape notice, and if you don’t keep your brain on a fairly short leash, it will naturally default to a corresponding belief that the entire population of [psychopaths] and [pedophiles] and [drug users] centers on those individuals.

But in all likelihood, for every person wandering the street raving about freemasons, there are literally dozens who hear voices from time to time and never unravel enough that they even get diagnosed.

(Or, to put it another way: you can’t confidently deduce an absence of people-hearing-voices in a given population from an absence of people raving on the street, just like you shouldn’t be confident that no one is playing basketball because none of them are seven feet tall.)

(Similarly, #MeToo showed us that it’s a mistake to conclude that none of the people in our lives have been sexually assaulted simply because none of them are suffering nightmares and panic attacks and having trouble holding down a job and conspicuously avoiding being in the same room as their boss. Most rape victims don’t look anything like the training data our society handed us.)

VII. Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Sabien

I once got into a protracted disagreement with a colleague about the prevalence of a specific form of social dark matter. I used eight different independent lines of reasoning to try to reach an estimate of how commonplace it might be, each of which gave me back an answer somewhere in the ballpark of 0.5% − 5%.

(Several of the lines of reasoning were very crude/coarse/rudimentary, such that if any one of them had been my sole source of intuition I would have been embarrassed to proffer my guess, and might have preferred to say “I really don’t know.” But eight unrelated crappy methods all giving answers in the same order of magnitude felt like real reason for confidence.)

My colleague did not buy it[9]. They were insistent that prevalence had to be well below one in a thousand. They were someone in whom people frequently confided, on a fairly wide range of issues—”I’ve been told equally damning things, multiple times; I find it hard to believe I would have simply never heard this particular one, from anyone, unless it is in fact vanishingly rare.”

And yet I had received (and continued to receive) confidences from multiple such people—more than one of whom was also close to my colleague and yet chose not to extend their trust in that direction.

This is no accident; most people systematically drive away such confidences (and I work rather hard, and rather deliberately, to earn them). The driving-away is usually not intentional; it’s a vibe thing. It comes across in offhand comments and microexpressions and reflexive, cached responses that the speaker will hardly even notice themselves saying (because they’re so self-evidently true).

If you walk around aggressively signaling the equivalent of “What!?? There ain’t no faggots in this town,” then it should be no surprise to you that your lived experience is that none of the people around you are gay (even though base rates imply that quite a few of them are).

If you exude “we are all brothers and sisters in Christ,” then you will generally not hear from atheists (except the unusually militant and confrontational ones), and you will likely underestimate their prevalence in your religious community.

(And you may also underestimate the prevalence of nonbinary folk in your immediate vicinity! The thing that tells someone’s gut that you are not safe to confide in is often indirect or subtle, and speaking always of “brothers” and “sisters” and never of “siblings” or “children” is exactly the sort of subtle signal that puts the animal instincts inside of a marginalized person on high alert.)

I have personally been in rooms where someone was trying to make a small accommodation for [some trait X], or push for being less alienating and offputting to [Xers], and heard colleagues push back, not merely against the proposed changes, but against even discussing them, arguing “look, this is all hypothetical, it’s not like any of us here are actually [X], why are we even spending time on this?” when I knew for a fact that at least one other person in the room was secretly [X].

Dwight: Okay, now who wrote this hysterical one? ‘Anal fissures’?

Kevin: That’s a real thing.

Dwight: Yeah, but no one here has it.

Kevin: (softly) …someone has it.

If you loudly assert that of course none of the people in your circle are suppressing deeply violent fantasies, all of your associates are good people—then the good people around you who have their deeply violent fantasies well in hand are unlikely to disabuse you. If you would never hear from a pedophile in the world where there are none around you, and you would also never hear from a pedophile in the world where there were secretly a dozen in your social circle, then you can’t use the fact of having never heard from one to tell you which world you’re in.

It’s a bit dangerous, epistemically, to claim that a lack of observations of a thing constitutes evidence for that thing, but in the case of social dark matter, it really can be. There’s a spectrum ranging from “I will actively harm white ravens if I see them” to “I will actively reward white ravens if I see them,” and where a would-be observer sits on that spectrum strongly influences how many white ravens will allow themselves to be noticed in the first place.

“I won’t actively harm white ravens, necessarily, but I react to claims of their prevalence with open incredulity and scoff at people who claim to see them regularly and outright ignore arguments that we should expect a lot of them on priors and also by the way I sometimes talk about how white ravens are kinda bad maybe, and make faces whenever they’re brought up” is a lot closer to the former than the latter. You don’t want to fall into conspiracy-theory type thinking, but you don’t have to observe all that many white ravens surreptitiously blacking their feathers with coal dust before you learn to roll your eyes at the people running around insisting that 99.9% of all ravens are definitely black (“and thank goodness for that!”).

