It is easier to ask than to answer.

That’s my whole point.

It is much cheaper to ask questions than answer them so beware of situations where it is implied that asking and answering are equal.

Here are some examples:

Let’s say there is a maths game. I get a minute to ask questions. You get a minute to answer them. If you answer them all correctly, you win, if not, I do. Who will win?

Preregister your answer.

Okay, let’s try. These questions took me roughly a minute to come up with.

What’s 56,789 * 45,387?

What’s the integral from −6 to 5π of sin(x cos^2(x))/tan(x^9) dx?

What’s the prime factorisation of 91435293173907507525437560876902107167279548147799415693153?

Good luck. If I understand correctly, that last one’s gonna take you at least an hour1 (or however long it takes to threaten me).

Perhaps you hate maths. Let’s do word problems then.

Define the following words “antidisestablishmentarianism”, “equatorial”, “sanguine”, “sanguinary”, “escapology”, “eschatology”, “antideluvian”, “cripuscular”, “red”, “meter”, all the meanings of “do”, and “fish”.

I don’t think anyone could do this without assistance. I tried it with Claude, which plausibly still failed2 the “fish” question, though we’ll return to that.

I could do this for almost anything:

Questions on any topic

Certain types of procedural puzzles

Asking for complicated explanations (we’ll revisit later)

Forecasting questions

This is the centre of my argument

I see many situations where questions and answers are treated as symmetric. This is rarely the case. Instead, it is much more expensive to answer than to ask.

Let’s try and find some counter examples. A calculator can solve allowable questions faster than you can type them in. A dictionary can provide allowable definitions faster than you can look them up. An LLM can sometimes answer some types of questions more cheaply in terms of inference costs than your time was worth in coming up with them.

But then I just have to ask different questions. Calculators and dictionaries are often limited. And even the best calculation programs can’t solve prime factorisation questions more cheaply than I can write them. Likewise I could create LLM prompts that are very expensive for the best LLMs to answer well, eg “write a 10,000 word story about an [animal] who experiences [emotion] in a [location].”

How this plays out

Let’s go back to our game.

Imagine you are sitting around and I turn up and demand to play the “answering game”. Perhaps I reference on your reputation. You call yourself a ‘person who knows things’, surely you can answer my questions? No? Are you a coward? Looks like you are wrong!

And now you either have to spend your time answering or suffer some kind of social cost and allow me to say “I asked him questions but he never answered”. And whatever happens, you are distracted from what you were doing. Whether you were setting up an organisation or making a speech or just trying to have a nice day, now you have to focus on me. That’s costly.

This seems like a common bad feature of discourse—someone asking questions cheaply and implying that the person answering them (or who is unable to) should do so just as cheaply and so it is fair. Here are some examples of this:

Internet debates are weaponised cheap questions. Whoever speaks first in many debates often gets to frame the discussion and ask a load of questions and then when inevitably they aren’t answered, the implication is that the first speaker is right3. I don’t follow American school debate closely, but I sense it is even more of this, with people literally learning to speak faster so their opponents can’t process their points quickly enough to respond to them.

Emails. Normally they exist within a framework of friends or colleagues, who understand when emails should be sent and feel obliged to respond. But at some point often emails get too cheap—anyone can send you one and those norms change or your email becomes unusable. I don’t want everyone in the world to be able to ask me any question they want, it’s too cheap.

Freedom Of Information requests. I worked in Government for a while and anyone can ask for any information from any department. What follows is several days of a government employee’s time, either finding all the relevant documents and redacting them or giving a reason why the request is to be denied. Maddeningly, it’s also possible to send a ‘Freedom Of Information Meta-Request’, which then requires all documents about the original request. The costs are huge and all from a single email.

Further examples include political interviews, nagging questions on social media, support boxes on websites (and why they slowly fall in quality).

In all these cases, the system might work when there are established norms to limit the number or style of questions, but allowing anyone to ask these questions quickly becomes unbalanced.

Often when looking at norms of privacy or status, I ask myself “which cheap but generally acceptable interaction is being artificially limited4”. I prefer debates amongst groups who know and respect one another, giving time for longer answers. Between friends a question cannot be repeated for political effect. Email addresses are often hidden, or messaging is inside walled gardens, like Slack or Microsoft Teams. Companies do not give anyone the right to ask any question—comms departments often limit questions to employees.

Does anyone think otherwise?

Maybe this doesn’t sound like an insight, but it’s an observation I make relatively often and it explains for me why several of the above systems don’t work.

What I do personally

Notice this asymmetry. When I request information, it is often like I am charging the person perhaps somewhere between 10¢ and $100. Now they have to stop and decide whether to answer. Would I be happy to ask to borrow this much money from them? Would others endorse my asking? If not, perhaps I shouldn’t ask, even if the space allows it.

