We need a field of Reward Function Design

(Brief pitch for a general audience, based on a 5-minute talk I gave.)

Let’s talk about Reinforcement Learning (RL) agents as a possible path to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

My research focuses on “RL agents”, broadly construed. These were big in the 2010s—they made the news for learning to play Atari games, and Go, at superhuman level. Then LLMs came along in the 2020s, and everyone kinda forgot that RL agents existed. But I’m part of a small group of researchers who still thinks that the field will pivot back to RL agents, one of these days. (Others in this category include Yann LeCun and Rich Sutton & David Silver.)

Why do I think that? Well, LLMs are very impressive, but we don’t have AGI (artificial general intelligence) yet—not as I use the term. Humans can found and run companies, LLMs can’t. If you want a human to drive a car, you take an off-the-shelf human brain, the same human brain that was designed 100,000 years before cars existed, and give it minimal instructions and a week to mess around, and now they’re driving the car. If you want an AI to drive a car, it’s … not that.

Teaching a human to drive a car / teleoperate a robot: Minimal instruction, | Teaching an AI to drive a car / teleoperate a robot: Dozens of experts, 15 years, $5,000,000,000 |

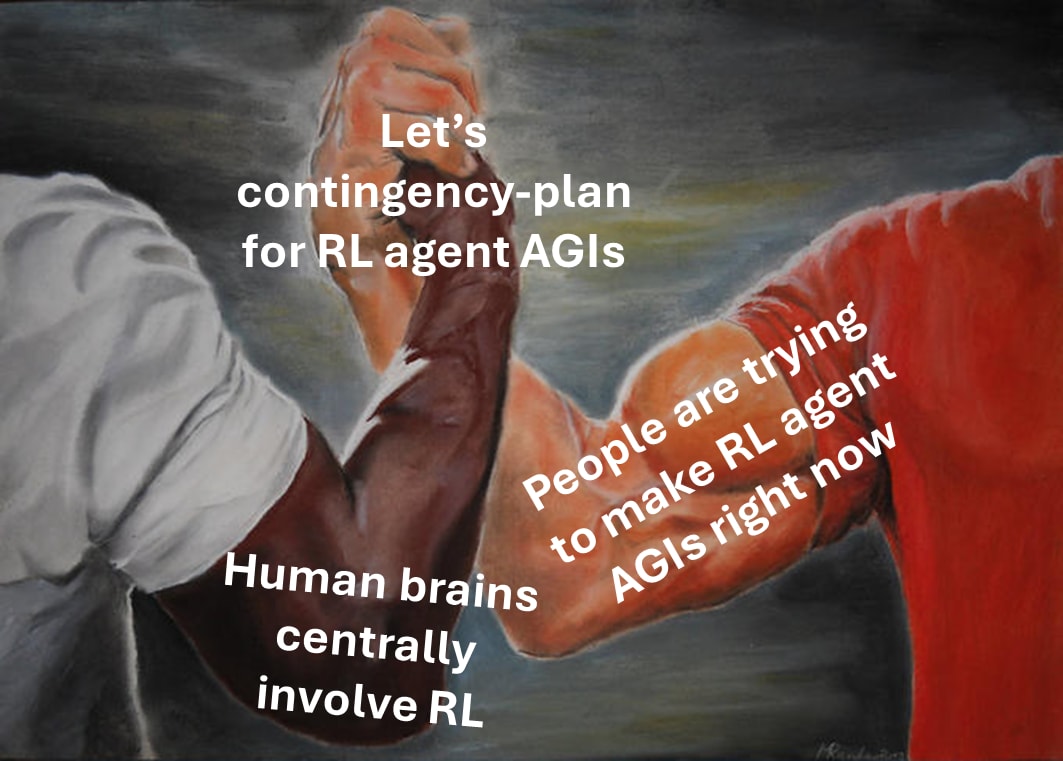

Anyway, human brains are the only known example of “general intelligence”, and they are “RL agents” in the relevant sense (more on which below). Additionally, as mentioned above, people are working in this direction as we speak. So, seems like there’s plenty of reason to take RL agents seriously.

So the upshot is: we should contingency-plan for real RL agent AGIs—for better or worse.

Reward functions in RL

If we’re talking about RL agents, then we need to talk about reward functions. Reward functions are a tiny part of the source code, with a massive influence on what the AI winds up doing.

For example, take an RL agent like AlphaZero, and give it a reward of +1 for winning at a board game and –1 for losing. As you train it, it will get better and better at winning. Alternatively, give it a reward of –1 for winning and +1 for losing. It will get better and better at losing. So if the former winds up superhuman at Reversi / Othello, then the latter would wind up superhuman at “Anti-Reversi”—an entirely different game! Again, tiny code change, wildly different eventual behavior.

I claim that if you give a powerful RL agent AGI the wrong reward function, then it winds up with callous indifference to whether people live or die, including its own programmers and users.