(After all, what does one have to gain by saying something incendiary like “I was introduced to sex by an adult, as a child, and I think that this was straightforwardly good for me, actually”? The few times I have seen an otherwise-apparently-happy-and-well-adjusted adult make a credible claim along those lines, they were subsequently screamed at, excoriated, gaslit, condescended-to, told that they were a victim, told that they were stupid, told that they were sick, told that they were evil, told that they were enabling child molesters, interrogated and pressured to give up the name of whoever-it-was, kicked out of various social and professional circles, and generally treated as liars or mocked for how they are obviously in denial about their own suffering and brokenness (their stable, fulfilling adult lives and livelihoods and relationships apparently notwithstanding). And given that this is the obvious, predictable-in-advance outcome of any such disclosure, most people who might be in a position to say such a thing simply don’t bother. To the extent that these people are out there, they have no incentive whatsoever to disillusion the rest of us. Which is bad news for those of us who want to understand the actual state of affairs!)

You also don’t have to observe all that many furtive white ravens to develop a strong default mistrust of the things that people confidently claim to know about the properties of white ravens (since all of their conclusions are drawn from an extreme, impoverished, and wildly non-representative data set). It’s like trying to learn about the effects of various drugs by studying only individuals in court-ordered rehab. The people who are most emphatic about knowing precisely how awful X is tend to be the very same ones who plug their ears and go lalalalala whenever anyone pops up with counterevidence.

(Which, again, isn’t to say that X is secretly good, necessarily. Just that the current situation doesn’t let you tell one way or the other. If nobody ever talked about sex at all, and so you based your entire understanding of human sexuality on the study of convicted rapists, you would likely have some pretty weird beliefs about sex-writ-large, even if all of your individual bits of evidence were true and accurate.)

VIII. The Law of Maybe Calm The Fuck Down

Okay, that one’s not actually a law. But it’s the right prescription, in the sense of being the correct action to take a majority of the time.

Core claim: If you were a median American in the United States in the year 1950, and you discovered that your child’s teacher or coach or mentor was secretly in a homosexual relationship with another adult, you would very likely have felt something like panic. The median American in that era would have concluded that the teacher was obviously a clear and present danger, and taken immediate steps to protect their child from that danger, and the resulting fallout would have likely completely derailed that person’s life.

And this (I further claim) would almost certainly have been bad—a moral tragedy, a miscarriage of justice—and at the root of the badness would have been people being really really wrong, as a question of simple fact, about what was implied and entailed by the mere presence of [homosexuality[10]].

Ditto if someone adopted the Socially Appropriate Level of Panic about, say, a female neighbor in the 1600s after spotting her stewing herbs in the moonlight.

Ditto if someone adopted the S.A.L.o.P about their neighbor in California in 1942, after discovering that they were not, as had been assumed, one-eighth Korean, but actually one-eighth Japanese.

Since our moral evolution has probably not yet brought us to a state of overall perfect judgment, it seems quite likely to me that there are dozens of other tragedies of similar form taking place right now, in today’s society—conclusions being drawn, and consequences being meted out, which are overwhelmingly approved-of but which future generations will (correctly) assess as having been wildly unjustified and excessive and wrong.

(That’s the main thing I’d like to see happen less. I’m not exactly impressed with how the machine handles actual rapists and racists and serial killers and child molesters, either, but I feel much less urgent about improving the situation for those people; even in situations where their actions weren’t exactly choices and they’re unfortunately subject to forces beyond their control, the majority of my sympathy and protective energy nevertheless goes to their victims and their potential future victims.)

The casus belli of this essay is “can we maybe not, then?” and this final section is about how.

Much of the subsequent advice will be incomplete, and useful only if laid atop some preexisting base of skill and motivation. I’m going to try to gesture at the shape of the problem, and in the general vicinity of (what I suspect are) the solutions, but the actual nitty-gritty is up to you, and will require nonzero mental dexterity and field-ready metacognitive competence. I’ll be recommending a class of actions that are only available to you if you are at all capable of e.g. noticing a thought while it’s still forming, or recognizing the difference between an observation and an interpretation of that observation, or pausing and counting to ten and having the fact that you paused and counted to ten actually break a runaway cascade of thoughts.

I’ve sketched out The Bad Thing above in brief, but to add a little more detail, here’s the problem as I understand it:

Your brain receives evidence that Person A has Trait X, which is social dark matter and is widely believed to be virulently awful.