Before I ask it, I can think about whether it is a high priority—whether I would pay to know the answer, if more important than what they are currently doing. I might want to try again to find the answer myself—googling it or asking someone else.

I can think about ways to make the question easier to answer. Most emails can, in my experience, be framed as a set of yes/no questions. Shall I do X? Is $300 too much? If I am talking to a colleague I try to do the work so that my email is easy to answer. I really like these suggestions for making my emails more likely to be responded to.

I seek to mirror the amount of work the other person is doing. If I ask a question and someone responds in a clipped answer, I might not ask another. I dislike twitter users who respond to 1 tweet with 10. It is predictive that they don’t understand boundaries and turn-taking, which doesn’t bode well for future discussion.

How to fix this in systems

If a community or process lets anyone ask questions, I don’t expect it to work at scale.

If it does work there is often something going on to covertly reduce question numbers. I filled in a UK government consultation recently. Anyone could comment on the process, which sounds like an expensive thing to offer for free, unless it was to be ignored. But was about 100 questions long, with submission at the end. They’ll let anyone answer, but only if you are willing to put in the time to click through every box. So it becomes more expensive again.

Many systems have ways to make questions more expensive:

Limit question asking. On Twitter5, new private messages are sometimes limited to people you follow. You have made a choice to interact with someone before they can message you. This adds an additional price to questions.

Rebalance. It is normal in panel discussions for every question to have a 5 minute answer6. There is already the assumption that questions are hard to answer. Debates likewise could have systems where each debater takes the role of ‘asking questions and waiting for them to be answered’. If you just ask 50 hard questions you wast your time and it doesn’t look like you’ve got the upper hand.

Voting. Have unlimited questions but only answer the top ones according to some system. This works pretty well as long as those answering actually answer the top questions. In the Civil Service, during the departmental question time,, the top questions were usually about pay and were ignored. This damages trust in the whole process.

Make questions easier to answer. Stack Overflow is notorious for the rigid style of their questions and answers. I remember once someone removed ‘thank you’ from one of my replies, because Stack Overflow seeks to keep text as succinct as possible. I found that annoying at first, but over time, seeing the quality of replies I saw the benefit of only allowing very high quality messages in a certain format. Increasing the average question and answer makes the site a lot more useful.

Charge for it. Patreon allows people to interact with their favourite content creators, but often only if they pay the subscription. This provides good incentives for the content creator (who wants money) and for the user (who wants to talk to a high status person) and evens out the discrepancy between them. It’s much more appropriate to ask questions on a members’ area or a reddit AMA than if you see a celebrity in the street.