But what’s the right reward function? No one knows. It’s an open question.

Why is that such a hard problem? It’s a long story, but just as one hint, try comparing:

“negative reward for lying”, versus

“negative reward for getting caught lying”.

The first one seems like a good idea. The second one seems like a bad idea. But these are actually the same thing, because obviously the reward function will only trigger if the AI gets caught.

As it turns out, if you pick up a 300-page RL textbook, you’ll probably find that it spends a few paragraphs on what the reward function should be, while the other 299½ pages are ultimately about how to maximize that reward function—how do the reward signals update the trained model, how the trained model is queried, and sometimes there’s also predictive learning, etc.

Reward functions in neuroscience

…And it turns out that there’s a similar imbalance in neuroscience:

The human brain also has an RL reward function. It’s sometimes referred to as “innate drives”, “primary rewards”, “primary punishers”, etc.—things like ‘pain is bad’ and ‘eating when you’re hungry is good’. And just like in RL, the overwhelming majority of effort in AI-adjacent neuroscience concerns how the reward function updates the trained models, and other sorts of trained model updates, and how the trained models are queried, and so on. This part involves the cortex, basal ganglia, and other brain areas. Meanwhile, approximately nobody in NeuroAI cares about the reward function itself, which mainly involves the hypothalamus and brainstem.

We need a (far more robust) field of “reward function design”

So here’s the upshot: let’s learn from biology, let’s innovate in AI, let’s focus on AI Alignment, and maybe we can get into this Venn diagram intersection, where we can make headway on the question of what kind of reward function would lead to an AGI that intrinsically cares about our welfare. As opposed to callous sociopath AGI. (Or if no such reward function exists, then that would also be good to know!)

Oh man, are we dropping this ball

You might hope that the people working most furiously to make RL agent AGI—and claiming that they’ll get there in as little as 10 or 20 years—are thinking very hard about this reward function question.

Nope!

For example, see:

“The Era of Experience” has an unsolved technical alignment problem (2025), where I discuss a cursory and flawed analysis of reward functions by David Silver & Rich Sutton;

LeCun’s “A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence” has an unsolved technical alignment problem (2023), where I discuss a cursory and flawed analysis of (related) “intrinsic cost modules” by Yann LeCun

Book review: “A Thousand Brains” (2021), where I discuss a cursory and flawed analysis of the (related) “old brain” by Jeff Hawkins

…And those are good ones, by the standards of this field! Their proposals are fundamentally doomed, but at least it occurred to them to have a proposal at all. So hats off to them—because most researchers in RL and NeuroAI don’t even get that far.

Let’s all try to do better! Going back to that Venn diagram above…

Reward Function Design: Neuroscience research directions

For the “reward functions in biology” part, a key observation is that the human brain reward function leads to compassion, norm-following, and so on—at least, sometimes. How does that work?

If we can answer that question, it might be a jumping-off point for AGI reward functions.

I worked on this neuroscience problem for years, and wound up with some hypotheses. See Neuroscience of human social instincts: a sketch for where I’m at. But it needs much more work, especially connectomic and other experimental data to ground the armchair hypothesizing.

Reward Function Design: AI research directions

Meanwhile on the AI side, there’s been some good work clarifying the problem—for example people talk about inner and outer misalignment and so on—but there’s no good solution. I think we need new ideas. I think people are thinking too narrowly about what reward functions can even look like.

For a snapshot of my own latest thinking on that topic, see my companion post Reward Function Design: a starter pack.

Bigger picture

To close out, here’s the bigger picture as I see it.

Aligning “RL agent AGI” is different from (and much harder than) aligning the LLMs of today. And the failures will be more like “SkyNet” from Terminator, than like “jailbreaks”. (See Foom & Doom 2: Technical alignment is hard.)

…But people are trying to make those agents anyway.

We can understand why they’d want to do that. Imagine unlimited copies of Jeff Bezos for $1/hour. You tell one of them to go write a business plan, and found and grow and run a new company, and it goes and does it, very successfully. Then tell the next one, and the next one. This is a quadrillion-dollar proposition. So that’s what people want.

But instead of “Jeff Bezos for $1/hour”, I claim that what they’re gonna get is “a recipe for summoning demons”.

Unless, of course, we solve the alignment problem!

I think things will snowball very quickly, so we need advanced planning. (See Foom & Doom 1.) Building this field of “Reward Function Design” is an essential piece of that puzzle, but there are a great many other things that could go wrong too. We have our work cut out.

It seems likely to me that “driving a car” used as a core example actually took something like billions of person-years including tens of millions of fatalities to get to the stage that it is today.