This triggers a preexisting mental scheme that your society has helpfully gifted you, causing your brain to interpret its observation that [Person A has Trait X] as meaning that [Person A has done, in the past, or inevitably will do, in the future, whatever awful thing[11] is characteristic of Trait-X-ers]. In most cases, your brain does this without noticing that it is making any intuitive leaps at all[12], just as you aren’t usually consciously aware of the step between [observing certain specific patterns of shimmering light] and [recognizing that what you are observing is an instance of the class “fish”].

Your brain, thus believing itself to be in the presence of a Clear And Tangible Threat, offers you up some form of Panic, so as to fill you with motive energy to Do What Must Be Done, which in most cases includes...

...some form of “outing” the person as a Trait-X-er, whether via internet megaphone or whisper network or a call to the police or the rousing of an angry mob.

(This part does not usually feel like outing someone—from the inside, it feels more like Doing Your Due Diligence, or Warning The Potential Victims, or Making Sure Everyone Is Aware, or perhaps Letting Everyone Know They’ve Been Lied To, For Years. In other words, there’s usually some amount of righteousness or sense-of-responsibility, a feeling of engaging in a public good or protecting the vulnerable or fulfilling your civic duty.)As the meme spreads, each person who comes into contact with it does their very own fearful swerve, and Person A’s life is ultimately made substantially worse (they are fired, institutionalized, jailed, evicted, shunned, blacklisted, etc).

It seems to me that there are two basic strategies for replacing this story with a more moral, less wrong one. One of them is sort of clunky and brute-force-y, but it has the virtue of being a thing you can do once, in the course of a single afternoon, and then be done with. The other is more integrated, and has some ongoing attentional costs, but the particular kind of attention required happens to be useful for a bunch of other things and so might be worthwhile anyway.

The brute force strategy is to do something like write down and consciously consider some ten or twenty or thirty important flavors of dark matter, and to meditate on each for five minutes and figure out your personal policy around each of them. For example:

What do I actually believe about the base rate of suppressed rage in the general population, and why do I believe it? How suppressible, in a fundamental sense, do I think rage is, and why? What would I see if I were wrong? What things do my current beliefs rule out, and are any of those things happening?

What behaviors on the part of someone with suppressed rage are dealbreakers, assuming that the mere existence of (successfully) suppressed rage is not?

What other traits are comorbid with suppressed rage turning out to be A Problem, Actually? On the flip side, what other traits, found alongside suppressed rage, would be substantially reassuring?

What events could I observe, along the lines of “if their suppressed rage were something I should actually be concerned about, I would have seen them doing X, Y, or Z; if I haven’t ever observed X, Y, or Z, then it’s probably fine”? (See also: Split and Commit)

In what specific circumstances that are unlike all my previous experiences of them would I expect my preexisting models to fail? What are the boundaries of my “training distribution,” and what lies outside of them? For instance, have I already seen them drunk, and if so, did they seem meaningfully scarier or less stable, or was it actually just fine?

In short: to what extent, and for what reason, do you endorse actually distrusting people who (it turns out) are carrying around vast quantities of hidden rage, or drug users whose drug use is invisible to outside observers, or perverts whose perversion has remained confined to their fantasies for decades, or people with an utter absence of empathy whose outward behavior has nevertheless passed everyone’s emotional Turing tests?

(By the way, the point here is not to presuppose the answer—perhaps you do still endorse distrusting them! Different people have different thresholds for risk, after all, and different people assign different moral weights to various harmful behaviors. The thing I am advocating against is joining lynch mobs by reflex and then absolving yourself of responsibility because you were merely following the orders of your culture. It’s every moral person’s job to do better than what was handed to them, even if only by a little, and actually bothering to try to answer this question at all is a damn good start.)

One hugely beneficial side-effect of thinking through specific kinds of dark matter that are likely pretty prevalent in the population is that it gets the initial shock out of the way. When you believe yourself to live in a world where no one around you regularly visualizes murdering their coworkers in grim detail, it is understandably unnerving to suddenly discover that someone on your team does!

And in the resulting shock, confusion, and panic, it’s easy to succumb to a generic, undirected pressure-to-act. It feels like an emergency. It feels like you’re in danger. It feels like something must be done.

(And it’s easy to forget the Law of Prevalence, and that probably several of your coworkers have such thoughts, and it’s easy to forget the Law of Extremity, and that such thoughts probably influence and control people’s actual behavior much less than media has primed you to think.)

And people who are frightened and disoriented and triggered often flail, taking actions that are desperate and disproportionate and poorly thought-out as they try to claw back some sense of safety and control[13].

Running through considerations like the above for even just a handful of specific strains of social dark matter does something like inoculate you against that sort of panic response, such that when you drop by your friend’s house unexpectedly and discover them halfway into putting on a fursuit, you aren’t wholly ad-libbing, and have some previous prep work to fall back on.