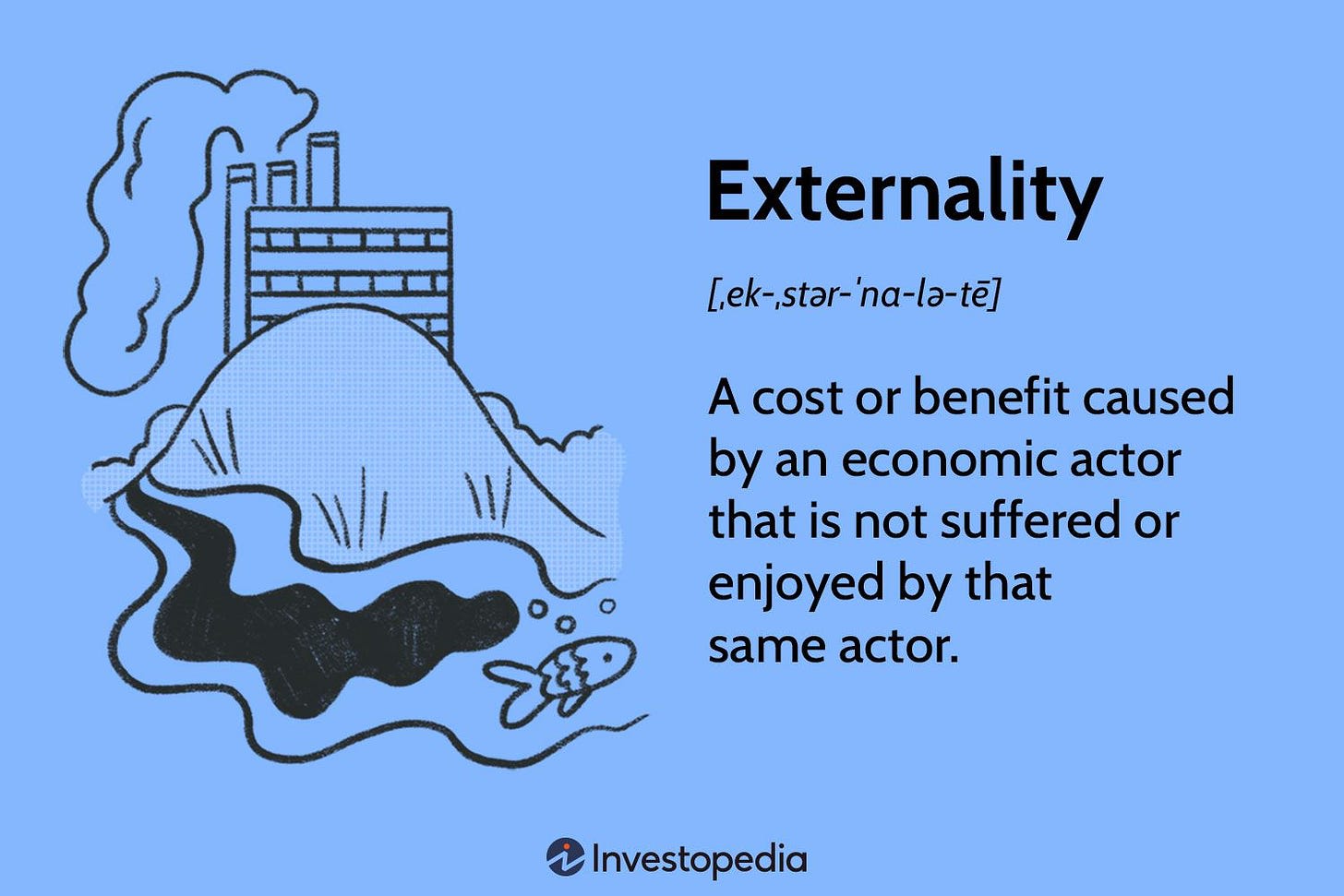

Is this an externality?

I sense cheap questions are an externality—when the costs of benefits of a transaction aren’t to those involved in the transaction. We have created a system where often questions—in debates, interviews, public interactions, social media—are free to ask, but this imposes costs on the answerer7. This leads to them being over-consumed for what is optimal for the system. Most of my solutions here are classic solutions to externalities (norms, regulation, restriction, taxation), so it seems likely it is one or is very close.

I recommend everyone learn what externalities are. It’s a concept that I think about perhaps once a week, in a very broad range of contexts. Here is a quick video

Conclusion: Questions are too cheap

If anyone can ask a free question, then anyone can ask 10 questions, or a question that is ten times as difficult to answer. Most systems cannot sustain this and in small groups we have norms to manage it. It is worth noticing how this breaks down at scale.

Both I and systems I am involved in can find ways to charge for questions, via membership, votes, consent or money, so that they are no longer too cheap.

That’s all folks! Any questions? How hard could they be?

I agree with your assertion that pure factual questions are cheaper and easier than (correct) answers. I fully disagree with the premise that they’re currently “too cheap”.

I see almost none. I see MANY situations where both are cheap, but even then answers are more useful and valued. I see others where finding the right questions is valued, but answering is even more so. And plenty where the answer isn’t available, but the thinking about how to get closer to an answer is valuable.

The examples you give all seem about social power and harassment, not really about questions and answers. They’re ABSOLUTELY not about questions and answers being symmetric, they’re explicitly about imposing costs on someone who feels obligated to answer. Fuck that. The solution is not to prevent the questions, but to remove the obligation to generate an expensive answer. Anyone’s free to ask any question, and most of the time they’ll be ignored, if they’re not providing some answers of their own.

I dunno, I feel like there’s often a reason that there’s considered to be obligations to generate answers. Like if someone pushes a claim on a topic with the justification that they’ve comprehensively studied the topic, you’d expect them to have a lot of knowledge, and thus be able to expand and clarify. And if someone pushes for a policy, you’d want that policy to be robust against foreseeable problems.

I can definitely see how there can be cases where there’s an unreasonable symmetry in how questions vs answers can be valued compared to how expensive they are, but it seems wrong to entirely throw out the obligation to generate answers in all cases.

Good suggestion.

Here’s an example of a cheap question I just asked on twitter. Maybe Richard Hanania will find it cheap to answer too, but part of the reason I asked it was because I expect him to find it difficult to answer.

If he can’t answer it, he will lose some status. That’s probably good—if his position in the OP is genuine and well-informed, he should be able to answer it. The question is sort of “calling his bluff”, checking that his implicitly promised reason actually exists.

Public discourse norms, especially in the twitter age, are funny. Hanania has a lot of options, none of which really change his status much.

he can ignore you. There’s enough volume that he doesn’t respond to most comments, so this isn’t him dodging a particularly harsh criticism, it’s just not worth his notice.

he can answer cheaply, by rephrasing (or just reposting) previous texts.

he can answer a different question that’s vaguely related.