Some specific human, after being raised for more than a dozen years in a social background that includes frequent exposure to car-driving behaviour both in person and in media, is already somewhat primed to learn how to safely drive a vehicle designed for human use within a system of road rules and infrastructure customized over more than a century to human skills, sensory modalities, and background culture. All the vehicles, roads, markings, signs, and rules have been designed and redesigned so that humans aren’t as terrible at learning how to navigate them as they were in the first few decades.

Many early operators of motor vehicles (adult, experienced humans) frequently did things that were frankly insane by modern standards and would send an AI driving research division back to redesign if their software did such things even once.

I agree with this, and I’d split your point into three separate factors.

The “30 hours to learn to drive” comparison hides at least:

(1) Pretraining: evolutionary pretraining of our visual/motor systems plus years of everyday world experience;

(2) Environment/institution design: a car/road ecosystem (infrastructure, norms, licensing) that has been iteratively redesigned for human drivers;

(3) Reward functions: they do matter for sample efficiency, but in this case they don’t seem to be the main driver of the gap.

Remove (1) and (2) and the picture changes: a blind person can’t realistically learn to drive safely in the current environment, and a new immigrant who speaks no English can’t pass the UK driving theory test without first learning English or Welsh, because of language policy, not because their brain’s reward function is worse.

A large part of the sample-efficiency gap here seems to be about pretraining and environment/institution design, rather than about humans having magically “better reward functions” inside a tabula-rasa learner.

Can I ask you to unwind the fundamentals a step further, and say why you and neuroscientists in general believe the brain operates by RL and has a reward function? And how far down the scale of life these have been found?

Oh, it’s definitely controversial—as I always say, there is never a neuroscience consensus. My sense is that a lot of the controversy is about how broadly to define “reinforcement learning”.

If you use a narrow definition like “RL is exactly those algorithms that are on arxiv cs.AI right now with an RL label”, then the brain is not RL.

If you use a broad definition like “RL is anything with properties like Thorndike’s law of effect”, then, well, remember that “reinforcement learning” was a psychology term long before it was an AI term!

If it helps, I was arguing about this with a neuroscientist friend (Eli Sennesh) earlier this year, and wrote the following summary (not necessarily endorsed by Eli) afterwards in my notes:

…But Eli is just one guy, I think there are probably dozens of other schools-of-thought with their own sets of complaints or takes on “RL”.

I don’t view this as particularly relevant to understanding human brains, intelligence, or AGI, but since you asked, if we define RL in the broad (psych-literature) sense, then here’s a relevant book excerpt:

I agree. And I think the same point applies to alignment work on LLM AGI. Even though it’s used for alignment and we expect more of it, there’s not what I’d call a field of reward function design. Most alignment work on LLMs is probing how the few RL alignment attempts work, rather than using different RL functions and seeing what they do. And it doesn’t even seem there’s much theorizing about how alternate reward functions might change current or future more capable LLMs’ alignment.

I think this analogy is pretty strong, and many of the questions are the same, even though the sources of RL signals are pretty different. The reward function for RL on LLMs seems to be more complex. It uses specs or Anthropic’s constitution, and now perhaps the much richer Claude 4.5 Opus’ Soul Document, all as interpreted by another LLM to produce an RL signal. But more RL-agent and brainlike RL functions are pretty complex too, since they’re nontrivial as hardwired, then expressed through a complex environment and a critic/value function that learns a lot. I think there’s a lot of similarity in the questions involved.

So I think your RL training signal starter pack is pretty relevant to LLM AGI alignment theory, too. It’s nice to have those all in one place and some connections drawn out. I hope to comment over there after thinking it through a little more.

And this seems pretty important for LLMs even though they have lots of pretraining which changes the effect of RL dramatically. RL (and cheap knockoff imitations like DPO) is playing an increasingly large role in training recent LLMs. A lot of folks expect it to be critical for further progress on agentic capabilities. I expect something slightly different, self-directed continuous learning, but that would still have a lot of similarities even if it’s not implemented literally as RL.

And RL has arguably always played a large role in LLM alignment. I know you attributed most of LLMs’ alignment to their supervised training magically transmuting observations into behavior. But I think pretraining transmutes observations into potential behavior, and RL posttraining selects which behavior you get, doing the bulk of the alignment work. RL is sort of selecting goals from learned knowledge as Evan Hubinger pointed out on that post.

But more accurately, it’s selecting behavior, and any goals or values are only sort of weakly implicit in that behavior. That’s an important distinction. There’s a lot of that in humans, too, although goals and values are also pursued through more explicit predictions and value function/critic reward estimates.

I’m not sure if it matters for these purposes, but I think the brain is also doing a lot of supervised, predictive learning, and the RL operates on top of that. But the RL also drives behavior and attention, which directs the predictive learning, so it’s a different interaction than the LLMs pretraining-then-RL-to-select-behaviors.

In all, I think LLM descendents will have several relevant similarities to brainlike systems. Which is mostly a bad thing, since the complexities of online RL learning get even more involved in their alignment.