(It’s sort of like how, at least in theory, having practiced kicks and punches in the context of martial arts kata means that your muscles have pretrained patterns that will fire if you end up in an actual fight. Meditating on how you would ideally want to respond to a given unmasking makes it more likely that you will respond that way, as opposed to doing something more frantic and mercurial.)

The other path to not-doing-the-thing is to catch it in the moment, i.e. to notice that your brain is going off the rails and intervene before it does anything drastic and irrevocable.

(Often, literally just noticing what’s happening at all, as in, popping out of the object-level flow and thinking/saying something like “I notice I’m panicking” is enough.)

The whole problem with social dark matter is that our underlying base of experience is deeply impoverished, which means that our unexamined beliefs are largely wrong, which means that our default responses tend to be miscalibrated and broken. It’s like someone who’s never driven on ice before reflexively slamming on the brakes, because slamming on the brakes usually makes a car stop—your mental autopilot isn’t prepared for this, and so letting your default reactions guide you is a recipe for disaster.

But if you can successfully replace even one would-be link in the chain with the action [noticing what’s actually happening in your brain], the odds of snapping out of it and waking up go through the roof.

(For a dozen more essays on this, check out The Nuts and Bolts of Naturalism.)

So here, for your perusal, is a(n incomplete) list of things you might notice, if you are in the middle of something like a fearful swerve—thoughts or feelings or sensations that could be a clue that you want to do something like slow down and start reasoning more explicitly.

As mentioned above, a sense of righteousness or steely resolve or moral obligation. You might feel like you have no choice, like you are compelled to respond in a certain way, like the situation demands it.

As mentioned above, a sense of urgency—that the threat is imminent, and something must be done immediately.

A sense of shock and horror—that what you just learned is huge, and vast, and important, and very, very surprising. The opposite of mundane. Significant, in a dire sort of way.

Confusion, disorientation, disbelief—something about this is incoherent, surely not, it can’t be true, this is so discordant with everything else I know about them.

A feeling of reshuffling, or throwing-away—that you’re having to suddenly reassess and reevaluate everything you thought you knew about a person, that every memory is suspect, that maybe it was all a facade, that maybe you can’t trust any of your previous, cached beliefs.

A feeling of certainty or inevitability—that you just know what this revelation means, that its consequences are obvious. You can see the pattern, you know how the dominos will fall (or have already fallen). That A necessarily and absolutely implies B, or even that A simply is B. That what you’ve learned means something else, something more, something awful.

That this is a situation you’ve never actually encountered before and have no direct experience with, and yet (curiously) you feel like you … kinda know a lot, actually? …about what you’re supposed to do next, and how to respond. That there’s a clear script, a prescribed set of Ways You’re Supposed To React—that you know just what you’re supposed to say as soon as you can find a teacher to tell.

A sense that others will back you in your outrage or dismay; that you’re feeling strong feelings that are perfectly normal and what anyone would feel; that you have clear social consensus on your side.

All of these things tend to push people forward along the default track. They’re the opposite of the standard, virtuous, building-block move of rationality: “wait, hang on a second. What do I think I know, and why do I think I know it?”

And if you manage to become cognizant of any of those things happening in your brain, then you’ve already created space for yourself to simply not take the next step. To break the cascade, and instead take any number of options that buy you thirty seconds of additional breathing room.

(Counting slowly to ten, taking a dozen deep breaths, saying out loud “pause—I need to think,” getting up and going to the bathroom, remembering your feet.)

The point is not so much to do some specific wiser move as it is to simply avoid doing the known bad thing, of blindly following your broken preconceptions to their obvious and tragic conclusion.

(Remember: if, after thirty seconds of conscious awareness and deliberate thought, you come to the conclusion “no, this actually is bad, I should be on the warpath,” you can always ramp right back up again! Any panic that can be destroyed by a mere thirty seconds of slow, deep breathing is probably panic you didn’t want in the first place, and it’s pretty rare that literally immediate action is genuinely called-for, such that you can’t afford to take the thirty seconds.)

IX. Recap and Conclusion

What is social dark matter?

It’s anything that people are strongly incentivized to hide from each other, and which therefore appears to be rare. And given that our society disapproves-of and disincentivizes a wide variety of things, there is a lot of it out there.

By the Law of Prevalence, any given type of social dark matter is going to be much more common than your evidence would suggest, and by the Law of Extremity, instances of that dark matter are going to tend to be much less extreme than you would naively guess.

If you lose track of these facts, you can go crazy. You can end up thinking absolutely insane things like “all psychopaths are violent, manipulative bastards” or “pedophilia is an absolute, irresistible compulsion” or “none of the women I know have ever been sexually assaulted[14].”