Yeah I mean, I’m not claiming it has a big sense of obligation, only that it illustrates a condition where discourse seems to benefit from a sense of obligation.

This feels like a post that was likely motivated by one or more concrete instances where someone was asked a question and was expected to answer despite answering being expensive. Is that true? If so, are any of the original motivating instances public?

I think the motivating instances are largely:

Online debates are bad

Freedom Of Information requests suck

I think I probably backfilled from there.

I do sometimes get persistant questions on twitter, but I don’t think there is a single strong example.

I don’t have much experience with freedom of information requests, but I feel that when questions in online debates are hard to answer, it’s often because they implicitly highlight problems with the positions that have been forwarded. For all I know, it could work similarly with freedom of information requests.

Questions are not a problem, obligation to answer is a problem. Criticism is not a problem, implicit blame for ignoring it is a problem. Availability of many questions makes it easier to find one you want to answer.

Incidentally, understanding/verifying/getting-used-to/starting-to-track the answer (for those who care about the question) is often harder than writing an answer (for those whose mind was already prepared to generate it).

Though sometimes the obligation to answer is right, right? I guess maybe it’s that obligation works well at some scale, but then becomes bad at some larger scale. In a coversation, it’s fine, in a public debate, sometimes it seems to me that it doesn’t work.

Obligation to answer makes questions/criticism cause damage unrelated to their content, so they are marginally more withheld or suppressed. If they won’t be withheld or suppressed, like in a debate, they still act as motivation to avoid getting into that situation. The cost has a use for signaling that you can easily provide answers, but it’s still a cost, higher for those who can’t easily provide answers or don’t value conveying that particular signal.

I think if any interaction becomes cheap enough, it can be a problem.

Let’s say I want to respond to ~ 5 to 10 high-effort questions (questions where the askers have done background research and spend some time checking their wording so it’s easy to understand), and I receive 8 high-effort questions and 4 low-effort questions, then that’s fine- it’s not hard to read them all and determine which ones I want to respond to.

But what about if I receive 10 high-effort questions, and 1000 low-effort questions? then the low-effort questions are imposing a significant cost on me, purely because I have to spend effort to filter them out to reach the ones I want to respond to.

My desire to participate in answering questions, coupled with an incredibly cheap question-asking process, is sufficient to impose high costs on me (if I set up some kind of automated spam filter, this is also a cost, and leads to the kind of spam filter/automated email arms race that we currently see, with each automated system trying to outsmart the other).

Generally: in maneuver warfare you seek to make your opponent spend more energy per unit of reaction/movement than you do, wearing them down or putting them in a position of weakness.

Justify this extensively right now or you’re a phony

Replying to this because it seems a useful addition to the thread; assuming OP already knows this (and more).

1.) And none of the correct counterplays are ‘look, my opponent is cheating/look, this game is unfair’. (Scrub mindset)

2.) You know what’s more impressive than winning a fair fight? Winning an unfair one. While not always an option, and usually with high risk:reward, beating an opponent who has an assymetric situational advantage is hella convincing; it affords a much higher ceiling (relative to a ‘fair’ game) to demonstrate just how much better than your opponent you are.

I think a significant contributing factor that makes ‘simple’ questions in some contexts prohibitively difficult to answer is the lack of True Availability of the information being requested.

In this case, I’m defining True Availability[1] as the requested content being already prepared and organized into the correct format and grouped together, needing no further processing other than finding it. Conditional Availability would be when you know how to obtain the information, but it requires some degree of processing and filtering to be ready for consumption.

In computer science, this is similar to a lookup table. Lookup tables typically contain a collection of pre-calculated results for common computations, because looking up a result in a table is generally faster than calculating it from scratch.

Anything you have in a LT is Truly Available, whereas anything you have to calculate is Conditionally Available.

In your example of freedom of information requests, the questions are hard to answer because they are only available on the condition that someone filters the requested information from everything else and then prepares it into a usable format for releasing.

If I was tasked with refining the information availability of a large organization, I would attempt to prepare publicly-releasable copies of everything that COULD legally be requested via freedom of information act and publish a public database of that. Let them knock themselves out. Individual request processing and answering sounds like a terribly inefficient method of sharing information.

There are probably legal/bureaucratic/practical difficulties to my proposed solution, but my point is merely that there are in some contexts systemic barriers making answers disproportionately expensive rather than answers being intrinsically more difficult in every case.

I suspect there already exist more conventional terms for the concepts I’m referring to, but I’m making do with what I already have Available.

109647247078573083699910710287 × 833904139046784164224502687119

With the right tool, it takes about 12 seconds. 5 to locate the tool, 7 for it to give the answer.

Just nitpicking, of course. You could have easily taken 60-digit primes.

Sadly you are the second person to correct me on this @Paul Crowley was first. Ooops.