You can end up thinking these things because your mind takes, as its central, archetypal examples of a thing, what are actually the most extreme, most visible, most unable-to-be-hidden instances of it.

As a result, when you glimpse something through a window or someone offers you a confidence or you stumble across an open journal page, you are in danger of making some pretty serious mistakes, chief among them concluding that this real person is well-modeled by your preexisting stereotype.

(This is called “bigotry”—reducing someone to a single demographic trait and then judging them based on your beliefs about that trait.)

And as a result of that, there are frighteningly high odds that you will fly off the handle in some fashion, and punish them for things they not only haven’t done, but also very well might never have done in the future, either.

And that’s kind of a bummer, and maybe something that you don’t want to do, on reflection! Fortunately, you have other options, such as “think through such situations in advance” and “develop the general ability to notice your brain going off the rails, and when you do, maybe just … slow down for a bit?”

I will reiterate that I think we have different moral responsibilities toward people with dark matter traits, versus toward people with dark matter actions. The advice “think it through in advance” and “slow down for a bit in the moment” applies equally well to discovering that your partner fantasizes about violently raping people as it does to discovering that your partner has violently raped someone, but in the latter case, the correct thing to do is (pretty often, at least) to out and report them. The reason you don’t necessarily out the person in the former case is because our society is systematically confused about how rare and how damning the existence of a rape fetish really is—

(largely by virtue of making it extraordinarily difficult to go gather the data, although some heroes are trying anyway)

—and so you’re causing many of their future interactions with employers and friends and potential romantic prospects to be unfairly dominated by this thing that may actually have very little to do with their core character and their actual behavior.

And that’s bad! It’s bad to punish the innocent, and when it happens, it just further reinforces the problem, making other innocents with the same traits hide even harder in a spiral of silence.

If you would like to think of yourself as the sort of person who would hide Jews from the Nazis, because the things that the Nazis believed about Jews being fundamentally and irretrievably toxic and horrible and corrosive and evil were simply wrong—

If you would like to think of yourself as the sort of person who wouldn’t have destroyed the career of a high-school English teacher in the 1950′s, because the things that society believed about gay men being universally corrupting sex-craved child molesters were simply wrong—

If you would like to think of yourself as the sort of person who wouldn’t have burned witches, or ostracized prostitutes, or stigmatized the mentally ill, or fought to maintain segregation, then you should apply the same kind of higher perspective now, and see if you can sniff out the places where the current social consensus is malignantly confused, just as the Jew-hiders and slave-rescuers and queer allies of the past saw past their societies’ unquestioned beliefs[15].

My parting advice, in that endeavor: take seriously the probability that you have not, in fact, internalized this lesson. This essay, by itself, was probably not enough to get you to really truly grok just how many sadists and coke users and schizophrenics and brotherfuckers and closeted Randian conservatives and Nickelback fans you have in your very own social circle.

They were always there, and (in many cases) things turned out okay anyway. When you have an unpleasant revelation and it feels like the sky is falling, check and see whether there’s an actual problem that requires you to take action, or whether it’s just your preconceptions shattering[16].

Much of the time, it’s the latter, and acting anyway is what leads to tragedy.

Good luck.

- ^

Part of what gives me confidence to name the Law of Prevalence the Law of Prevalence, rather than the Guess of Prevalence or the Maybe of Prevalence, is that this happens basically every single time a given stigma is reduced.

- ^

“What is true is already so.

Owning up to it doesn’t make it worse.

Not being open about it doesn’t make it go away.

And because it’s true, it is what is there to be interacted with.

Anything untrue isn’t there to be lived.

People can stand what is true,

for they are already enduring it.” - ^

With a special exception for honey, somehow; never underestimate the power of normalization.

- ^

When a single revelation triggers a massive update, it’s usually (in my experience) because one’s model of the other person ruled out that they would ever do X, and so discovering even a single instance of X is a Big Deal because it means that one’s model of X being firmly off limits was fundamentally flawed.

- ^

It’s a reflex people do at themselves, too. Social dark matter is often dark to the person possessing it; people often dread finding out or admitting (even just to themselves) that they are queer or lack empathy or are turned on by violence or were sexually assaulted, etc.

- ^

Or perhaps highly disabled people with autism; sorry, I’m not sure where we currently stand with respect to which terminology manages to be neutral.

- ^

Or someone who chooses not to, for various reasons, but when the incentives are steep, few people make that choice and so you’re still looking at someone who is Notably Nonstandard.

- ^

I recall one of my partners (who worked as a stripper) mentioning that their father remarked “strip clubs are where dreams go to die,” to which my partner’s knee-jerk response was “what? No—strip clubs are where pre-meds go to pay off their student loans.”

- ^

They also, for the record, did not rebut or even substantively engage with any of my eight distinct lines of reasoning. They ignored that part of my argument completely, as if I hadn’t said anything at all.

- ^

There are child molesters out there! Extremely distressingly many! Something like ten percent of all minors are sexually abused, and often by teachers and pastors and scoutmasters and other Trusted Authority Figures! It would be great if we could figure out how to actually preemptively identify such people. But “they’re gay” just … turned out not to be a marker, in the way that people in the 1950′s wanted it to be. And being overconfident in your belief that you’ve found a proxy or correlate, when you haven’t, makes things worse for victims. It makes you wrongly attack trustworthy and innocent people who have the trait, and it makes you wrongly trust dangerous people who lack it.

- ^

Some various examples: they will betray the United States to Japan, or brainwash your children into thinking that they should cut off their own genitals, or steal your spouse’s valuables and sell them to a pawnshop to fuel their addiction, or try to play doctor with an unsuspecting child, or lose control in a traffic jam and grab their gun and kill someone.

- ^

While in the process of writing this very essay, I made a Facebook post in which I went out of my way to be careful with the label “psychopath,” and this triggered the following real-world example of the thing, happening in real time:

I am stuck at the idea that it’s bigoted to tell someone not to date or get close to psychopaths. Like, dude, would it be bigoted to say “don’t marry a woman who will baby trap you, or one who will immediately run away with your baby”? Like, these are obvious no goes in the mating pool, and all parents should tell their kids. “Once upon a time, we were in Egypt. Oh, and also avoid psychopaths. People who take pleasure in hurting others make bad social connections on any level.”

Also, where on the surface of the earth can you be if not engaging with psychopaths is a difficult problem? ‘I would lose so many potential social connections by filtering out (checks notes) enjoys hurting people.’ Jeez, do you work for the police or for a bank? Are your coworkers doing lines of coke in the bathroom or straight up at their office desk?

The person replying to me seems unaware that they are making a leap from “psychopath” to “liar/manipulator/sadist.” They don’t have distinct buckets for separately assessing [A], [B], and [A → B]. The archetype is the whole bell curve, as far as they know. It’s analogous to the (also often completely elided) differences between [pedophiles] and [child molesters], or between [people with violent sexual fantasies] and [rapists].

- ^

This is true when reacting to epiphanies about your own dark matter, too; it’s likely that at least some queer suicides are not just about predictions of how others will treat them, but about a desperate attempt to solve the problem from the inside. Please just breathe.

- ^

With the Different Worlds caveat that bubbles do exist and there probably is somebody out there for whom this statement is actually true. But you can’t be (responsibly) confident in such a belief simply because the women around you never talk about it.

- ^

I will note that one of my beta readers helpfully provided the psychopathic perspective that these empathetic and ethical perspectives are not particularly motivating. I think that’s a solid point! I would bet on the existence of a selfish, purely pragmatic argument for these actions, but I have not actually gone out and located it. A short gesture in the direction of my intuition is “on long enough timelines and with broad enough horizons, the actions taken by an MTG black agent often converge with those taken by an MTG white one.”

(There’s also a purely pragmatic argument for going with the flow and not rocking the boat, though, and I ruefully acknowledge that it may be correct, according to their values, for most of my psychopathic readers to shrug and not help with this one.) - ^

This is not to say that the situation is always good or even fine. As #MeToo demonstrated, often things are very, very bad, and society just … ignores it, and keeps on churning. Often it would be nice if the world were more derailed by ongoing atrocity, but whether the dark matter is “good” or “bad,” either way we can’t get to a place of commensurate, appropriate reaction until we can manage to look straight at reality without distortion and talk clearly and frankly about what’s actually going on.

- How do you feel about LessWrong these days? [Open feedback thread] by (5 Dec 2023 20:54 UTC; 106 points)

- Recent and upcoming media related to EA by (EA Forum; 28 Mar 2024 20:32 UTC; 104 points)

- What should the EA/AI safety community change, in response to Sam Altman’s revealed priorities? by (EA Forum; 8 Mar 2024 12:35 UTC; 30 points)

- Virtue taxation by (12 Jul 2024 14:56 UTC; 9 points)

- 's comment on My Clients, The Liars by (11 Mar 2024 3:46 UTC; 3 points)

The first time I read this I stared at it and went “wait, here’s an obvious counterexample. It’s a thing that basically nobody wants to engage in, but there’s a pretty intense social pressure not to- oh wait.”

I’m interested in how one might ever become justifiably confident a particular piece of dark matter really doesn’t exist or is as rare as you’d suspect it is. I’m fairly confident there aren’t shapeshifting lizardmen hiding among my friends for instance. I want there to be a way to trade action for knowledge- to credibly claim I won’t get upset or tell anyone if a lizardman admits their secret to me- but obviously the lizardman wouldn’t know that I could be trusted to keep to that, and anyway it is sometimes preferable to know without making that commitment.

The thing people are generally trying to avoid, when hiding their socially disapproved of traits, isn’t so much “People are going to see me for what I am”, but that they won’t.

Imagine you and your wife are into BDSM, and it’s a completely healthy and consensual thing—at least, so far as you see. Then imagine your aunt says “You can tell me if you’re one of those BDSM perverts. I won’t tell anybody, nor will I get upset if you’re that degenerate”. You’re still probably not going to be inclined to tell her, because even if she’s telling the truth about what she won’t do, she’s still telling you that she’s already written the bottom line that BDSM folks are “degenerate perverts”. She’s still going to see you differently, and she’s still shown that her stance gives her no room for understanding what you do or why, so her input—hostile or not—cannot be of use.

In contrast, imagine your other aunt tells you about how her friends relationship benefitted a lot from BDSM dynamics which match your own quite well, and then mentions that they stopped doing it because of a more subtle issue that was causing problems they hadn’t recognized. Imagine your aunt goes on to say “This is why I’ve always been opposed to BDSM. It can be so much fun, and healthy and massively beneficial in the short term, but the longer term hidden risks just aren’t worth it”. That aunt sounds worth talking to, even if she might give pushback that the other aunt promised not to. It would be empathetic pushback, coming from a place of actually understanding what you do and why you do it. Instead of feeling written off and misunderstood, you feel seen and heard—warts and all. And that kind of “I got your back, and I care who you are even if you’re not perfect” response is the kind of response you want to get from someone you open up to.

So for lizardmen, you’d probably want to start by understanding why they wouldn’t be so inclined to show their true faces to most people. You’d want to be someone who can say “Oh yeah, I get that. If I were you I’d be doing the same thing” for whatever you think their motivation might be, even if you are going to push back on their plans to exterminate humanity or whatever. And you might want to consider whether “lizardmen” really captures what’s going on or if it’s functioning in the way “pervert” does for your hypothetical aunt.

I don’t have an answer for your question about how you might become confident that something really doesn’t exist (other than a generic ‘reason well about social behaviour in general, taking all possible failure modes into account’). However, I would point out that the example you give is about your group of friends in particular, which is a very different case from society at large. Shapeshifting lizardmen are almost certainly not evenly distributed across friendship groups such that every group of a certain size has one, but rather clumped together as we would expect due to homophily.

Edit: I see this point was already addressed in Bezzi’s response on filter bubbles.

So, to put it shortly, there are more of them, but most of them are not what you think.

This feels a bit confusing. I mean, if they are not what I think they are, could it mean that we are kinda talking about two different things? There are many “people on autistic spectrum”. There are few “rain men”. It’s not that the former statement is more true than the latter; they are statements about different things. Are we actually debating the territory here, or just disagreeing about what the label “autist” should refer to?

(Is the conclusion I am supposed to take here something like: Many people are pedophiles, but most pedophiles actually don’t want to have sex with kids… they just think that kids are kinda cute? Many people are psychopaths, but most psychopaths do not lack empathy… they just disagree with some effective altruist ideas?)

In case of autism, the statement about territory is that sometimes the things you assumed to be binary or at least bimodal are actually on a continuum ranging from normal to the extreme. And therefore… you should not have a word for “people at the extreme end of this continuum”? Words exist for a reason; apparently someone finds it useful to talk about the extreme end. Perhaps we should just be very careful to avoid a fallacy of assuming “because we have a special word for it, it must be binary or bimodal”. (And yet somehow, we can talk about “tall people” without assuming that height is bimodal. Perhaps because height is not a sensitive topic?)

But this is probably not what you wanted to say. The lesson about homosexuals was supposed to be “there are more homosexuals than you (an openly homophobic person, or a person living in a homophobic society) assume”, not just “sexual orientation is a continuum”; even if the latter is also true. Similarly, the lesson about sexual assault is not just “sexual assaults happen on a continuum… from rape at one extreme, to just saying hello or smiling at someone who doesn’t want to be smiled at”. The lesson is that there are actually more sexual assaults (in the usual meaning of the word) than we assumed (but coming from people who often do not match our expectations, leaving victims who often do not match out expectations).

...in other words, I think you are talking about an important and true topic, but when I try to put it in exact words, I find the concept slippery. Could it perhaps be two or three different things? (“a typical X is not what you imagine” vs “there are more X than you imagine, even using your current idea of X”) Or both at the same time? (“there are more X than you imagine, and even more of what you would call partially-X or X-lite”)

Lacking affective empathy is arguably one of the most defining characteristics of psychopathy, so I don’t think this is a good example.

Instead, think of all the peripheral things that people associate with psychopathy and that probably do correlate with it (and often serve as particularly salient examples or cause people to get “unmasked”), but may not always go together. Take those away.

For instance,

Sadism – you can have psychopaths who are no more sadistic than your average person. (Many may still act more sadistically on average because they don’t have prosocial emotions counterbalancing the low-grade sadistic impulses that you’d also find in lots of neurotypical people.)

Lack of conscientiousness and “parasitic lifestyle” – some psychopaths have self-control and may even be highly conscientious. See the claims about how, in high-earning professions that reward ruthlessness (e.g., banking, some types of law, some types of management), a surprisingly high percentage of high-performers have psychopathic traits.

Disinterested in altruism of any sort – some psychopaths may be genuinely into EA but may be tempted to implement it more SBF-style. (See also my comment here.)

Obsessed with social standing/power/interpersonal competition. Some may focus on excelling at a non-social hobby (“competition with nature”) that provides excitement that would otherwise be missing in an emotionally dulled life (something about “shallow emotions” is IMO another central characteristic of psychopathy, though there’s probably more specificity to it). E.g., I wouldn’t be shocked if the free-solo climber Alex Honnold were on some kind of “psychopathy spectrum,” but I might be wrong (and if he was, I’d still remain a fan). I’m only speculating based on things like “they measured his amygdala/-activation and it was super small.”

I definitely read all examples as “both at the same time.”

1) Whatever X publicly condemned thing you can think of, it exists on a spectrum.

2) There is a lot more of all instances of it happening than you think there are.

3) A lot of it does not look like the kind you are most likely to notice and condemn.

I agree. Let me elaborate, hopefully clarifying the post to Viliam (and others).

Regarding the basics of rationality, there’s this cluster of concepts that includes “think in distributions, not binary categories”, “Distributions Are Wide, wider than you think”, selection effects, unrepresentative data, filter bubbles and so on. This cluster is clearly present in the essay. (There are other such clusters present as well—perhaps something about incentive structures? - but I can’t name them as well.)

Hence, my reaction reading this essay was “Wow, what a sick combo!”

You have these dozens of basic concepts, then you combine them in the right way, and bam, you get Social Dark Matter.

Sure, yes, really the thing here is many smaller things in disguise—but those smaller basic things are not the point. The point is the combination!

This passage is from Terence Tao, describing his experiences reading a paper by Jean Bourgain, but it fits my experience reading this essay as well.

I am not sure if it’s the motivated reasoning speaking but I have a feeling that

if a distribution has 2 or more peaks it is customary to delineate in the valleys and have different words to indicate data points close to each peak [i.e. cleave reality at the joints] [e.g. autism]

If a distribution only has 1 peak, then you would have words for [right of peak] and [left of peak] and maybe [normal (stuff around the peak)] [e.g. height]

If I understand correctly Duncan is saying that the current word definition cleaving using the above rules in certain cases adheres to a false distribution leading to false beliefs.

Without having empirical data to back this claim, my guess would be that the autism distribution has a single peak at “no symptoms”. that is, the majority of the population has no symptoms, there are lots of people with mild symptoms, and the severe symptoms are down in the tail of the distribution.

I would not guess this. I would guess instead that the majority of the population has a few “symptoms”. Probably we’re in a moderate dimensional space, e.g. 12, and there is a large cluster of people near one end of all 12 spectrums (no/few symptoms), and another, smaller cluster near the other end of all 12 spectrums (many/severe symptoms) but even though we see those two clusters it’s far more common to see “0% on 10, 20% on 1, 80% on 1″ than “0% on all”. See curse of dimensionality, probability concentrating in a shell around the individual dimension modes, etc.

research found the autism distribution to mathematically have 2-5 peaks if I am parsing the study correctly with 1 corresponding to normal population and the other peaks gathered to the right

the study I found

https://molecularautism.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13229-019-0275-3

I have not read it in depth, just skimming. [no energy to actually give it the attention]

but the relevant image seems to be this:

so it seems to me that it is bi-modal, but not in the sense of male-female bi-modal. and it can mostly be simplified as a slightly skewed bell curve.

You tried to embed a hotlinked image from your gmail, which doesn’t display. You want to download it and then upload it to our editor.

There is social pressure to hide X. So, X turns out to be much more common and much less extreme than one naively imagined. The net effect is already out there, so maybe just chill.

But, the above story exists in equilibrium with the reverse reaction: